Southeast Asia, especially member states of The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), are expected to undergo a digital transformation over the coming years which would drastically change the lives of its citizenry. Global management consulting firm, A.T. Kearney predicts that the pursuit of a radical digital agenda could potentially add US$1 trillion to the region’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in the next decade.

With this paradigm shift, comes a surge in the demand for energy. The advent of data centres, cloud storage facilities and the building of new infrastructures to undergird these technological advances would require sufficient access to energy and power. As the region attempts to feed its growing thirst for power, it can use technology more effectively to improve the energy sector as a whole.

Doing so will require the harnessing of blockchain technology that has recently proven to hold a myriad of potential uses in our lives.

The Asian Development Bank (ADB) surmises the potential of blockchain in the energy sector in five D’s – decentralised, democratised, deregulated, distributed and digitalised.

At the crux of blockchain technology is its decentralised nature based on a distributed network structure as opposed to a centralised one. Essentially, the technology is a digital, publicly distributed ledger of records which is open to inspection by every participant while not being subject to any form of central control.

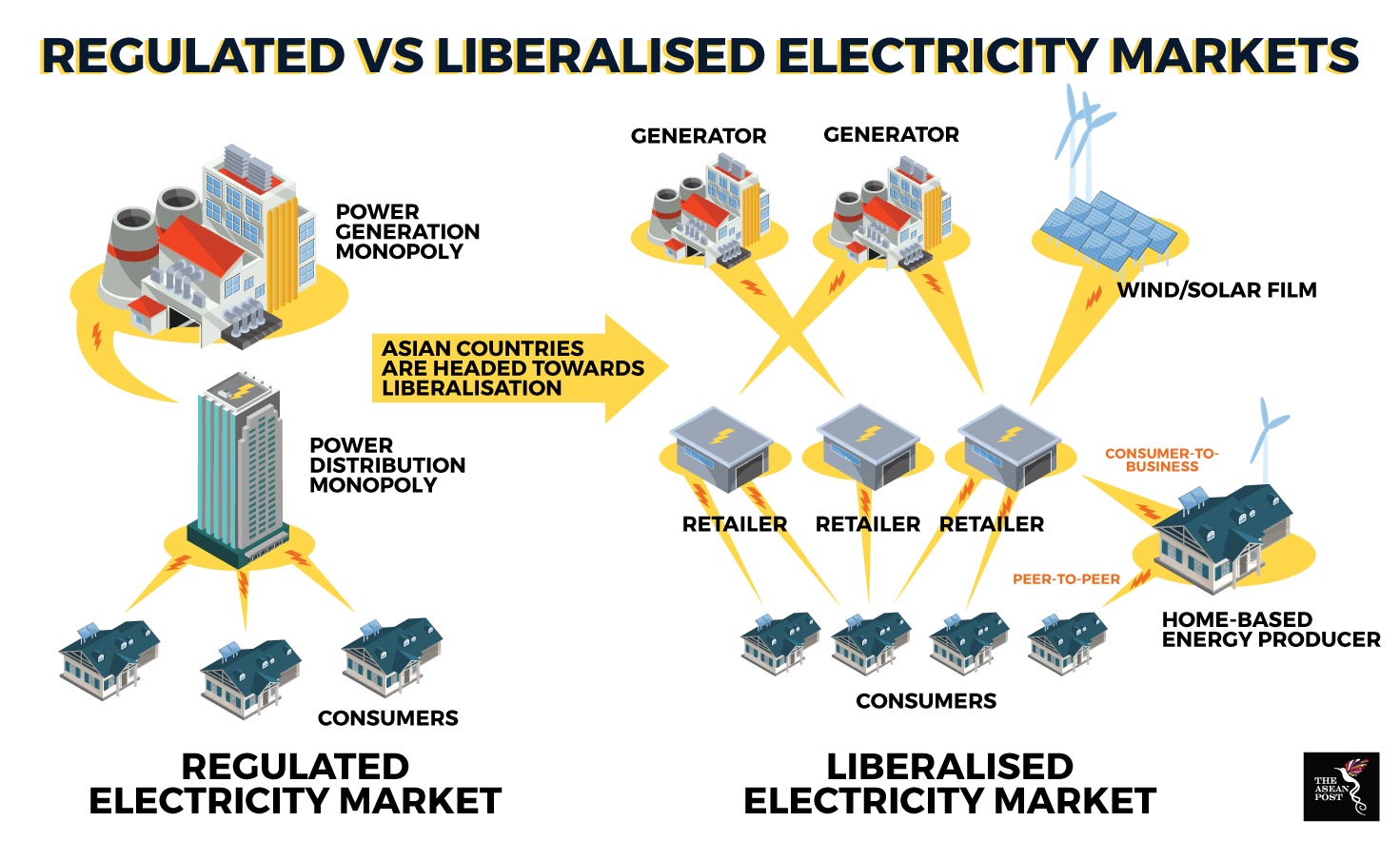

The current energy architecture in most parts of the world is one where there is a power producer who distributes power to customers at a particular rate. This rate is affected by the energy supply chain which often involved intermediaries like utility companies and banks which add to the cost of electricity which is then levied to customers.

However, with blockchain, this system can be replaced with a distributed model where anyone within the energy architecture could produce and buy energy from one another in a peer-to-peer energy market, hence eliminating any third party from the picture. For example, if an individual has a solar array in his/her backyard, it could be used to power the entire household and the excess electricity generated could then be fed back into the grid. This surplus electricity can be purchased by another household which isn’t producing electricity on its own or is running on an energy deficit.

A peer-to-peer market cannot be sustained by household electricity suppliers alone. It will need electricity retailers which can guarantee reliable and adequate electricity supply to end users. Because of the decentralised nature of the distributed energy system, such retailers can easily be part of this liberal energy market.

Source: Various sources

Buyers and sellers will be governed by a “smart contract” which is also rooted in blockchain architecture. The system would record the transaction history taking place in the peer-to-peer structure into a tamper proof ledger, thus enabling payments to be made without the need for a middleman like a bank which will only drive costs higher.

Such a system opens up new avenues for energy retailers to profit from the liberalisation of the electricity market. However, buyers and sellers beware, technology is often always a double-edged sword.

While blockchain does not have a single point of failure which makes hacking it incredibly difficult, it is still not completely impervious to cyberattacks. The delivery of the technology to end users requires software which is written by humans and whenever there is a human element involved, there are associated risks.

In May 2016, hackers exploited a loophole in the smart contract code of the Decentralized Autonomous Organization (DAO), leading to a loss of approximately US$60 million. In the same year, the world’s largest Bitcoin exchange, Bitfinex fell victim to a security breach resulting in a US$60 million loss as well. The following year, it suffered a distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attack; while not resulting in a major financial loss, the attack raised questions about the security of systems based on blockchain technology.

Computer scientists are hard at work trying to make the technology more transparent, safer and reliable for everyday use. As with any technology, the faster it evolves, so too will the minds of blackhat hackers looking to exploit it for their own reprehensible reasons. The trick is to stay one step ahead of them. Only then, can the technology be fully harnessed; not only in the energy sector but across all sectors as well.