Public transparency and accountability are cornerstones of a citizen-centric approach to governance, and while ASEAN countries show some signs of having transparent processes in place, challenges still exist.

A citizen-centric approach is one where instead of the bureaucracy second-guessing citizens, they are consulted about their needs and encouraged to participate in policy planning, service designs and deliveries.

According to a joint report published this week by the Asian Development Bank (ADB) and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), ASEAN governments are strengthening their governance structures and institutional capacity to deliver better services to their people in the pursuit of a citizen-centric approach.

The report titled ‘Government at a glance: Southeast Asia 2019’ provides internationally comparable data on government resources, processes and outcomes on public governance in ASEAN member countries, covering 34 indicators in areas such as public services, digital government and transparency.

“Strengthening public institutional capacities is critical to all operations, and ADB remains committed to supporting our developing member countries in improving public sector management functions and financial stability while promoting more effective, timely, corruption-free and citizen-centric delivery of public services,” said Bambang Susantono, Vice-President for Knowledge Management and Sustainable Development at ADB.

Budget transparency

The civil service plays a key role in delivering public services and is the backbone of development in each ASEAN member state, and the Putrajaya Joint Declaration on ASEAN Post-2015 Priorities towards an ASEAN Citizen-Centric Civil Service – which was signed in 2015 by the 10 heads of civil service in ASEAN – is one of the steps the region has taken to promote citizen-centric governance.

As the ASEAN Secretariat notes, enhancing regional cooperation for effective, efficient, transparent and accountable civil service systems and good governance contributes to the achievement of the ASEAN Vision 2025 – a community that is politically cohesive, economically integrated, socially responsible, rules-based and people-oriented.

One crucial aspect of a people-oriented, citizen-centric approach is budget transparency – a key area in which parliament, citizens and non-government organisations can hold the government to account.

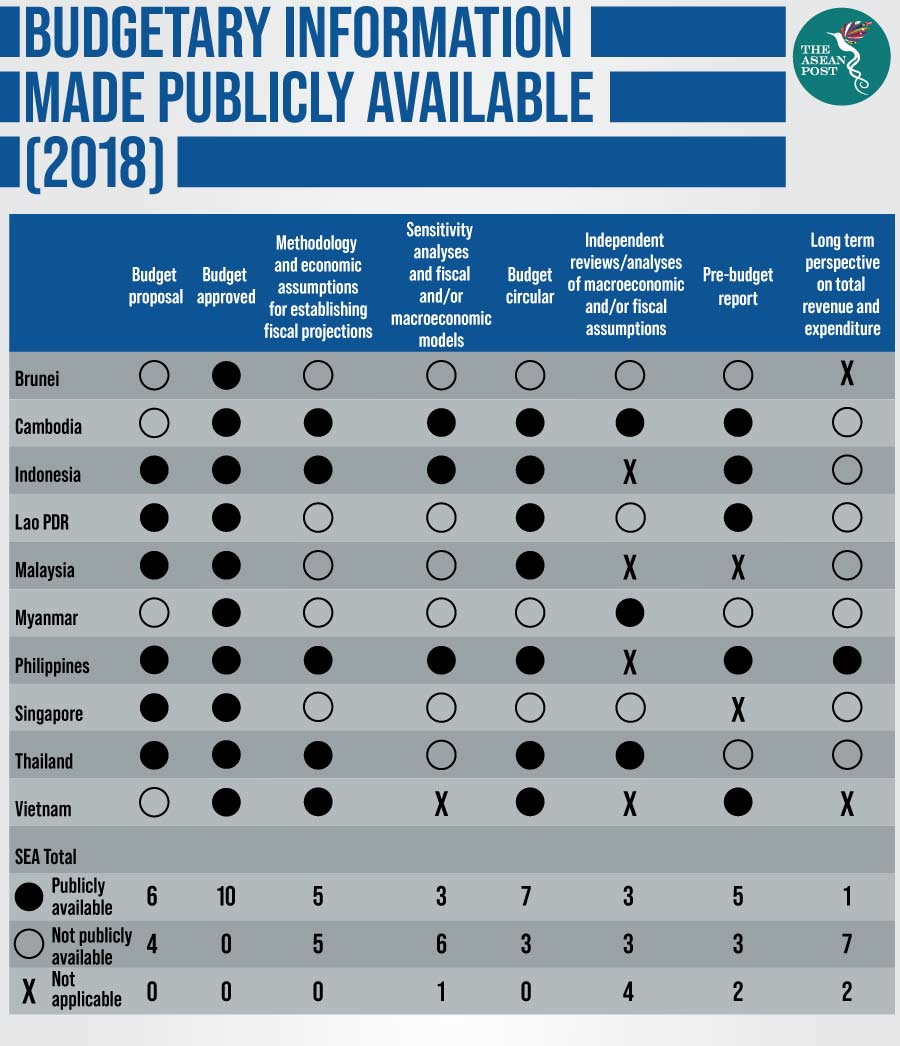

Being fully open with people about how public money is raised and used will go a long way in fostering citizens’ perception of government integrity, and while all ASEAN member nations make certain parts of their budget public, only half release the methodology and economic assumptions of the fiscal projections supporting their respective budget.

Even fewer currently publish sensitivity analyses, a common practice in most OECD countries.

While the majority of countries in the region publish citizens’ guides to the budget – explaining key information in plain language – and most produce long-term revenue and expenditure perspectives, only the Philippines makes this document publicly available, a stark contrast to OECD countries, where three-quarters do so.

‘I do not know exactly the reason’

But even in the Philippines there are some speedbumps.

Transparency advocates in the country questioned the funds for confidential and intelligence being requested by the Office of the President (OP) in the National Expenditure Program 2020 last month, which if approved, will be almost double that of President Rodrigo Duterte’s spending in previous years.

The US$43.3 million each for confidential and intelligence expenses is US$19.2 million higher than the US$24 million which the administration sought in 2017, 2018 and 2019. The US$24 million, in turn, was already heavily criticised by lawmakers and other stakeholders as it was more than four times the amount requested during the last year of the Benigno Aquino III administration (US$4.8 million).

Duterte’s spokesman, Salvador Panelo, was unable to provide further details as to the increase, telling Filipino media, “I do not know exactly the reason.”

Panelo said that based on “common sense,” the funds would be used to help “secure the nation.”

As Filipino media rightly reported, such confidential and intelligence funds raise red flags for transparency since the offices that spend them are not required to produce receipts or publicly disclose expenses due to their sensitive nature.

Data is key

Citizen-centric and data-driven processes require access to information as a basic pre-condition.

While “freedom of information” (FOI) laws create a framework of legal rights for citizens to request public sector information, only three countries in ASEAN – Indonesia, the Philippines and Vietnam – have such laws.

Promoting open government principles requires pro-active government dissemination of information, and as the ADB and OECD pointed out in the report, open government data that can be shared, analysed and reused on a large scale – within the framework of personal privacy and data protection legislation – offers new opportunities to empower citizens, businesses, civil society organisations, researchers and journalists.

As the World Economic Forum (WEF) notes, transparency in policy-making correlates positively with trust in politicians and negatively with the level of perceived undue influence.

In turn, an open and transparent policy-making process in ASEAN will help ensure that resources are used for designing and implementing policies that promote inclusive growth instead of exacerbating inequality.

Related articles:

Corruption: How is ASEAN performing?