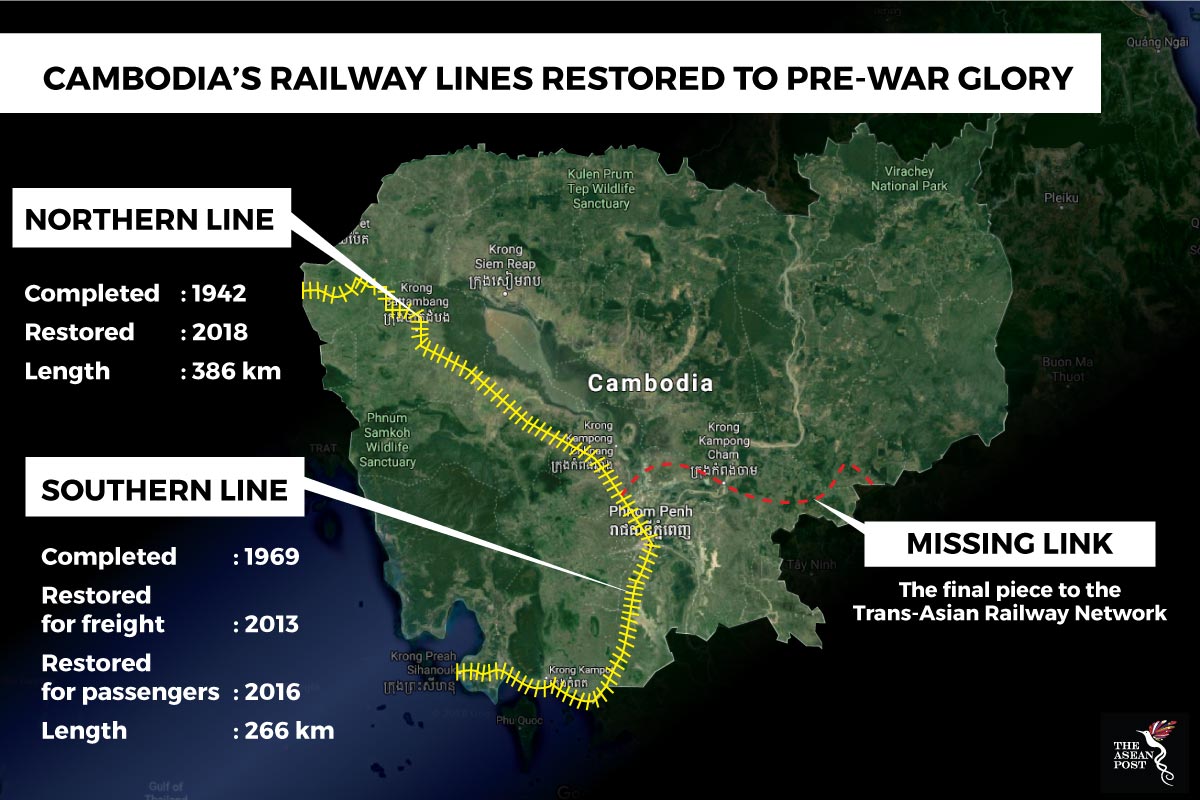

The recent completion of Cambodia’s railway from Phnom Penh to the border of Thailand has effectively restored the country’s rail network to pre-war conditions and added a missing link in the Trans-Asian Railway (TAR) network.

All that is required now is diplomacy. Ministerial level talks have started between Cambodia and Thailand to reconnect the towns of Poipet and Aranyaprahet, respectively.

“Passengers cannot cross the border by train yet because there are three points in our railway agreement that we still haven’t managed to agree upon,” said Sun Chanthol, Cambodia’s minister of public works and transportation. “Once the agreement is signed, Cambodians will be able to take the train from Poipet to Bangkok, and then in Thailand they can board a train all the way to Singapore.”

The Phnom-Penh-Poipet link represents a significant achievement. “From now on, passengers can travel by train from Phnom Penh to Poipet city for the first time in 45 years,” added Chanthol.

The Asian Development Bank (ADB) provided US$13 million in 2009 to rebuild the line. The minister added that the rail line will play a key role in facilitating trade and moving people between Cambodia and Thailand. Train fares are much cheaper than buses, he said, and trains can travel at an average speed of 40 km/h.

Another link in the TAR

There remains one more connection from the capital to Ho Chi Minh City, to complete the rail connection from Kunming in China to Singapore. Plans for this link are included in the Vietnam-Cambodia Cooperation Strategy in the Transport Sector (2015-2018). Both countries concluded negotiations on a memorandum of understanding in July 2017.

The idea of a railway connection between Asia and Europe is not new. In the 1950s, long before the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) came into being, several nations started a project to link Singapore to Istanbul and from there, to Europe and Africa. However, the Cold War and economic problems, among others, put a stop to this ambitious enterprise.

With the normalisation of relations between nations, the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (UNESCAP) kicked off the Asian Land Transport Infrastructure Development project in 1992 to build a transcontinental railway network between Europe and Pacific ports in China.

The Trans-Asian Railway Network Agreement was signed on 10 November, 2006 by 17 Asian nations. The “Iron Silk Road” formally came into force on 11 June, 2009.

Historic railways

The first of Cambodia’s two railway lines were built during the colonial French Indochina period. Construction on the 385 km Phnom Penh-Poipet railway line started in 1930. The Phnom Penh Railway Station opened in 1932 and the final link to Thailand was completed in 1942.

The 266 km Phnom Penh-Sihanoukville southern line was built in 1969 with financial assistance from France, then-West Germany and China. It was intended to help reduce Cambodia’s dependence on Vietnam and Thailand’s ports.

Sources: Various sources

Sources: Various sources

However, civil war which erupted in 1970 caused major destruction to the country’s infrastructure. The port in Sihanoukville was bombed by the United States (US) Air Force after the Khmer Rouge hijacked an American container ship. Tracts of the railway and road systems were destroyed during the five-year conflict. A 48 km section of the tracks near the border town of Poipet was destroyed in 1973.

The war and neglect also led to the deterioration of the railway links. Derailments were commonplace and the trains could travel no faster than 5 km/h. Earnings were low and by 2009, all rail services were suspended.

In their absence rose a new form of rail transport, the norry. Also known as the bamboo railway or flying carpets, the norries comprise bamboo platforms laid on two sets of steel wheels. A small engine is used to propel the platform and it can reach speeds of up to 40 km/h.

When two norries from opposite directions meet, the lighter norry has to yield. The driver and passengers have to alight, disassemble the vehicle to let the other norry pass, before reassembling their transport to continue on with their journey.

Rough roads

The bamboo railway is unsuitable for hauling large amounts of freight. Consequently, the existing road network became the main mode of transport. However, Cambodia suffers from a shortage of highways and high-quality roads. The Ministry of Public Works and Transport, reported that over half of the kingdom’s 6,000 km of roads are classified as “poor” or “bad” quality.

This may be attributed to limited funding. About 70 percent of Cambodia’s roads and bridges are funded by loans from China. “In Cambodia, more than 2,000 km of roads, seven river bridges and a new container terminal at Phnom Penh Autonomous Port have already been built under concessional loans from China,” explained Chanthol.

Since 2004, China has loaned out more than US$2 billion for road and bridge development, he added, with another four road and bridge projects underway.

China-funded roads are built by Chinese companies. They often use a low-cost method of laying down a thin bed of crushed stones, topping it off with rubberised asphalt. Such roads do not weather the rainy season well.

“Water can damage the foundations of roads,” said Thou Samnang, deputy director of the Heavy Equipment Centre at the Ministry of Public Works and Transport. “The government is spending a lot of time on road maintenance. Repairs are an important factor for sustainability.”

Cambodia’s roads also get damaged by overloaded vehicles – from trucks to motorcycles – packed with goods and passengers.

Better infrastructure, lower costs

Chanthol said the Cambodian government recognises the critical importance of a healthy, efficient and cost-effective national infrastructure to expedite trade and lower transportation costs overall. Trade moves through different modes of transport, by sea, river, airfreight, rail and road, and these respective networks will continue to be rehabilitated, built and expanded.

An efficient transport network and industry will attract foreign direct investment (FDI) which will lead to jobs creation and the improvement of Cambodians’ standard of living, he said. With better logistics, companies do not have to stockpile large inventories. Cambodia can become an attractive investment destination and a node in ASEAN’s production networks.

“If we manage to reduce supply chain bottlenecks by 50 percent, we would raise trade by 15 percent and production by five percent. The 2016 Logistics Performance Index of the World Bank has shown that Cambodia’s general performance has improved with the country moving from 83rd place in the 2014 rankings to 73rd place in 2016. Yet we can’t be satisfied with this ranking, as long as our main exports – garments and rice – still face competitive challenges due to high transportation costs,” he said.

Cambodia’s railway is expected to play an important role in moving cement, salt, rice for domestic consumption and export and sugar cane.

Rehabilitation work began in 2006 with funding from the ADB, Australian Agency for International Development (AusAID) and Toll Holdings from Australia. The latter was given a 30-year concession to reconstruct and operate the lines under Toll Royal Railways. However, Toll divested its 55 percent stake in the joint venture in December 2014 due to economic reasons, leaving the Royal Group to operate and redevelop the rail network.

The southern line to Sihanoukville Port was completed earlier and began hauling freight in 2013. Passenger services started in May 2016. Work on rehabilitating the northwest line began in 2015.

The Trans-Asian Railway Network and the BRI

The TAR was envisioned as a means to improve economies and accessibility of land-locked countries, such as Lao PDR, Afghanistan, Mongolia and Central Asia. Shipping and air travel was not as well developed then and rail was an economical way to transport commodities. TAR-related countries form the Eurasian land bridge, on which the BRI also plans to connect.

Southeast Asia’s rail systems are relatively easy to connect as they run on the 1,000 mm metre gauge – the distance between two rails – and trains can cross borders directly. When tracks of different gauges meet, the shipping containers must be moved from one train to another. India, Pakistan and Bangladesh use the wider 1,676 mm Indian gauge while the European Union (EU) and Russia use the 1,435 mm standard gauge.

High-speed rail lines in most parts of the world also use the standard gauge, making them incompatible with Southeast Asia’s rail lines. As the BRI advocates high speed rail connections, it disregards rather than leverages each country’s existing infrastructure.

In 2010, the China Railway Group and Cambodia Iron & Steel Mining Industry Group announced a joint venture to build a 405 km north-south line to connect a planned steel factory in the northern Preah Vihear province to a new port in Koh Kong province in the Gulf of Thailand. It will not connect to the Royal network. The project is stalled due to funding issues.

The BRI has brought new suitors to Cambodia. China’s CRRC Zelc declared last year it was conducting a feasibility study on investing in the country’s railway system and contributing to the initiative. Two years before that China Railway International Group also conducted a similar study.

With or without the BRI and its high-speed locomotives, the Trans-Asian Railway continues to trundle along as Cambodia and Vietnam contemplate the final missing link between Phnom Penh and Ho Chi Minh City. Though slower, the railway system will serve as an important low-cost way to boost Cambodia’s economy.

Tourism may even get a shot in the arm if the operator of the Eastern and Oriental Express decides to extend its luxury route from Singapore to Phnom Penh. That would certainly rival the allure of the Orient Express.