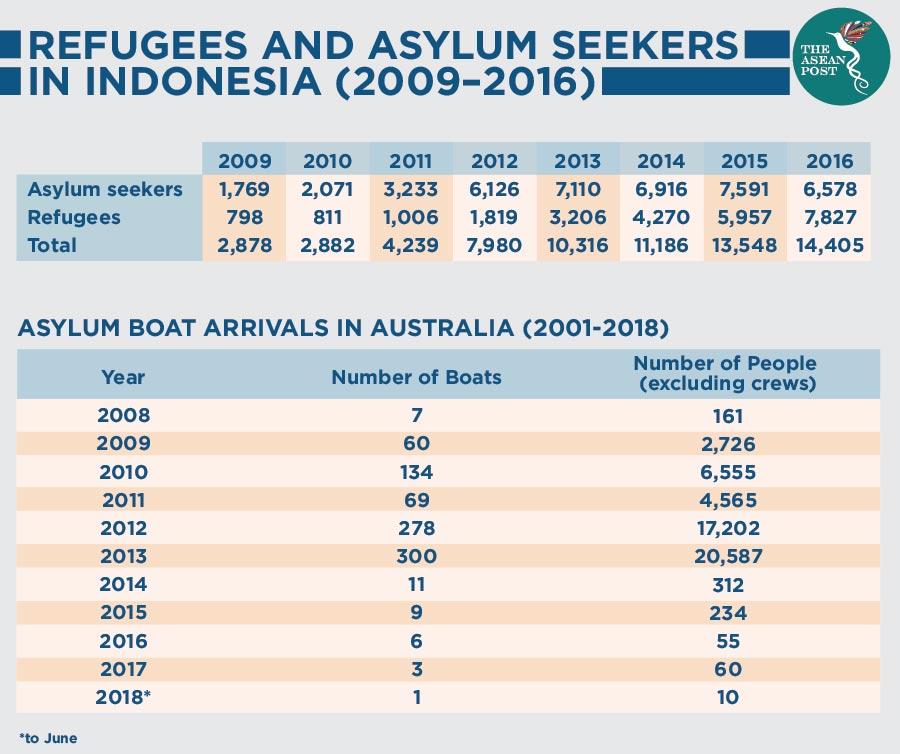

The Indonesian government has strong reason to draw policy lessons from the international community in order to deal with over 14,000 transiting refugees and asylum seekers, before the situation deteriorates further.

While the refugee issue is not a political priority in Indonesia, it seems to garner much traction for Australian politicians – where refugee issues dominate their agenda. Over the years, the Australian government has implemented an increasingly restrictive immigration policy. During its 2019 elections, there was major political debate on whether to maintain its offshore detention policy.

Indonesia’s geographical features makes it an easy entry point for asylum seekers who wish to go undetected. Aware of this, Australia has implemented policies such as the Pacific Solution and the Operation Sovereign Border policy to reduce the likelihood of asylum seekers eventually making their way to Australia.

Part of Australia’s efforts include large monetary contributions to Indonesia in order to address the needs of incoming refugees. Indonesia has received millions to fund various activities including the improvement of its border alert system (CEKAL), fully funding the International Organisation for Migration’s (IOM) Regional Cooperation Arrangement activities, and also the refurbishment costs of several immigration detention centres.

It is clear that Australia will not compromise on its efforts to end the irregular movement of asylum seekers between the two countries. Australia has effectively shifted the burden of transiting refugees to Indonesia, while wrapping it with generous financial aid programs.

However, support for this plan in Australia has been waning. This is evident in its policy changes. For example, Australia no longer supports the resettlement of refugees registered with the United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR) in Indonesia after 1 July, 2014. In addition, it has reduced its annual intake of refugees from Indonesia from 600 to 450 with the aim of deterring refugees from using Indonesia as a transit point before entering Australia.

In March 2018, the Australian government announced a reduction in its annual appropriation to support the IOM’s Regional Cooperation Arrangement activities with Indonesia on the grounds that it did not want the IOM’s care to be a deciding factor for international migrants to come to Indonesia.

Under this new arrangement, Australia still continues to fund the IOM in Indonesia to support the existing 9,000 refugees, but no longer supports migrants who arrived in Indonesia after 15 March, 2018. This has resulted in thousands of refugees living without support in Indonesia.

The Indonesian government needs to engage in a policy learning process in which it could take three practical steps as suggested by Prof Richard Rose, Director of the Centre for the Study of Public Policy at the University of Strathclyde, who introduced the concept of lesson-drawing in public policy.

First, Indonesian policymakers can look at the experience of other countries when handling the problem of refugees and asylum seekers in order to acquire knowledge and ideas about programmes that have been implemented.

Second, the Indonesian government needs to create a conceptual model of the implemented policy of each international example. The aim here is to show how and why the policies work in those countries in addition to their strengths and weaknesses. Third, a prospective evaluation is crucial by comparing the foreign models with the domestic refugee problem to fit the Indonesian context.

These steps will help the Indonesian government create a policy that accommodates its needs by transferring relevant effective approaches that have been taken by different countries.

While challenges in the lesson-drawing process is inevitable, Rose argues that for a policy programme in one political setting to be ideally feasible in another political setting, it requires two distinct judgements: practicality judged by policy experts (technical feasibility), and desirability appraised by elected politicians (political feasibility).

Studies have shown that political, bureaucratic, and economic resources constrain policy transfer. Furthermore, the cost of implementing new policy will be a major hurdle considering that the Indonesian government has explicitly stated that they are unwilling to spend money on refugee affairs. By allocating a budget for this purpose, they would risk losing voters’ support during the next elections.

Studies have further acknowledged that institutional and structural constraints will not allow governments to become involved in a policy transfer process. Indonesia’s unitary system of government, underpinned in its national motto, Bhinneka Tunggal Ika (unity in diversity) and in the national ideology, Pancasila (five principles), is a clear constraint on a policy transfer process.

For example, in May 2015, Aceh’s municipal government decided to enrol 225 Rohingya refugee children into the Indonesian primary and secondary schools, and encouraged a number of local social institutions to help the students by offering Indonesian and English lessons. This is an indication that the problem of refugees and asylum seekers in Indonesia can be better addressed by regional government rather than the central government. In addition, due to the existence of 12 Indonesian political parties espousing different ideologies, policy platforms, and leadership models, democratic decision-making can be a very slow and tedious process.

However, despite the aforementioned obstacles, the Indonesian government can still be involved in the policy transfer process by relying on suitable actors. A policy programme is likely to be adopted if it is deemed desirable by politicians and capable of transfer by policy experts. This condition can be achieved if the Indonesian government selects proper potential actors to assist in the policy transfer process even though the refugee and asylum seeker issue is not included in their political agenda. The actors include policy consultants, supranational organisations, and nongovernmental actors which can include think-tanks or research institutes, nongovernmental organisations, and interest groups.

Indonesia should learn from other countries to better handle transiting refugees and asylum seekers, despite the likelihood that challenges in a policy learning process may be encountered. Australia’s policy changes have clearly provoked dissatisfaction in Indonesia. In 2016, Indonesia’s Director-General of Immigration, Ronny Sompie, made an appeal to the Australian government to take more refugees from Indonesia – which he was noted as saying ‘you can’t afford not to’. In other words, when the conditions of uncertainty presented by policy changes arise, policymakers become more involved in wanting to do something to get rid of the dissatisfaction.

This policy challenge is more in Australia’s interests than Indonesia’s. Australia wants to prevent asylum seekers from reaching its territory, whereas Indonesia wants asylum seekers and refugees to leave the country. What would happen if diplomatic relations between the two nations deteriorates as a result of this issue? Today, Indonesia is simply not equipped or prepared to deal with its transiting refugees and asylum seekers.

Related articles: