Bitcoin cryptocurrency has been receiving some bad press in Asia recently because of the lack of a central regulating authority for transactions. While Southeast Asian governments’ have their reservations about Bitcoin, they are remarkably interested in the underlying technology called blockchain.

Breaking down the blockchain

At its most basic level, a blockchain is just a data structure combining different technologies into one, depending on an operator’s choice of configuration.

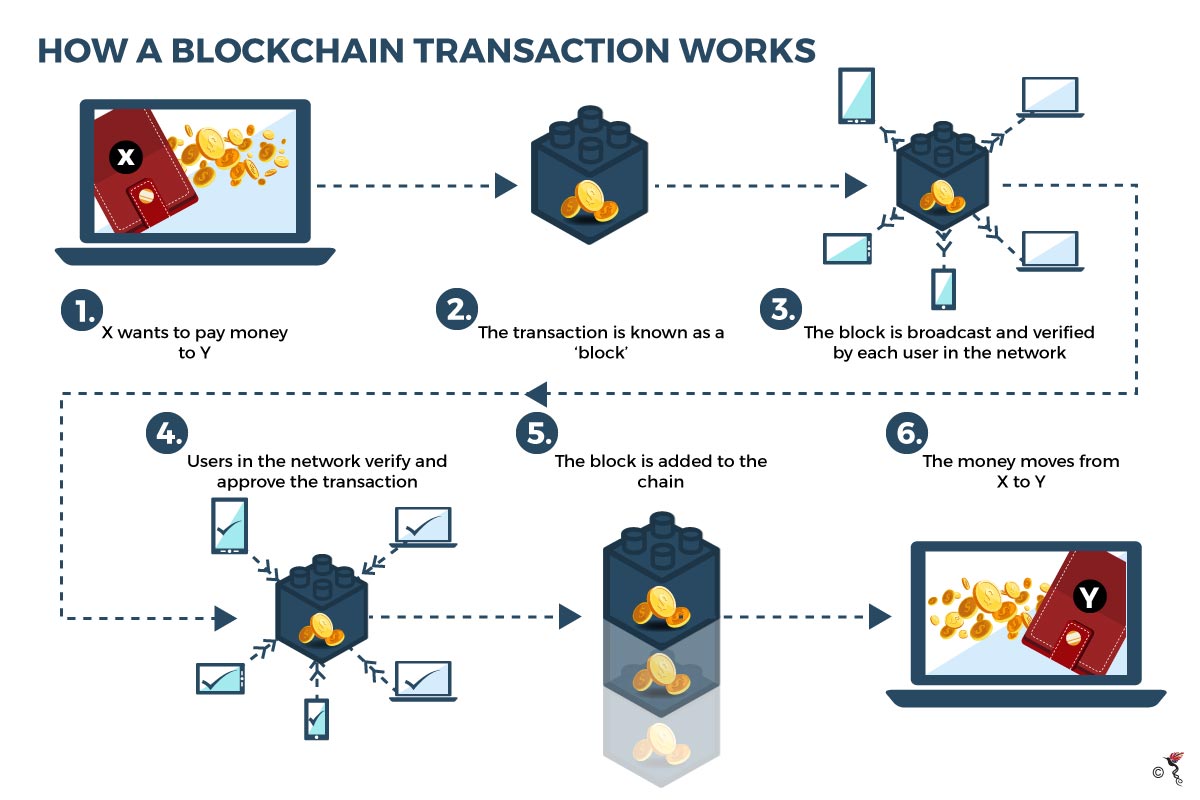

When you zoom in on a particular blockchain, you can observe that it is in fact operating as a digital ledger to which transactions can be regularly added to by solving difficult mathematical problems, or through cryptography. This ledger is shared among a network of computers, with each user, holding a node, who then runs algorithms verifying the authenticity of the transaction by comparing it against historical transactions.

Once the transaction has been verified, it will be added to the ledger as a block which contains both, the bitcoin transaction as well as data from the previous block. The chronological order of each record makes it difficult for any one record to be removed, because this would break the chain of reference to which future blocks are tied.

Because new transactions can only be added by consensus, with the ledger visible to each user, the system as a whole essentially self-regulates, without the need for a central regulating authority. Each user is issued a public key and a private key. The private key remains hidden on the computer but the public key operates as a kind of address from which a user can receive and issue payments to other users.

Practical applications of blockchain

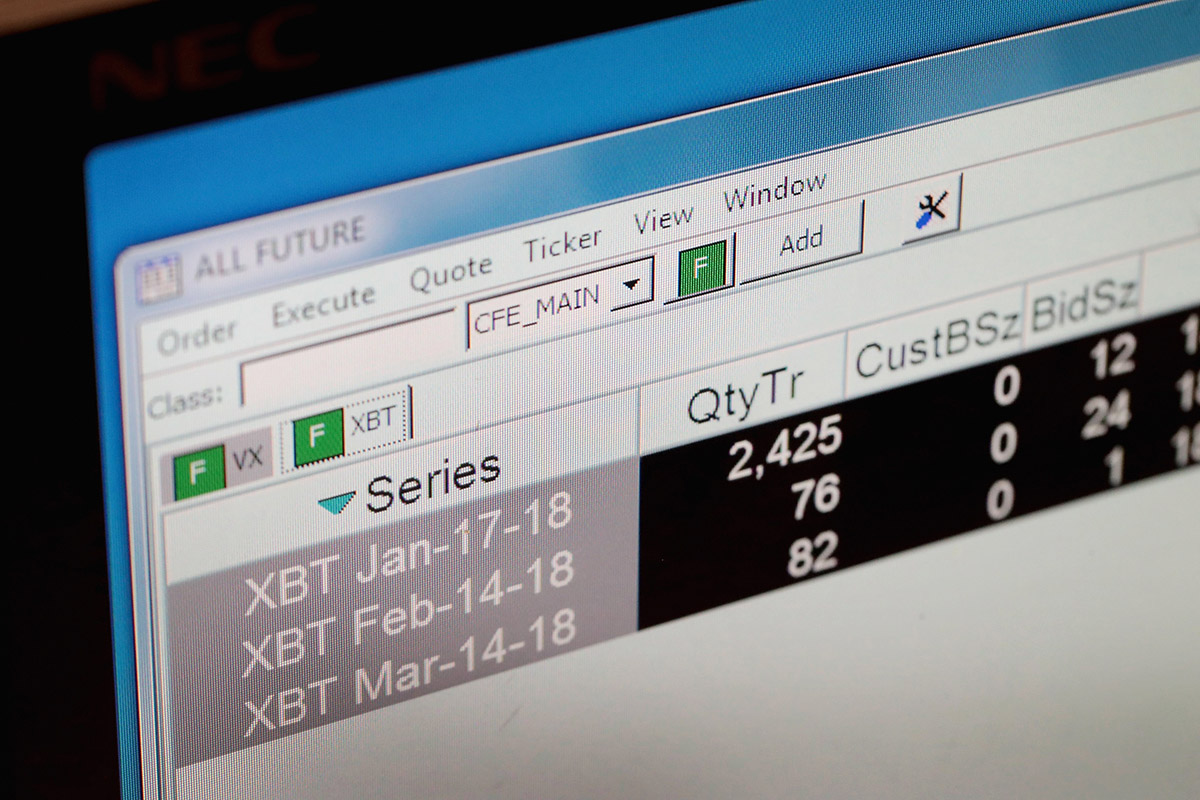

Blockchain has the ability to record almost anything of value, but is best known as the technology that undergirds the Bitcoin cryptocurrency. It provides the framework by which Bitcoins are mined and earned. The process of Bitcoin mining essentially also describes the process of writing new blockchain transactions: users race to solve a computational puzzle, the first user who succeeds gets to add a block to the chain (writing the transaction to the ledger) and claims the Bitcoin reward that follows.

The rules of blockchain inform the structure of the Bitcoin, which is owned relatively anonymously, yet is transacted accountably, with a permanent record of transactions laid down.

The structure of the Bitcoin also represents a public blockchain, which allows just about anyone to write new transactions into the digital ledger so long as they can solve the cryptography involved.

Private blockchain structures, on the other hand, are also known as permissioned blockchains where only identified participants are allowed to enter transactions. Operators can select a few users to perform the verification process, which once done, they will communicate to everyone else. In this way, because of the lower barriers to verification, the verification process (also known as the consensus protocol), takes up far less time to complete compared to public blockchains.

It is the use of private blockchains where market potential is the strongest, as an enterprise solution helping to save time and money, as well as track process flows.

Shipping company Maersk, for instance, uses blockchain to track its cargo as it passes from port to port. In Southeast Asia, this technology has the potential to trace palm oil as it is processed through the supply chain. It could also be used in food safety to ensure that imported food items are sourced from reputable, certified producers whose transactions have been verified on the digital ledger. The potential is also one of the largest for financial services, especially where clearing and settlement, payments services and trading platforms are concerned.

It is the peer-to-peer nature of blockchain transactions that provides the potential of cost savings. For banks, this would remove the need for intermediaries like clearinghouses, as well as trim down infrastructure spending on areas such as financial reporting and compliance.

European bank Santander, for instance, in 2015 projected savings of up to US$15-20 billion on infrastructure costs alone, by 2022.

Closer to home, changes have already started taking place too. In November 2016, a pilot cross-border transaction was completed between OCBC Malaysia and OCBC Singapore using a customised blockchain payments system. Singapore, on the other hand is working to improve their 'know your customer' (KYC) processes using blockchain in collaboration with OCBC Bank, HSBC and Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group (MUFJ).

With the ever-growing potential of blockchain being used to revolutionise traditional industries, it is just a matter of time before blockchain truly causes a disruption. But first, it will need to gain the confidence of governments.

Recommended stories: