The recent introduction of facial recognition technology by popular low-cost airline, AirAsia, to shorten security queues could also have utility in countering the terrorism threat in Southeast Asia. Even so, effective implementation for that purpose will need to be counterbalanced by sound regulatory laws.

The new facial recognition technology, known as the ‘Fast Airport Clearance Experience System’ (FACES) is currently being tested in Johor’s Senai International Airport in Malaysia. According to reporting by The Borneo Post, the system has an 80% success rate for identification and reduces boarding times from between an average of 11-13 minutes to just 9-11 minutes. Singapore’s T4 at Changi Airport also employs facial recognition tech to automate its passenger boarding processes.

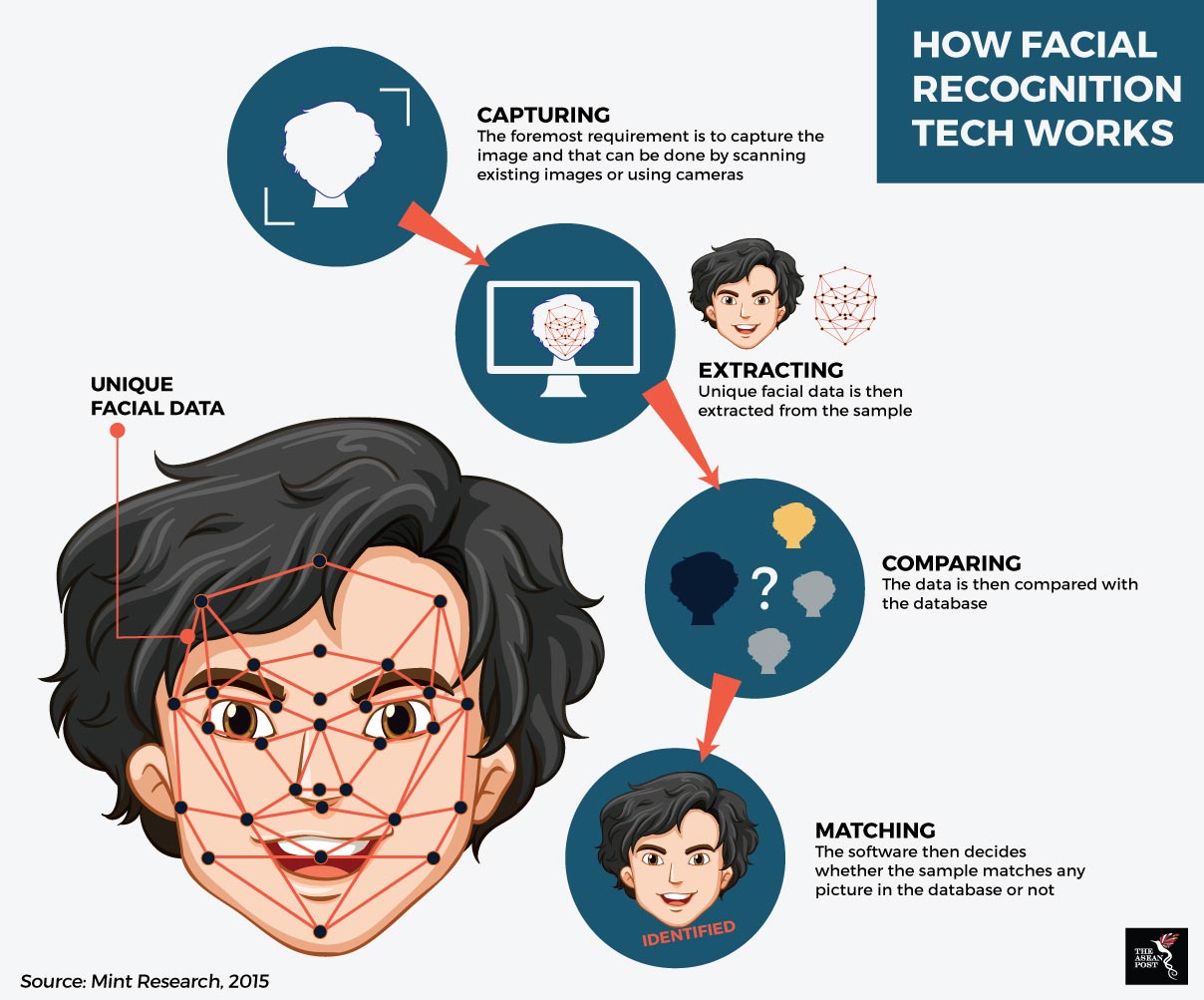

Facial recognition tech is defined as biometric software capable of uniquely identifying or verifying a person’s identity by comparing and analysing patterns based on a person’s facial contours, according to IT education website, Technopedia.

Facial recognition tech can be installed in various ways, including CCTV cameras, security equipment and even sunglasses. It was reported by BBC News recently that sunglasses installed with facial recognition tech were used in the arrest of seven people at China’s Zhengzhou East Railway Station. 25 criminal suspects were also effectively identified and arrested at the Qingdao Beer Festival in 2017 using facial recognition tech installed in 18 CCTV cameras, according to reporting by China’s Xinhua. Other governments, including Germany’s, are also testing facial recognition tech in a bid to prevent terror incidents like the truck attack on Berlin’s Christmas market in 2016 from happening again.

Currently, facial recognition tech is not widely used in Southeast Asia as a means of combatting terrorism, but this is likely to change in the future. ASEAN defence ministers recently agreed at the ASEAN Defence Ministers’ Meeting (ADMM) Retreat in February 2018 that the increasing scale and complexity of terrorist threats in ASEAN will entail the use of new methods and strategies to thwart them.

The ‘Our Eyes’ initiative was recently launched by Indonesia, Singapore, Malaysia, Philippines, Thailand and Brunei to facilitate intelligence sharing between the countries, of which data gathered from facial recognition technology could possibly form a part of. The Diplomat reported in January this year that implementation of the initiative is still under discussion and is most likely to be ironed out in subsequent meetings.

The need for regulatory frameworks

The usefulness of facial recognition tech in countering terrorism can only increase in parallel with sophistication levels of the tech itself, but this would also highlight the risks of data privacy in managing large-scale data collection.

Data privacy laws are currently sparse in Southeast Asia. Only the Philippines, Singapore and Malaysia have dedicated data protection laws in place, according to global intellectual property consultancy firm, Rouse. It is arguably difficult to define the scope of data privacy laws where the precise area of technology, and the exact uses of any data collection is still undergoing definition. Yet in the interim, the existence of a basic regulatory framework governing the collection and use of this data should be sufficient enough protection for citizens.

Southeast Asia may also be able to look to international jurisdictions for inspiration on the effective implementation of data privacy laws governing facial recognition technology. Australia recently introduced two Bills which would allow its Department of Home Affairs to operate a central hub for transmitting facial recognition requests between government agencies, but not to keep such photo records itself.

“To be clear about this, this is not accessing photo ID information that is not currently available,” stressed Malcom Turnbull, the Australian prime minister. In other words, it was merely facilitating requests for data that had already been requested for by the various government agencies.

It is also only too easy for governments to tip the balance of its interests towards exercising iron controls over its citizens instead of merely conducting surveillance. A 2017 House Committee Oversight meeting in the United States revealed that approximately 80% of photographs stored on FBI databases are non-criminal entries, for example, passport photos and photos obtained from driving licences. The FBI launched its biometric database in 2010, but did not publish a public privacy assessment until 2015, The Guardian reported in 2017.

An extreme example is also seen in the level of surveillance China employs in Xinjiang state, tracking the whereabouts of the largely Muslim Uighur minority living there. Authorities receive alerts when targets are said to stray more than 300 metres from designated “safe areas”. According to reporting by The Guardian, China sees this level of surveillance as justified due to the fact that some members of the Uighur population have previously been recruited by the Islamic State.

A healthy use of facial recognition tech in combating terrorism can only grow in parallel with the development of regulatory laws in Southeast Asia. Each ASEAN country must find a balance between national security interests and the interests of their own citizens when developing regulation for facial recognition tech usage. Only then will they be able to combat terrorism effectively as a region.

Recommended stories: