In December 2015, recognising the need for an effective and progressive response to climate change, the world’s leaders came together to commit to a landmark agreement under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). The Paris Agreement pledged to hold “…the increase in the global average temperature to well below two degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels and pursuing efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5 degrees Celsius”.

However, as climate change impacts under a two-degree Celsius increase is still damaging for some low-lying and small island areas, the UNFCCC requested that the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) – the international body for assessing the science related to climate change – to provide a review on the difference between 1.5 and two degrees Celsius.

The special report on Global Warming of 1.5 degrees Celsius (SR15), released this week, confirmed that the global atmospheric temperature has increased approximately one degree Celsius above pre-industrial levels, the period before the dawn of the industrial revolution. The report projected that at the current rate of human activity, global warming is likely to reach a 1.5 degrees Celsius increase between 2030 and 2052.

Disproportionate magnitude

The difference in the magnitude of exposure, risks and impacts to the natural and human systems between 1.5- and two degrees Celsius and beyond is disproportionately wide. This cuts across sea-level rise, extreme weather events, habitat loss, biodiversity loss, natural resource loss, human health, livelihoods, food security, water supply, human security and economic growth.

SR15 stresses that despite a wide range of climate change adaptation options available, even at a 1.5 degrees Celsius increase, there are limits to how much the natural and human systems can adapt to the climatic changes. This adaptive capacity limitation becomes even more pronounced at two degrees Celsius or higher.

By 2100, the global mean sea level rise is projected to be around 0.1 metres lower with global warming of 1.5 degrees Celsius compared to two degrees Celsius. According to SR15, a reduction of 0.1 metres in global sea level rise implies that up to 10 million fewer people would be exposed to related risks.

"Sea levels will continue to rise well beyond 2100, and the magnitude and rate of this rise depends on future emission pathways. A slower rate of sea level rise enables greater opportunities for adaptation in the human and ecological systems of small islands, low-lying coastal areas and deltas.”

How will Southeast Asia fare?

Southeast Asia is one of most vulnerable regions to the impacts of climate change, threatening to disrupt the remarkable expansion of its economies and undo the hard-earned achievements of its sustainable development. This is due to the location of the region’s urbanisations and economic capitals that are concentrated along its coastline and within deltas, as well as its economic reliance on agriculture and natural resources.

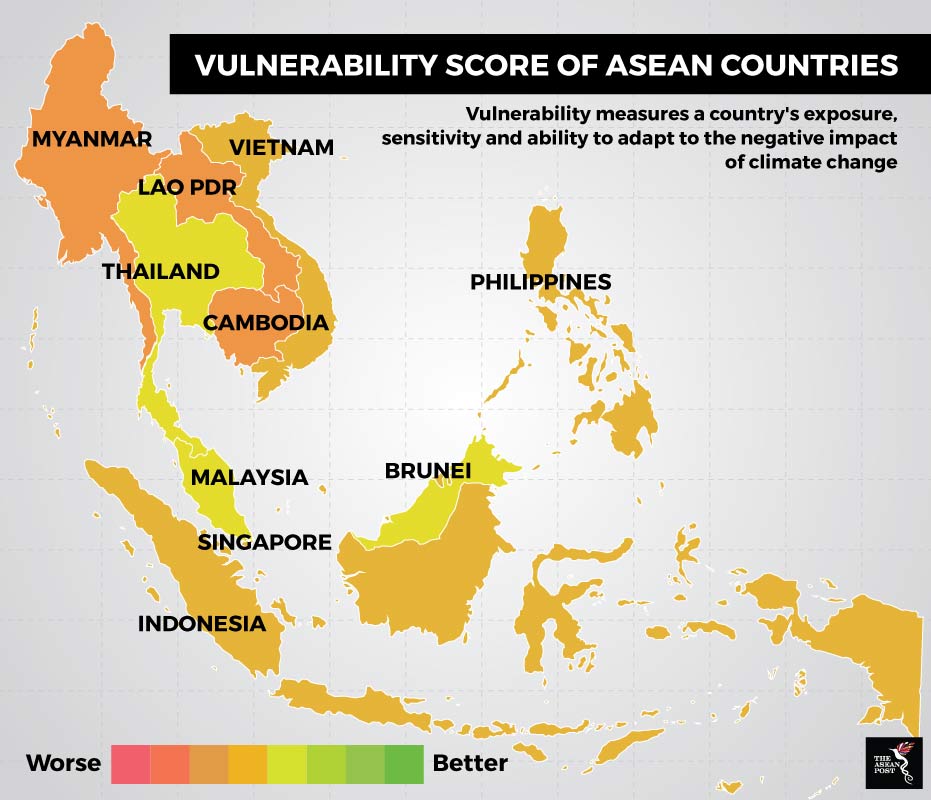

The study on Global Adaptation Index by the University of Notre Dame (ND-GAIN) ranks countries on their propensity or predisposition to be negatively impacted by climate hazards, and readiness to make effective use of investments for adaptation actions. In 2016, four Southeast Asian countries, namely Singapore, Malaysia, Brunei, and Thailand were categorised as low vulnerability and high readiness. Vietnam was categorised as high vulnerability but high readiness. The rest – Indonesia, the Philippines, Lao PDR, Cambodia and Myanmar – were categorised as high vulnerability and low readiness.

Source: ND-GAIN

Source: ND-GAIN

The ND-GAIN also identified prioritised areas for improvement for each country. Throughout the region, projected cereal yields, medical staff, agricultural capacity and dam capacity were regularly identified as lowly scored. The Philippines, Singapore and Thailand need to look at their dependency on imported energy, Lao at its unpaved roads, and Malaysia for its dependency on imported food.

In the SR15, specific mention was made about food security, in which it warned of reduction in yields of rice, a staple food and key agricultural product of many southeast Asian countries, as well as maize, wheat and other cereal crops. The nutritional quality of rice and wheat, which is dependent on CO2, is also projected to reduce in a warmer climate.

It is clear that even half a degree of additional warming will add hundreds of millions of people to the affected population. 12 years seems like an extremely short time to make the necessary changes. However, the tools and expertise are available. Nothing short of “rapid, far-reaching and unprecedented changes” is needed. While it is a monumental task, it is achievable. Not doing anything about it however, is simply unacceptable.

Related articles:

US accused of blocking UN climate talks