Whenever Malaysia wishes to get under Singapore’s skin, it seems, all it has to do is talk about their bilateral water agreement. A brief remark by Malaysia’s Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad in an interview on Bloomberg Television on 22 June drew a swift and curt response the following Monday from Singapore’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA).

Mahathir had said that water was among the issues with Singapore that need to be settled. “We will sit down and talk with them, like civilised people," he said.

The MFA cited both, the 1962 Water Agreement and 1965 Separation Agreement which were registered with the United Nations (UN). “Both sides must comply fully with all the provisions of these agreements,” it said in a statement.

Mahathir subsequently said the issue was “not urgent” and not even discussed with his Cabinet. He was “pressed” into making that remark after being “asked by the press.” Clearly it was a game of “chicken” and Singapore blinked first.

Having won the general election in an upset victory, Mahathir was keen to reduce the nation’s debts by cancelling or renegotiating the terms of expensive mega-projects agreed upon during the administration of his predecessor, Najib Razak. One of these is the High Speed Rail (HSR) project linking Singapore to Kuala Lumpur.

The water issue may be a veiled message to encourage Singapore to be more “reasonable” in negotiations. Singapore’s former ambassador-at-large Bilahari Kausikan wrote on his Facebook page that the water issue was raised as a diversionary tactic to seek a waiver or reduction of compensation for the HSR’s cancellation.

Malaysia has yet to officially notify Singapore of its decision to terminate the HSR but Singapore’s Minister of Transport, Khaw Boon Wan already issued a statement that Singapore will “exercise our rights, including any right to compensation for expenses incurred in accordance with the terms of the HSR Bilateral Agreement.”

Disagreement over agreements

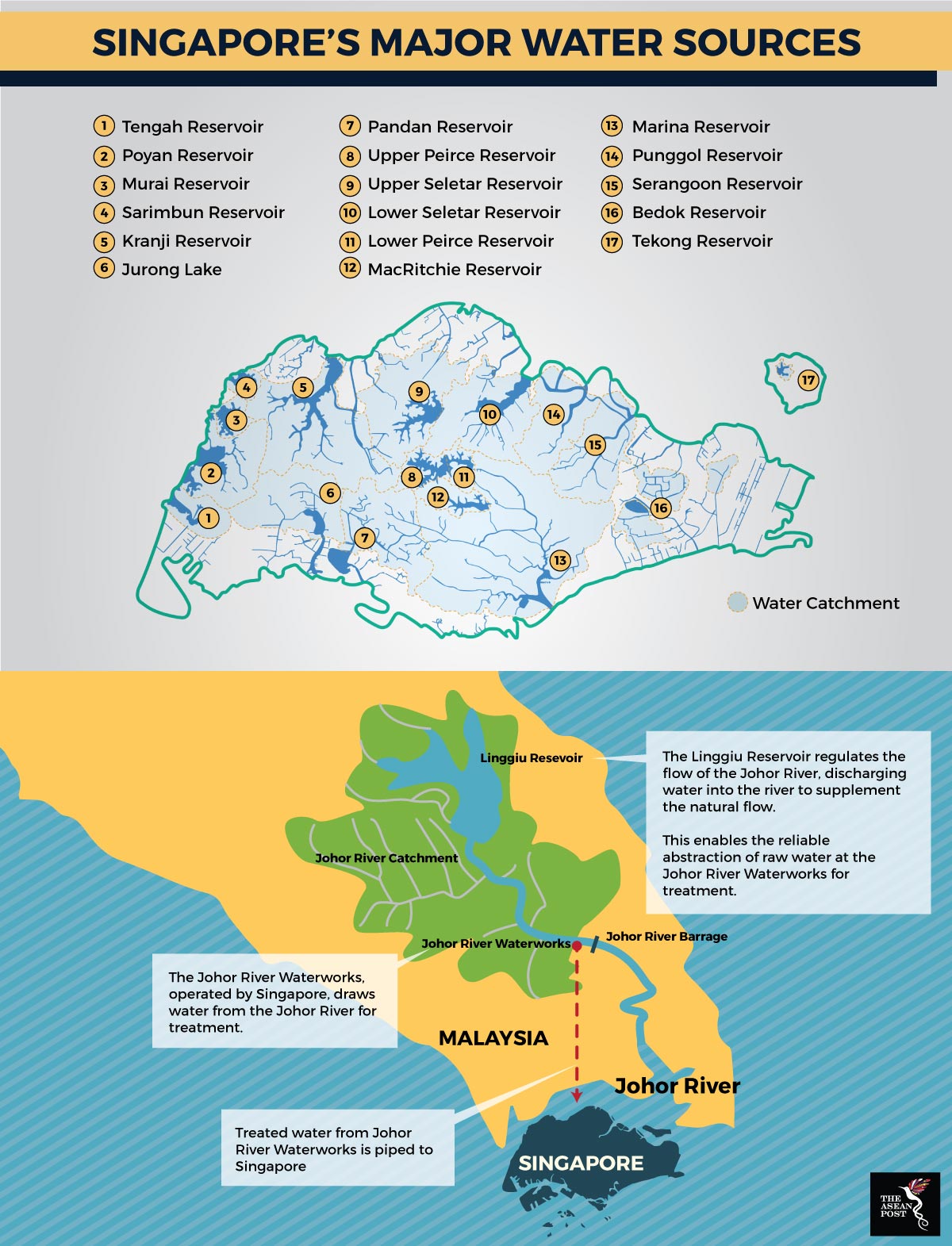

Singapore bristles at any suggestion of having to renegotiate the terms of the 1962 agreement, as imported water comprises about 50 percent of current demand. The agreement grants Singapore the rights to draw up to 250 million gallons per day (mgd) of raw water from the Johor River at RM0.03 per 1,000 gallons (US$0.02 per cubic metre). In return, Singapore sells up to two percent of this volume as treated water back to Johor at RM0.50 per 1,000 gallons (US$0.33 per cubic metre).

Singapore also has an agreement that was inked in 1990 to construct the Linggiu Dam and increase the yield of the Johor River. It was supplemental to the 1962 agreement which expires in 2061.

Source: Singapore Public Utilities Board

Source: Singapore Public Utilities Board

Another agreement, signed in 1961, was allowed to expire in 2011. Malaysia had wanted to increase the price of raw water to RM0.60 per 1,000 gallons (US$0.04 per cubic metre) in 1998 and include a clause for periodic reviews.

Singapore insisted that Malaysia forfeited that right when reviews provisioned in the 1961 and 1962 agreements were not exercised in 1986 and 1987. Both countries engaged in a regional tit-for-tat public relations war until 2003, when Singapore abandoned talks and decided that it will become self-sufficient by 2061.

It launched the Four National Taps program, to rebalance its water sources by tapping into modern technologies such as wastewater reclamation and water desalination.

Water security

When the 1961 and 1962 agreements were negotiated and signed, Singapore was on the brink of joining the Federation of Malaya, North Borneo (now Sabah) and the Sarawak Crown Colonies to form Malaysia in 1963. Hence, the low price for water.

Singapore left Malaysia in 1965 and the Separation Agreement signed by both countries guaranteed the 1961 and 1962 agreements.

Indonesia had then engaged in a confrontation with Malaysia, in opposition to the latter’s formation. Then-Malaysian prime minister Tunku Abdul Rahman worried that newly-independent Singapore may side with Indonesia. He reportedly said “If Singapore’s foreign policy is prejudicial to Malaysia’s interests, we could always bring pressure to bear on them by threatening to turn off the water in Johor.” The lesson was not lost on Mahathir.

This was not the first time Singapore’s security was threatened with water. During World War II, British troops bombed the Causeway to stop the advancing Japanese army and destroyed the pipeline supplying water to the island. It was left with only two weeks of reserves.

Singapore was so determined to protect its water supply that former prime minister Lee Kuan Yew purportedly said he was prepared to send troops if Malaysia ever decided to cut off the water supply.

Even without political manoeuvring, Singapore’s water supply was disrupted when a prolonged drought hit Malaysia and Singapore in 1963. It had to implement water rationing for 10 months.

During British rule, Singapore built the MacRitchie, Lower Peirce and Upper Seletar reservoirs. Additional reservoirs have since been built by damming up river estuaries to store the water.

The largest and most renowned is the SGD226 million (US$165 million) Marina Bay reservoir. Covering 10,000 hectares or one-sixth of Singapore’s land size, it can meet 10 percent of Singapore’s current water needs. The reservoir is formed by the Marina Barrage which keeps seawater out of the Kallang Basin.

It acts as a tide control barrier, is part of a recreational park and is also touted as a comprehensive flood control scheme for the city’s low-lying areas such as Chinatown and Geylang. If water levels in the reservoir rise, crest gates can be opened to discharge water into the sea. If the sea level is higher, drainage pumps will be used.

The Ministry of the Environment and Water Resources (MEWR) declared that Singapore’s “flood-prone areas will be further reduced to less than 100 hectares (1 square km).”

Ironically, Singapore was subsequently hit with unusually heavy rainfall. Flash floods hit the city with increasing frequency: six days in 2010, nine in 2011, eight in 2012, 10 in 2013, six in 2015, 10 in 2016 and 14 in 2017.

The government engaged a panel of experts to examine the cause of the so-called Great Orchard Road Flood of 2010. It concluded that the Marina Barrage was not responsible.

Four Taps

Singapore’s Public Utilities Board was given full responsibility for sanitation and storm water drainage in 2001, taking over from the Ministry of Environment. It is responsible for managing the National Four Taps policy.

The first tap involves creating local water catchments. Apart from the Marina Bay reservoir, barrages were also constructed to form the Punggol and Serangoon reservoirs. The collection of rainwater in drains, canals, rivers and storm water collection ponds effectively turns two-thirds of Singapore’s land into a water catchment area.

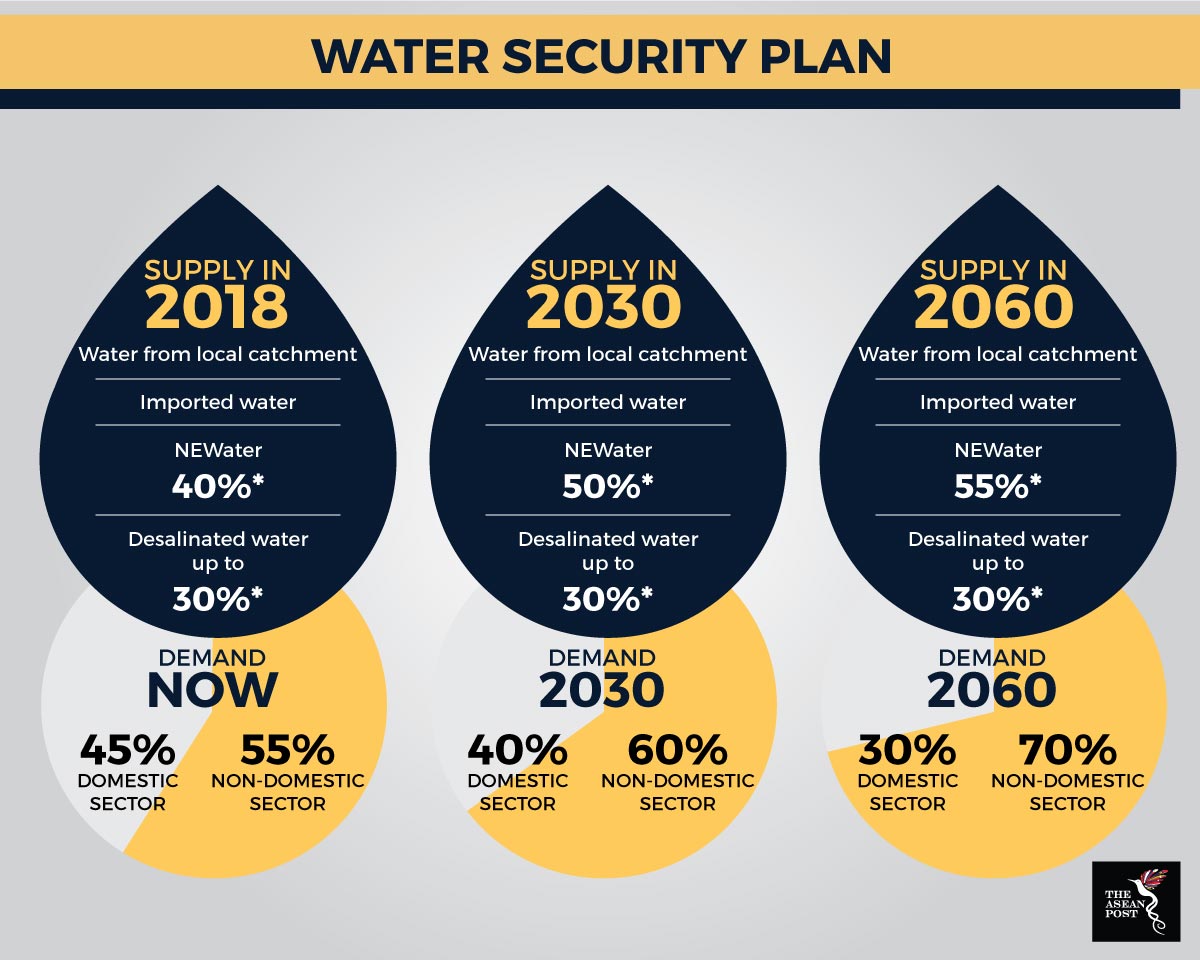

The second tap concerns water imports which the government is preparing itself to forego by 2061, when the 1962 water agreement ends. Imported water currently fills almost half of Singapore’s daily 430 mgd requirements.

Work on the third tap, reclaiming wastewater, began in 1998 with the NEWater Study to treat “reclaimed” water and convert it into potable water. Extensive studies were done to monitor its safety and by 2002, the first NEWater plant was operational. The government launched a major marketing campaign to garner public acceptance: NEWater was sold in bottles and then-prime minister Goh Chok Tong drank from one in a publicity campaign.

Water from sewage systems is first treated at conventional advanced treatment or reclamation plants. The effluent is channelled to NEWater plants which purify it using dual-membrane and ultraviolet technologies. NEWater is said to exceed World Health Organization (WHO) standards for drinking water. Most NEWater, however, is used by industries that require high purity water.

Plans are underway to centralise NEWater plants to enjoy economies of scale and reduce cost. Currently, a 1.48 km Deep Tunnel Sewerage System (DTSS), buried 20 to 55 metres below ground, channels sewage into a centralised treatment facility. The DTSS runs on gravity and does not require pumping stations, thereby averting the risk of overflows.

Another DTSS, to be finished in 2022 will span the island and lead to a second treatment plant in Tuas.

The government expects NEWater to meet up to 40 percent of Singapore’s current water needs and up to 55 percent by 2060.

Tap four is water desalination, an energy-hungry process to purify water by extracting salts from seawater. Singapore has three desalination plants with a combined capacity of 130 mgd. Two more, the Keppel Marina East and Jurong Island plants are expected to be ready by 2020. The combined output of all five is expected to supply up to 30 percent of the nation’s needs by 2060.

Source: Singapore Public Utilities Board

Source: Singapore Public Utilities Board

Singapore’s advancements towards water self-sustainability has made it a global leader in water management and technology. It is now exporting its capabilities to markets in the Middle East and China.

The government there is also stepping up efforts to reduce water usage per person. In March, Minister of the Environment and Water, Masagos Zulkifli told parliament that daily water consumption per person fell from 148 litres in 2016 to 143 in 2017, exceeding its target of 147 litres by 2020. The next milestone is 140 litres by 2030.

The reduction in consumption was likely due to economic reasons: the government raised domestic water prices in 2017, its first in 17 years. To reduce the shock, the hike was spread over two years. As of 1 July, 2018, domestic consumers must pay US$2.00 per cubic metre (from US$1.53) for the first 40 cubic metres, and US$2.70 (from US$2.35) for subsequent amounts.

Singapore appears to be on-track to full self-sustainability just before the 1962 water agreement expires. However, judging by its response to Mahathir’s remarks, it is not quite there yet.