The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) as a collective of 10 economies has made immense strides over the past 51 years. A significant milestone for the bloc was the establishment of the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) in 2015 which aims to achieve a vision for a dynamic and competitive market encompassing all 10 states.

At the crux of such an ambition is the huge potential of a demographically young region of over 630 million people – with 60 percent below the age of 30. Over the past two decades, an estimated 100 million people have joined the ASEAN workforce. According to a recent report, this trend is expected to continue in the medium term albeit at a slower pace than before.

Nevertheless, the International Labour Organisation (ILO) projects that between now and 2030 ASEAN will record the second largest growth in terms of its labour force, behind only India. By 2030, approximately 59 million people are projected to enter the region’s workforce, boasting a total labour force of 175 million. By comparison, ASEAN’s labour force would be more than double that of the next ranked market, the United States (US). This means that ASEAN will continue as the third largest labour force in the world – accounting for 10 percent of the global workforce by 2030.

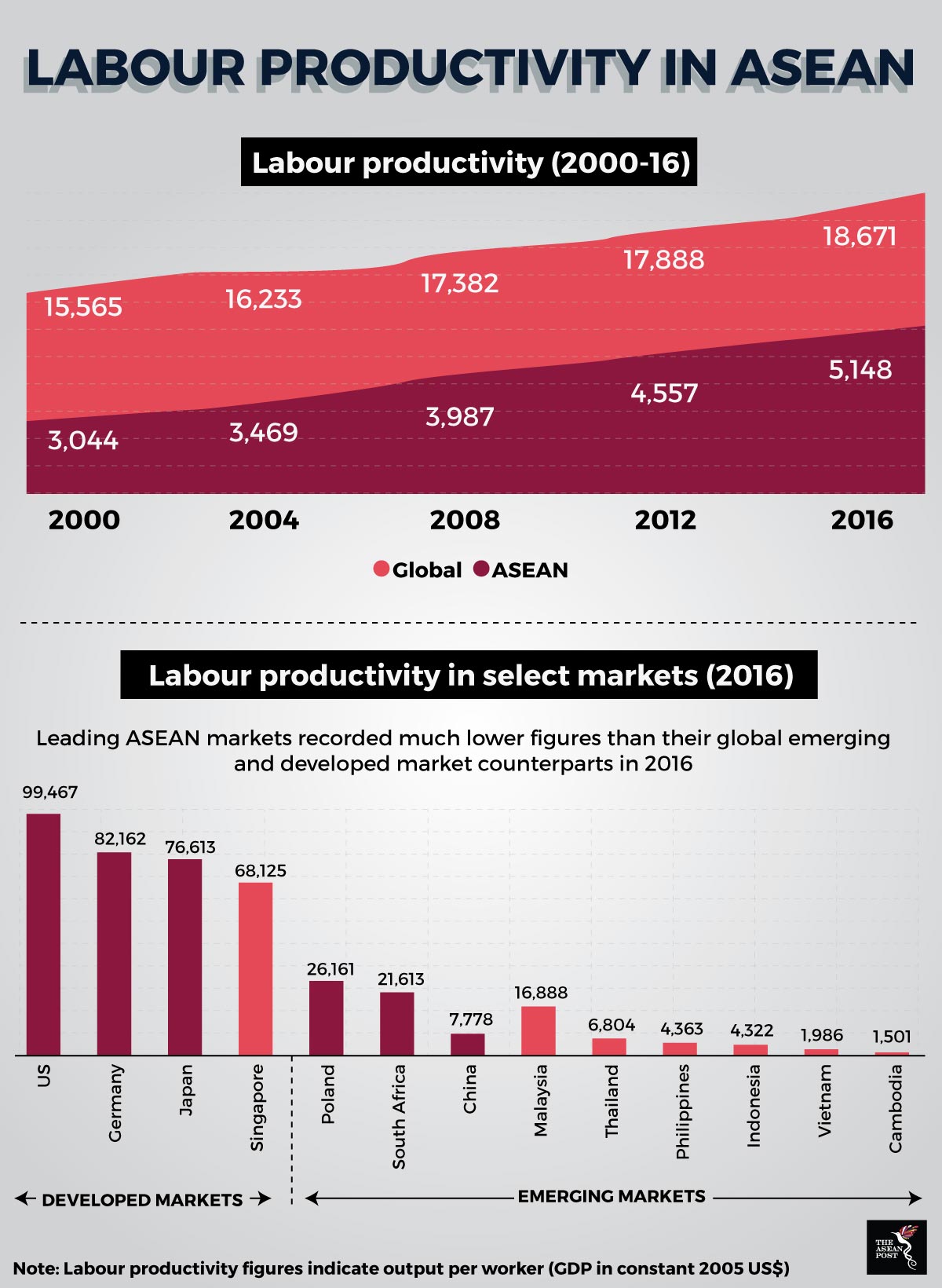

While these figures are impressive, the failure to actualise them could result in a tremendous economic loss for the region. Hence, the ability to sustain impressive economic growth rates and to achieve the forecasted average growth of 5.1 percent is contingent on how productive ASEAN’s labour force is.

Challenges to labour productivity

In a competitive global economy, stagnation of productivity is a prime concern.

More developed ASEAN economies like Singapore and Brunei are better equipped with advanced institutions and infrastructure. However, relative to other nations, they have an older population which would require swifter technology adoption to counter declining productivity growth.

Opposingly, emerging economies like Cambodia, Myanmar and Lao PDR with their relatively weaker business environments and infrastructure have more levers to pull to rally productivity. However, fast-rising wage levels threaten to dilute the low-cost advantage enjoyed in such markets. In order to stay competitive, these countries need to improve worker productivity and balance growing labour costs.

Source: Various sources

Other ASEAN markets like Vietnam, Thailand and Indonesia have recorded higher projections of real wage increases – Vietnam (7.2 percent), Thailand (5.6 percent), Indonesia (4.9 percent) – compared to the global average of 2.3 percent. This may place further pressure on these economies as they strive to achieve their long-term economic prospects.

Mobilising ASEAN’s growing middle class

From a demand perspective, proper utilisation of ASEAN’s labour force will likely depend on the region’s expanding middle-income segment of society. This percentile, which in 2010 only represented 29 percent of the population, is anticipated to represent two thirds of the overall population by 2030.

With this emerging middle class, comes an increase in demand for higher quality goods and a willingness to pay for convenience and more choice. Hence, demand for more discretionary and aspirational products will likely see an increase in the next decade.

Therefore, companies in the region must be sensitive to this change in consumption patterns and adjust their business strategies accordingly. End users will expect a higher quality of goods and increased safety standards alongside improved order visibility and fulfilment. Hence, businesses may look into advancements in technology to help meet these expectations.

This will also have a ripple effect on the wider talent pool where more skilled and innovative labour will be preferred. Accordingly, the future workforce must be trained in the skills required for such higher value-add jobs which will help further boost labour productivity levels. All these shifts will translate to greater growth challenges which must be met in order for companies to satisfy local tastes while anticipating the ever-changing contours of the market.