In 1930, economist John Maynard Keynes wrote in an essay titled “Economic Possibilities For Our Grandchild” that with the technological advancements of the future, people could be working as little as 15 hours a week. Just like the industrial revolution, many thought the introduction of automation in workplaces in the 21st century would revolutionise labour – freeing workers from long hours at the factory and spend more time on leisure activities.

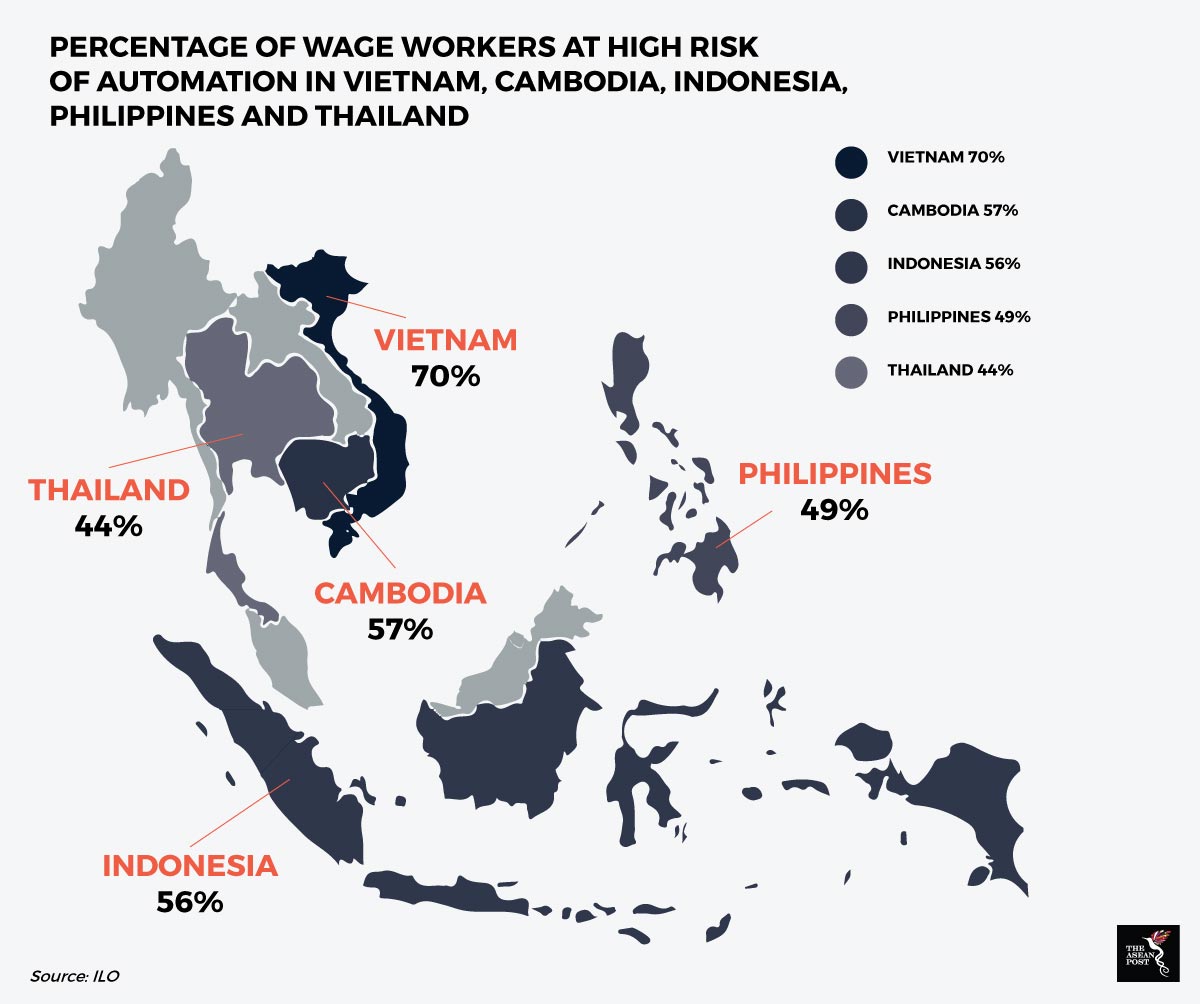

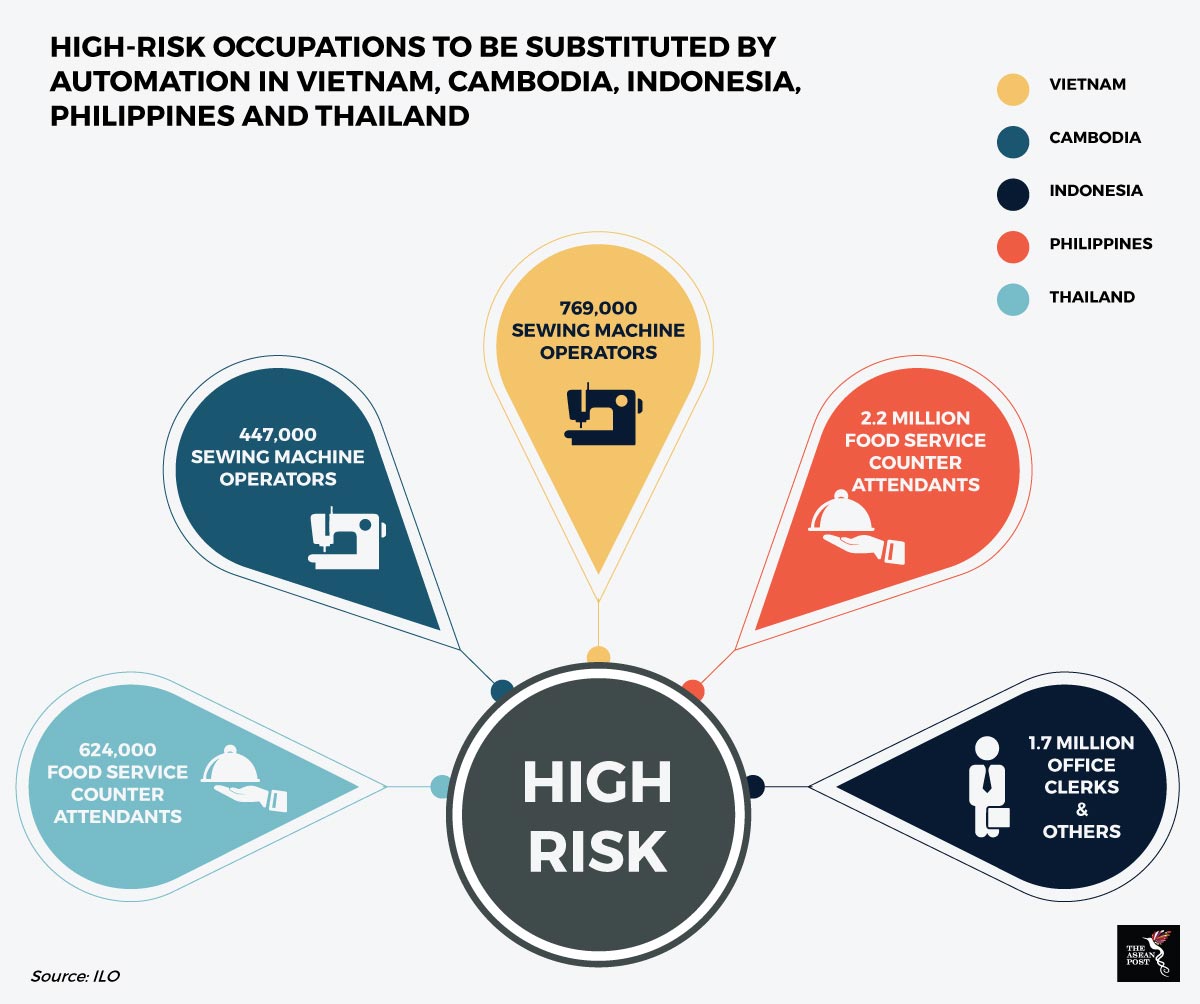

However, with more and more jobs being substituted with technology and robots in the past decade, people have become sceptical of the notion that automation would bring about more freedom. In a study that involved 46 countries and carried out by the McKinsey Global Institute last year, it is reported that up to 800 million global workers might lose their jobs by 2030. On a more regional level, the International Labour Organisation (ILO) has also said in a report titled “ASEAN in Transformation”, half of the salaried workers – approximately 137 million workers – in Cambodia, Indonesia, Vietnam, the Philippines and Thailand might lose their jobs in the next 20 years.

Automation has become increasingly attractive to investors as it’s often deemed more efficient and has a lower operational cost compared to paying workers wages. Previously it was thought that automation would occur the most in developed countries as wages in developing countries were still low enough to justify maintaining a traditional workforce to keep operational costs low. However, the World Bank have argued otherwise, claiming that developing countries face greater vulnerability to automation due to having more low-skilled jobs.

While automation has yet to completely overtake the traditional workforce in Southeast Asia, it is clear that more and more companies in the region have started looking at automation. For example, Thailand’s “Thailand 4.0” campaign aims to have 50 percent of its manufacturing automated within the next five years. In a report by Bloomberg, the Philippines call centre industry, which is one of the largest in the world is also being threatened by automation.

If reports by the ILO that half of the labour force in the aforementioned ASEAN countries could be displaced in two decades are true, ASEAN governments need to act quickly before it’s too late as their workforce will be heavily impacted by it. According to the same report, women are among the most impacted by automation in this region. The report mentions that in the Philippines and Vietnam, women are twice as more likely to be in a high-risk occupation than their male counterparts.

Another thing to note is that disruption due to automation will be worse in developing countries compared to developed countries as educational levels are relatively low in this region. In the paper by the ILO, it was found that 90 percent of Cambodia’s workforce only has a secondary education while the number is 75 percent in Vietnam along with 67 percent in Thailand and Indonesia. If these workers were displaced many of them will have little options elsewhere nor do they have opportunities for social mobility. An overlooked consequence of a displaced workforce is the possible dent it would cause to the local economy. As more people lose their jobs, there would be naturally less spending in the economy.

Since many ASEAN economies depend on low-skilled workers, ASEAN governments need to anticipate and prepare for the possibility of a sudden displacement of large segments of their respective workforces. The ILO has suggested that this could be a great opportunity for governments in affected countries to consider investing in education to offset the effects of automation. Investing in education would create a more dynamic and high-skilled workforce that could weather the challenges of a changing job landscape.

There have also been suggestions by economists to tax companies that profit from automation. The taxes collected could then be used in numerous ways, such as funding re-training programmes, education or even implementing a basic national income – which would realise Keynes dream of reducing working hours. This idea has actually been made into policy by South Korea last year – making it the first country in the world to introduce a ‘robot tax’.

As the world goes further into the 21st century, automation is inevitable. Automation itself shouldn’t be seen as a bad thing as it has also made workplaces safer and more efficient. However, governments must act to ensure that automation complements the traditional workforce rather than becoming its competitor.

Recommended stories: