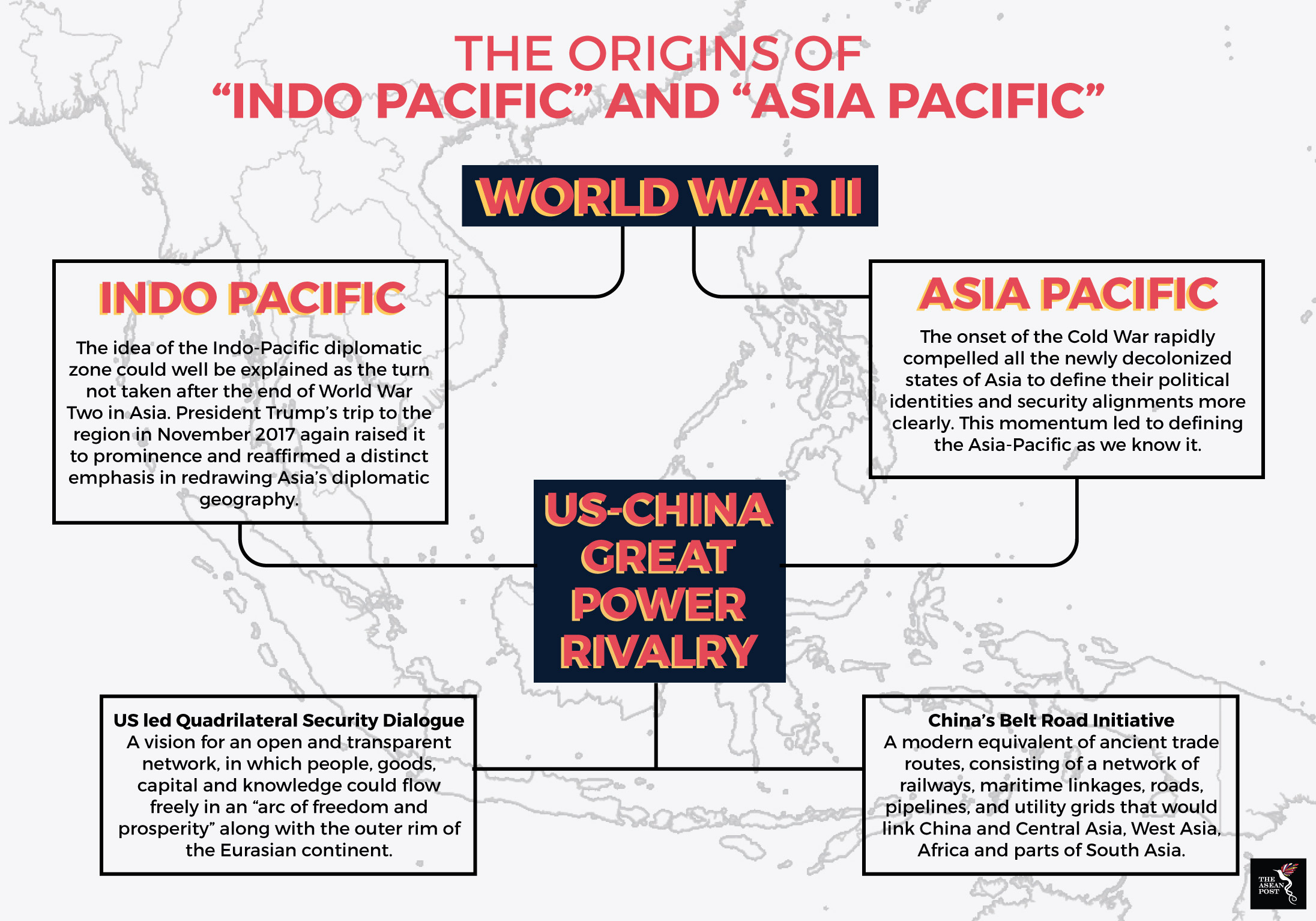

The term Indo Pacific gained a lot of traction after the President of the United States (US), Donald Trump, used it repeatedly to highlight his country’s foreign policy posture in this region as opposed to the regularly used term, Asia Pacific. The reason for doing so would seem simple enough – to contain China’s rise.

Linguistics is a cardinal factor in diplomacy and through the use of the term Indo Pacific the Trump administration has sought to realign the focal point of a region which is increasingly being courted by Beijing’s orbit of influence. The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) – the grand infrastructure ambitions of Chinese President, Xi Jinping – has noticeably raised the eyebrows of the US and its allies which have always been ambivalent of Beijing’s intentions and plans. Besides that, the US has also been increasingly wary of China’s aggressiveness with regards to its maritime claims in the region.

Another key development which took place alongside the calls for a “free and open Indo-Pacific,” was the re-emergence of the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue or Quad. The Quad, which is made up of the US, Australia, Japan and India is not an old idea – having been first mooted by Japanese Prime Minister, Shinzo Abe in 2007.

Source: RSIS Commentaries

A shifting regional order

These developments point to a shift within the regional order.

Since the end of the Second World War, the US has always maintained a “hub and spokes” relationship with countries on this side of the world. The relationship meant that East Asian countries could gain access to the American market and in return, the US, gained strategic geopolitical partners in this region.

In recent times, the US has ensured the continuity of this dynamic even when less attention was paid to this region during the Bush administration. However, when Barack Obama was in the Oval Office, he turned US attention back to East Asia amidst growing concerns that China was fast establishing itself as the regional hegemon.

Nevertheless, in a post-Cold War era, great power states like the US and China can’t afford to only take the path of hard diplomacy. Hence, over the past few years, we saw both sides pulling out all the stops with displays of leadership charisma to grand banquets in order to woo states to their side.

Herein, the regional order once based on the “hub and spokes” system has changed to reflect what Gilford John Ikenberry, Professor of Politics and International Affairs at the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs, Princeton University, calls a “dual hierarchy.” It is characterised by a security hierarchy led by the US and an economic one by China with both powers competing for the loyalties of smaller states.

“In the end, it will be the middle states that have the ability to shift the regional order in one direction or the other - or to make choices to preserve the double hierarchy,” Ikenberry postulated.

Staying central

In order to preserve the delicate balance between the two, states must continue to rely on China for economic gain while not completely shunning the US, allowing for their security presence as a bulwark against Beijing.

Member states of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) have seemingly mastered the art of centrality – a cornerstone tenet of the organisation – by welcoming Chinese investments via the BRI which would aid their own individual development agendas. Besides that, except for Cambodia, other ASEAN member states have continued to maintain good strategic security ties with the US and its Quad counterparts against Chinese maritime assertiveness.

Ultimately, whether Indo Pacific or Asia Pacific, foreign policy is no longer a zero-sum game – especially for smaller states like ASEAN’s members. There is no shame in polygamy within the rubrics of international relations, but, in balancing the interests of a state against prevailing great power rivalry, it is difficult to delineate exactly the boundaries to which beyond that, a state falls within the sphere of influence of either great power.

Perhaps this is where linguistics plays a role. When there is a need to decipher the allegiance of a state, one need only listen and look out for the use of either term or both.