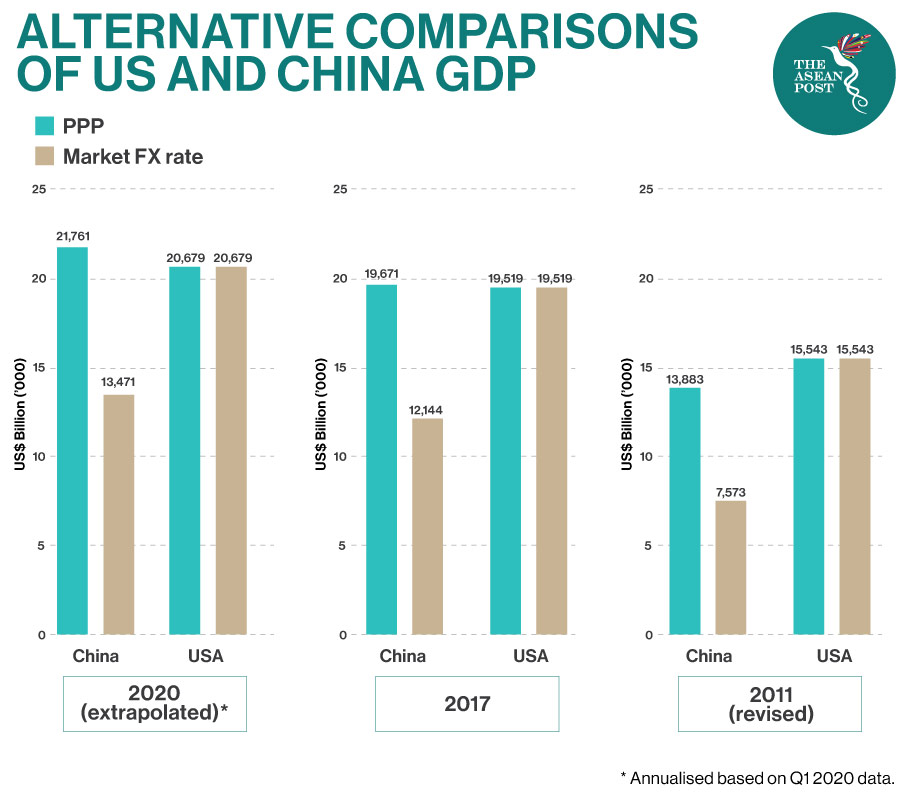

The World Bank’s International Comparison Program (ICP) has just released its latest measures of price levels and gross domestic product (GDP) across 176 countries, and the results are striking. For the first time ever, the ICP finds that China’s total real (inflation-adjusted) income is slightly larger than that of the United States (US). In purchasing-power-parity (PPP) terms, China’s 2017 GDP was US$19.617 trillion, whereas the US’s stood at US$19.519 trillion.

Of course, when China’s total income is divided by its massive population, the picture changes. Although China’s per capita income has pulled ahead of Egypt’s, it remains in the middle of the pack globally, behind Brazil, Iran, Thailand, and Mexico.

In any case, the two concepts – total and per capita income – each have distinct implications for geopolitics, so one must consider them separately. China wants to be treated like a developing country (at least in trade negotiations), and the ICP’s per capita income figure shows that it is precisely that. But when it comes to power politics and China’s influence in international institutions, total income matters more.

The ICP compares countries on a PPP basis, which is the right method when computing per capita incomes, but potentially problematic when assessing geopolitical power. On the latter question, a better approach would be to compare national GDPs at actual exchange rates, in which case the US economy turns out still to be far ahead of China’s.

When the ICP released its last report six years ago, it created a media flurry, with headlines such as the Financial Times’ “China poised to pass US as world’s leading economic power this year.” Those ICP measures, which pertained to 2011, showed that China’s GDP was gaining rapidly on that of the US. Soon thereafter, it was reported that the crossover had indeed taken place, at least according to national growth statistics interpolated between the six-year ICP benchmarks.

But, again, those findings were based on a PPP reading of the data. The problem, familiar to international economists, is that Chinese and US output are each measured in the country’s respective currency. How should one translate the numbers so that they are comparable?

The obvious solution is to use the contemporaneous exchange rate: multiply China’s renminbi-measured GDP by the US dollar-per-RMB exchange rate, so that it is expressed in US dollars. Viewed in these terms, the US economy (US$19.519 trillion) is still over 50 percent larger than China’s (US$12.144 trillion), according to the latest figures.

By contrast, measuring GDP in PPP terms is more appropriate for comparing standards of living, because it accounts for the fact that many goods and services are cheaper in China than they are in the US. Generally speaking, one RMB spent in China will go much further than one RMB spent abroad. While some internationally traded goods have similar prices, things like haircuts – a service that cannot readily be exported or imported – are cheaper in China than in the US.

The PPP measure has many uses, but assessing geopolitical power is not one of them. It is not helpful in answering the primary question that most commentators fixate on: how China’s economic size and power compare to America’s in the broader contest for global supremacy.

For that, a more relevant consideration is, for example, how much money China can contribute to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and other multilateral agencies, and how much voting power it should get in return. Another consideration is the view from other countries with rival claims in the South China Sea: how many ships can China buy, build, and deploy? For these and other geopolitical questions, it is more useful to rely on China’s GDP at current exchange rates. The issue isn’t how many haircuts Chinese consumers can buy, but what the RMB can buy on world markets.

To be sure, some point out that the IMF itself presents GDP in PPP terms for certain very limited purposes in its World Economic Outlook. But the IMF takes no stand on the question of which economy is bigger.

The closest it comes to offering an official position is with its formula guiding the assignment of quota shares to member countries. Here, the measurement of GDP is weighted, with 60 percent counted at market exchange rates and only 40 percent at PPP rates. (The GDP index accounts for half of the total formula; other measures, such as trade openness, comprise the other half.)

The IMF takes quota sizes seriously. If China were to attain a higher quota than the US, for example, the Fund’s Articles of Agreement would require it to move its headquarters from Washington, DC, to Beijing.

For now, China has far less clout than the US at the IMF. But under President Donald Trump, the US is surrendering its influence in multilateral organisations such as the World Trade Organization, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), and the World Health Organization (even in the midst of a pandemic). It should surprise no one that China is filling the vacuum.

The US does not lack the economic or financial power to sustain its 75-year leadership of the international order. But under Trump, it has forgotten why that leadership position is important, and is flushing its power, and its reputation, down the drain.

Related Articles: