While the Lao PDR government recently called for increased investment in agriculture to boost its export market, there are several issues that have to be tackled before foreign investors come knocking.

Speaking to local media earlier this week, Deputy Minister of Agriculture and Forestry, Dr Bounkhuang Khambounheuang, said Cuba and Indonesia expressed interest in importing 100,000 and one million tons of rice respectively, with Vietnam seeking to purchase 500,000 head of livestock.

The country, however, was unable to meet this demand.

Despite around 70 percent of Laotians working in the agricultural sector, subsistence farming is still the norm and traditional production methods do not produce enough to meet market demand. Many families struggle to even meet their own household food requirements – let alone having surplus for export – making malnutrition a critical issue.

Inefficient farm productivity means the agricultural sector contributed only 17.3 percent to the country’s gross domestic product (GDP) last year according to a report released last month by the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA), one of Lao PDR’s most important development partners.

While Lao PDR’s economy has surged by around seven percent over the past decade, making it among the fastest growing countries in ASEAN, its agricultural sector has grown at a rate of only three percent over the past two decades.

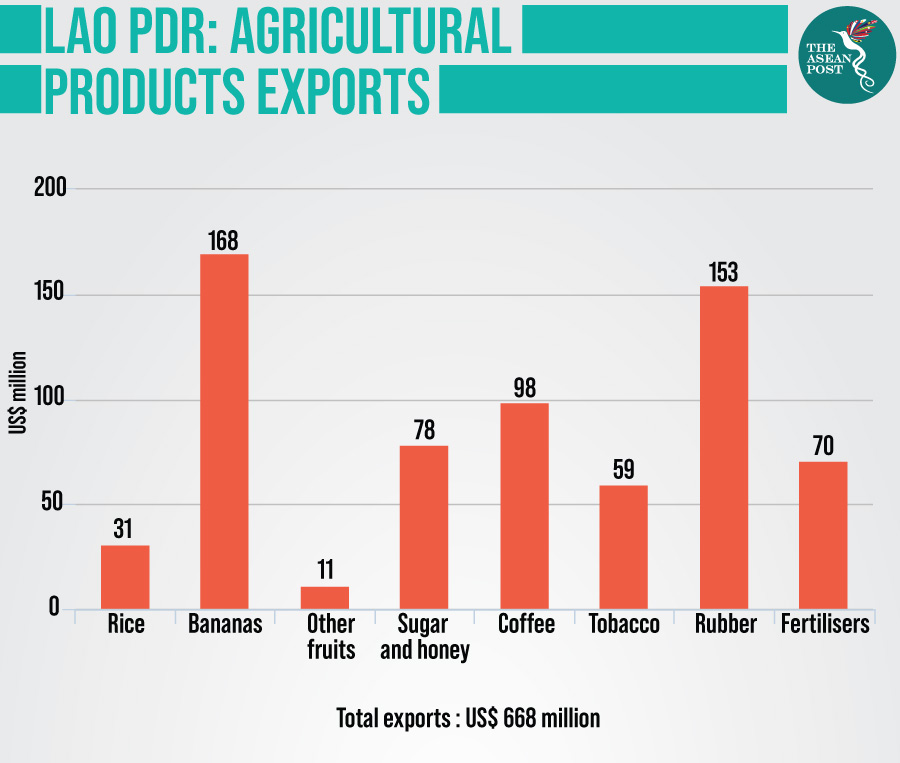

Apart from rice, which makes up half of the country’s agricultural output, Lao PDR’s other main trade crops include rubber, maize, coffee, bananas, citrus fruits and livestock.

According to the United Nations (UN) Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO), other threats to Lao PDR’s agricultural sector include poor on-farm crop storage, which leads to high levels of wastage and spoilage. In addition, poor crop handling practices mean that food safety is often compromised – which then has a negative effect on the country’s agricultural exports as more countries tighten restrictions on imported agricultural produce on health and safety grounds.

Climate change and the risk of natural disasters such as floods and drought has also put off investors.

Missing middle

In a report titled ‘Agriculture, Natural Resources, and Rural Development: Assessment, Strategy, and Road Map,’ published by the Asian Development Bank (ADB) in December, the Manila-headquartered regional bank stated that Lao PDR’s agriculture, natural resources, and rural development (ANRRD) sector is characterised by the lack of downstream enterprises, or as ADB calls it – the “missing middle”.

Characteristics of the country’s ANRRD sector include a relatively narrow range of productive outputs that involve small, fragmented production volumes, extremely short – mostly local – and seasonal market chains, and the high cost of freight.

“The missing middle reflects the commoditisation of commercial agriculture through external investment and control where regional enterprises directly contract land and manage the output from farm to border,” stated the report.

Chinese companies have been the biggest investors in Lao PDR, accounting for more than 77 percent of investment in 2017. While foreign direct investment (FDI) flow to Lao PDR has swelled from US$333 million in 2010 to US$1.7 billion in 2017 according to data from the ASEAN Secretariat and ASEAN FDI Database, infrastructure – primarily electricity generation – remains the largest recipient of FDI in the country. Agriculture, meanwhile, attracted US$184 million – or around 10 percent – of Lao PDR’s total FDI in 2017.

However, despite the official government line of welcoming FDI – several obstacles remain.

“The local free market economy combined with a strong communist state control mechanism makes FDI partially complex,” noted advisory and tax firm Dezan Shira & Associates in their 2019 investment outlook for Lao PDR.

“Requirement for foreign investors to comply with special rules – in particular concerning strategic areas like mining and hydropower where the government largely has to approve projects – increases the need to use a local partner while investing in large projects,” added the research note.

Legal uncertainty

Legal uncertainty – especially lack of transparency – deters investors. While many existing laws are unclear, if not contradictory, the 2016 Law on Investment Promotion clarified investment policies and introduced comprehensive tax incentives.

However, insecure land ownership and property rights has hampered investment in land and water resources. As the ADB pointed out, transferable titles or land use certificates can serve as collateral and facilitate access to finance, and their absence makes agricultural lending riskier to financial institutions. The absence of documented ownership means that the government can reallocate land to other users, with the risk of land loss undeniably making long-term investments less appealing.

A rice export ban in 2008 is another example of legal uncertainties in the agricultural sector. Introduced in 2008 in response to food price spikes, the ban compromised the country’s reputation as a reliable supply partner. While the ban has since been lifted, officials in some provinces continued to impose it until 2013 – apparently unaware of the policy shift.

It is only when such issues are addressed that private stakeholders will be ready to invest in Lao PDR’s agriculture, a sector which has significant potential to drive exports and serve as a source of inclusive economic growth.

Related articles: