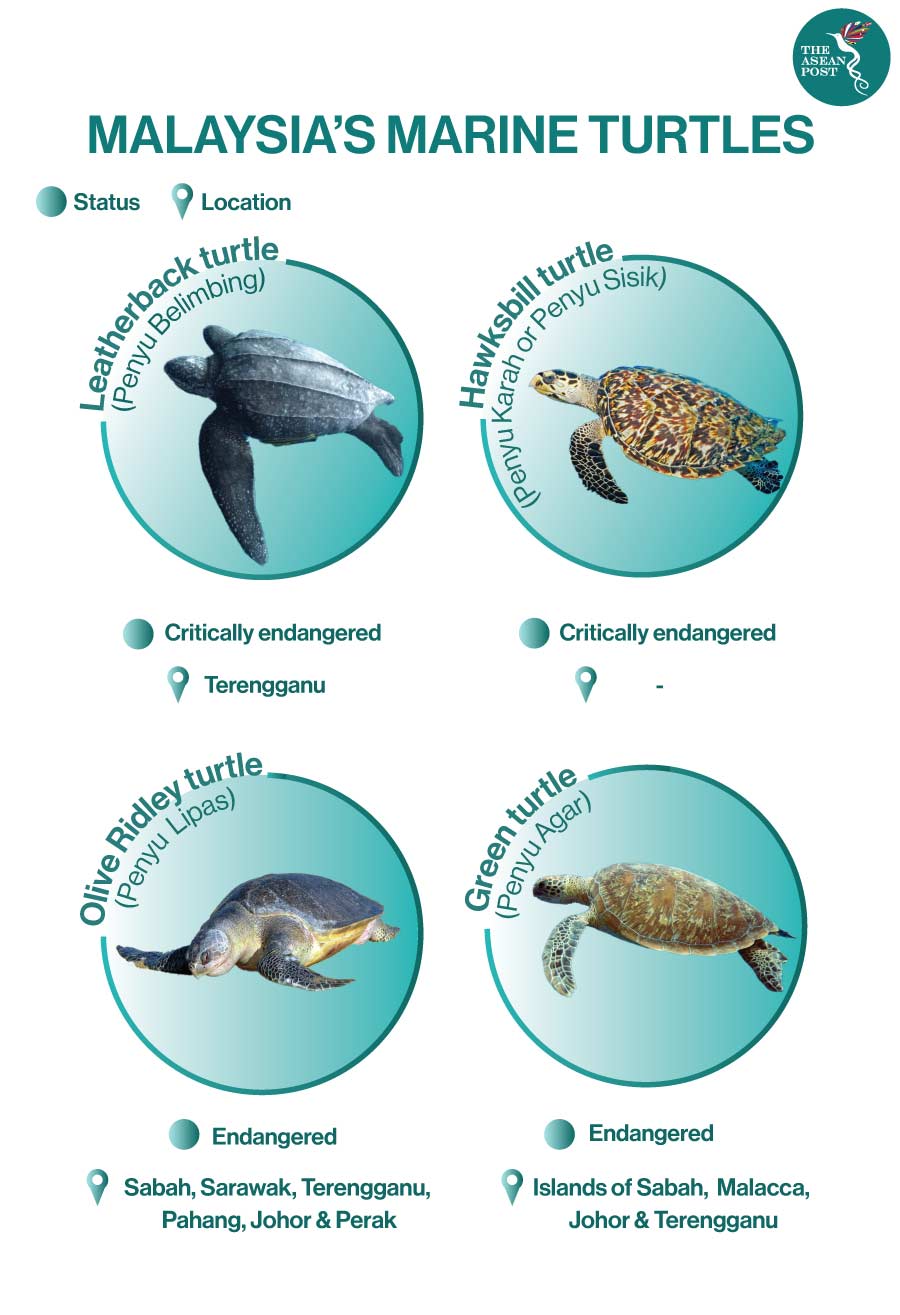

Malaysia is home to important habitats for marine turtles such as nesting beaches for the laying of eggs and coral reefs and seagrass beds as their feeding grounds. According to the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) Malaysia, the country hosts four out of the seven species of marine turtles found in the world, which are the green, hawksbill, olive ridley and leatherback.

Marine turtles are vital for ocean ecosystems. Green turtles graze on seagrass beds, which in turn, increases the productivity of the seagrass ecosystem, while hawksbill turtles feed on marine sponges to help maintain the health of coral reefs.

Unfortunately, human activities such as overexploitation of the reef area, pollution, ineffective governance and coastal development have made the nearshore ecosystem vulnerable to habitat change, deterring marine turtles from emerging ashore.

The status of marine turtles in Malaysia is either endangered or critically endangered. WWF Malaysia states that the leatherback turtle population in Malaysia has declined by more than 99 percent since the 1960s, while olive ridley turtles have declined by more than 95 percent. The once large populations of green turtles in the east coast state of Terengganu and the state of Sarawak in east Malaysia have decreased significantly since 1970.

Egg Poaching

Threats to sea turtles include egg poaching, trade and consumption. Monique Sumampouw, People and Marine Biodiversity Manager of WWF Malaysia said: “Sale and consumption of eggs of all species are banned in Sabah and Sarawak. However, there is no similar ban in Peninsular Malaysia, with the exception of leatherback turtle eggs. Instead, egg collection for incubation is regulated by government-run licensing systems.”

This lack of a nationwide turtle egg ban puts marine turtle populations further at risk. Terengganu, an east coast state without an egg ban, once hosted one of the world’s largest nesting grounds of leatherback turtles, with 10,000 annual nestings in the early 1950s. Five decades later in 2006, not a single nesting was recorded. In 2017, the Department of Fisheries only recorded two nests.

The illegal turtle egg trade in West Malaysia continues to threaten the majestic sea creature’s population. In July 2019, marine police seized 250 turtle eggs from the Lahad Datu wet market, worth RM500 (US$120) and in September 2019, the Sarawak Forestry Corporation (SFC) enforcement team nabbed two men in possession of 600 turtle eggs with the intention to sell at a market.

Floating Threats

Marine turtles are also dying as they sometimes consume floating plastic bags, mistaking them for jellyfish. The increase in plastic debris in the ocean has posed major concerns for sea creatures. It is estimated that over one million marine animals, including mammals, fish, sharks, turtles, and birds, are killed each year due to plastic debris according to Sea Turtle Conservancy, the world’s oldest sea turtle research and conservation group.

Plastic particles or microplastics can be found everywhere, but mostly in sediments. If sea turtles feed on these particles, they can become sick or even starve to death. Juara Turtle Project (JTP), a turtle conservation project run by the Fisheries Department of Malaysia (FDM), found a juvenile green turtle in 2017 with its stomach contents mainly composed of string and fishing line pieces, foam pieces and microplastics.

Detrimental fishing methods using gear such as trawls, long lines and ray nets are also harmful to turtles as they tend to get caught in them. In September 2019, a turtle was found tangled in a large ghost net on a Malaysian beach. Ghost nets are fishing nets that have been abandoned and discarded in the ocean.

Coastal Reclamations

Coastal reclamations have also significantly damaged marine turtle populations. Reclamation projects in Malaysia can be found in the states of Kedah, Penang, Perak, Melaka, Pahang, Kelantan and Johor. According to Lau Min, WWF conservation manager for turtles in peninsular Malaysia, land reclamation projects have reduced landings in certain beaches by up to 70 percent.

In the state of Malacca, coastal reclamation projects have been known to affect the nesting grounds of hawksbill turtles. The state began reclamation in the 1970s, but the recent pace of development has introduced new concerns over the project’s environmental impact. In Pulau Upeh, there was a drop in turtle landings from 111 in 2011 to a mere 36 in 2017 and only 20 landings in 2018.

Chairman of the state Agriculture, Entrepreneur Development and Agro-based committee, Norhizam Hassan Baktee said that the state government realised the critically endangered hawksbill turtles could be driven to extinction by land reclamation along the Malacca coastline.

In a recent move to conserve and preserve the turtle landing sites, the state has cut back on the perimeter of ongoing reclamation works close to Pulau Upeh. “We have stopped contractors from encroaching the perimeter of the permitted reclamation zone,” said Norhizam.

Up north, the Penang state government’s plans to create three massive artificial islands on the southern coast of Penang island continues to face opposition by activists and netizens alike. Reclamation work for the project will affect the landings of olive ridley turtles which migrate thousands of kilometres around the Indian Ocean between their feeding and nesting sites. It is the smallest and most rarely sighted marine turtle found in Malaysian waters.

Though there are many ways for Malaysia to protect its marine turtles, the conservation of the country’s biodiversity and environment remain critical if these endangered creatures are to enjoy a sustainable future.

Articles selected as Top Stories of 2020 are those that were the most popular among readers of The ASEAN Post for the month in question.

Related Articles: