On 24 March this year, at long last, Thais will finally be able to head to the polls to elect a government after more than four years of military rule.

The current ruling military junta – also known as the National Council for Peace and Order (NPCO) led by Prayut Chan-o-cha came into power in 2014 after it carried out a coup against the then caretaker government led by Yingluck Shinawatra. Ever since seizing power, the military junta promised to return the country to proper democracy. After four years of false promises and delays, the elections slated for March looks certain to happen.

While most Thais may be happy that the country will finally be handed back to a democratically elected government, many are also questioning the fairness of the upcoming elections. The actions of the junta in the past do not exactly inspire confidence among certain Thai voters that the elections will be free and fair.

Social media clampdown

A particular concern is the clampdown on social media. After the announcement of the elections, the Thai election commission released strict guidelines for election campaigning. According to local reports, strict rules have been imposed on social media. The commission has apparently banned social media posts by parties that contain information other than the candidates’ names, pictures and biographies, and the party name, logo policies and slogans. Some have argued that this could be a deliberate move to stifle parties that rely heavily on social media.

The Guardian reported that Sudarat Keyuraphan, head of election strategy for the Pheu Thai party had deactivated her Facebook account in an apparent move to avoid any violations. She was followed by several other political candidates.

The ASEAN Parliamentarians for Human Rights (APHR) pointed out that the military junta is known to use a range of repressive laws, including the Computer Crimes Act, the lèse majesté law, and sections of the Criminal Code to silence individuals.

“[T]he climate in the country is still not conducive for a free and fair election – the junta must now remove all remaining draconian limits on freedom of expression. Unless political parties are allowed to campaign without fear of retaliation, voters will not be able exercise their democratic right and make an informed choice at the ballot box,” said Charles Santiago, Chair of ASEAN Parliamentarians for Human Rights and a sitting member of parliament (MP) from Malaysia.

Source: Bloomberg

Source: Bloomberg

Unfair advantage

Others have argued that Prayut and his cohorts have had a head start to the elections. When the 2014 coup happened, the military banned all political activity including campaigning under the guise of “stability”. However, while opposition parties were banned from carrying out activities in public, Prayut was reported as going around the country campaigning.

There have also been accusations of gerrymandering against the election commission. In November, the election commission released new voting divisions which some say allegedly favour pro-junta parties.

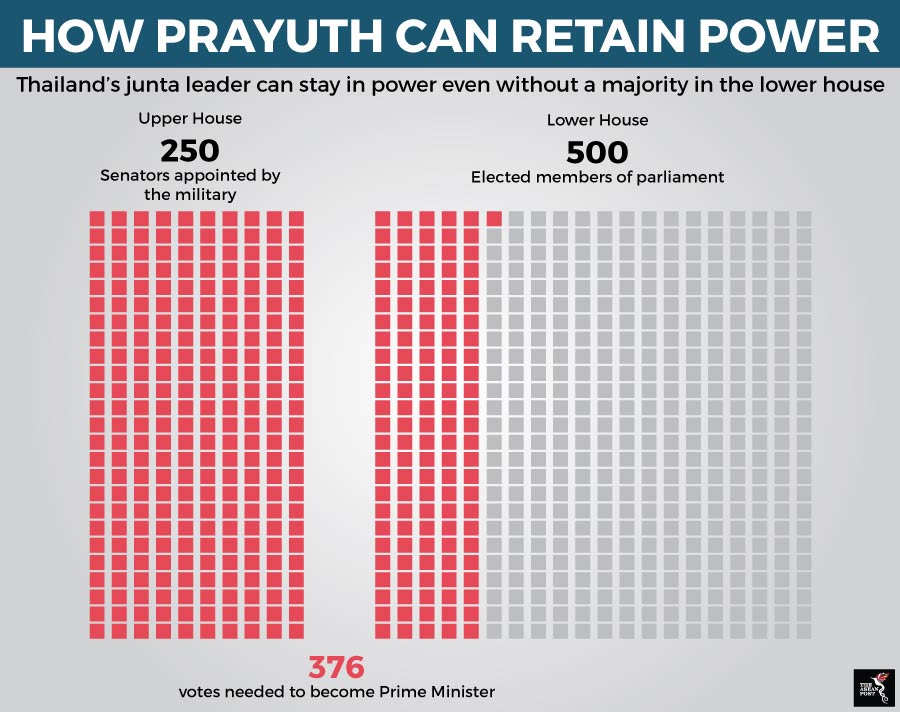

If the opposition parties manage to win the elections despite these challenges, they would then have trouble appointing one of their own as Prime Minister. Under the new constitution drafted by the junta and approved in a referendum in 2016, the 250-member upper house or Senate must comprise of military appointees. In electing a new Prime Minister, both houses – the 250-member upper house and the 500-member lower house – can vote for their leader. Hence, for Prayut to remain in power, all he needs is for his 250 military appointees to back him as well as 126 votes in the lower house to form a simple majority in his favour.

With such imbalances, the military’s desire to stay in power could prove dangerous. Should the lower house go to the opposition but Prayut retains his position as Prime Minister after the elections, chaos could ensue. He would likely have to deal with an uncontrollable lower house and a dissatisfied populace, both of which could spell the return of instability that has long haunted Thai politics.

Related articles: