In the city of Monessen, Pennsylvania, then presumptive US Presidential candidate, Donald Trump took to the stage to address a crowd of supporters.

“Today, I am going to talk about how to Make America Wealthy Again,” he began.

Trump then continued his barrage of outrage and criticisms towards the elites who have been exporting jobs from the US and stifling the American middle class. His speech culminated to the unveiling of his own plan to bring jobs back to the country.

His first step, pry the US away from the “disastrous” TPP (Trans-Pacific Partnership) agreement.

“There is no way to “fix” the TPP. We need bilateral trade deals. We do not need to enter into another massive international agreement that ties us up and binds us down,” he explained.

“I am going to withdraw the United States from the Trans-Pacific Partnership, which has not yet been ratified,” he then announced to the rousing applause from his staunch following.

His words that afternoon marked the beginning of the end for US involvement in the TPP. Upon election as President of the United States, Trump delivered his promise from the Oval Office – his signature on the memorandum, officially ended US participation in the trade agreement.

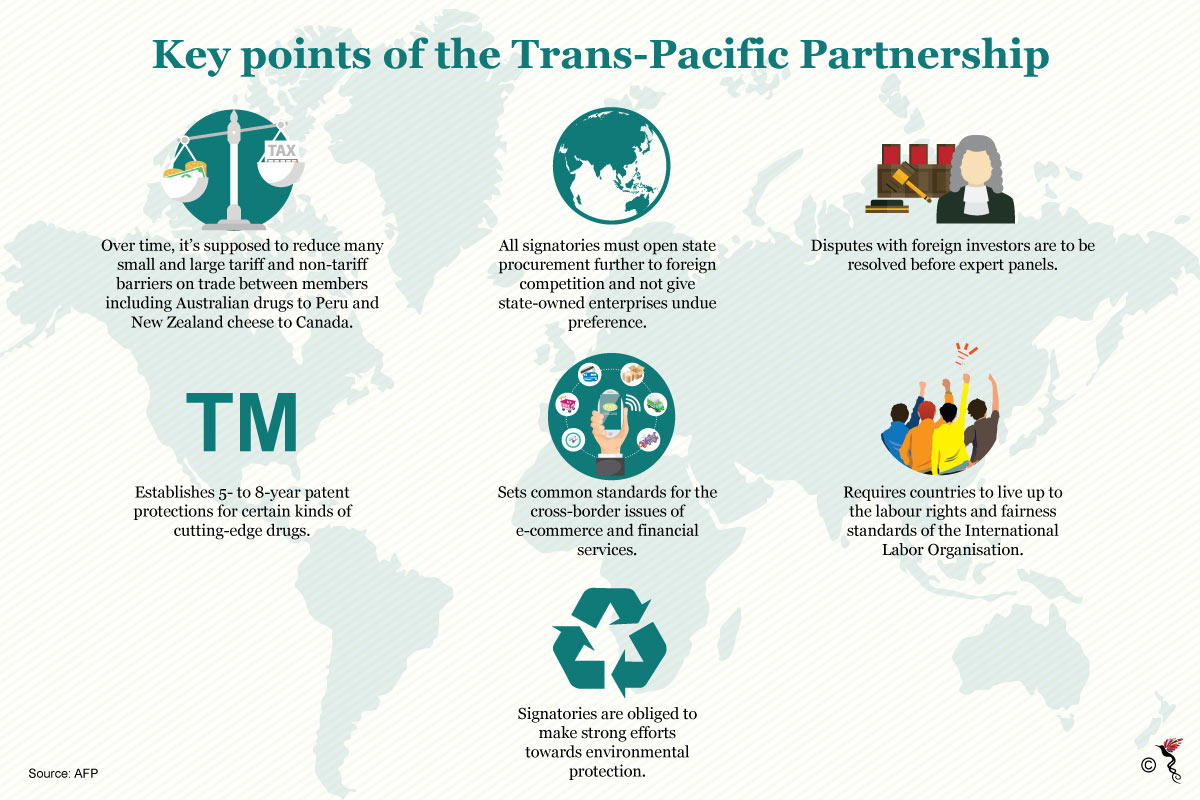

Key points of the Trans-Pacific Partnership. Source: AFP (Agence France-Presse).

A relic from the Obama administration

Trump’s motivations are not necessarily founded on his rhetoric to “bring jobs back to America”. As much as he mouths that at every rally or meeting, it is widely known that he is hellbent on undoing any efforts made by his predecessor.

“Indeed, he’s demonstrated an almost a pathological drive to eradicate anything associated with Obama, even if the alternatives might be worse. Numerous examples of this approach to governance can be found in Trump’s domestic and international policymaking since taking office,” Executive Director at the ICAPS (International Center for Advanced Political Studies), Josef Gregory Mahoney told The ASEAN Post.

The TPP had been a landmark trade deal initiated by former US president, Barack Obama as part of his “Pivot to Asia” foreign policy. It is held by many as a move to ensure countries within the region remained within the American orbit given the rise of China as an economic powerhouse.

Trump’s withdrawal from the accord has sent alarm bells ringing in Washington of a possible usurpation of American hegemony in East Asia by Beijing. After all, China has not kept mum on its own grandiose BRI (Belt Road Initiative) vision which encompasses 65 countries across three continents including Asia. An absence marked by the US pulling out of the TPP could disrupt the delicate Sino-US balance in the region.

China's vision of a land and sea-based trading network under the BRI (Belt and Road Initiative).

Beaten but not broken

Trump’s revocation of the pact has not fully stopped the remaining 11 countries from going through with it. However, the TPP is not without its challenges.

For starters, the current rules for the accord to come into effect would require at least six signatories to have successfully ratified the agreement. Of those signatories, the six must represent 85 percent of the total GDP (gross domestic product) of all signatories. Given that the US represents 62 percent of the GDP of the signatories, its departure means that it is now impossible for the TPP to come into effect under current stipulations.

Japan now informally leads subsequent rounds of TPP negotiations. In one such meeting last month, the negotiators decided on a November 2017 deadline to clinch a new deal. Nevertheless, a full-fledged agreement is hardly a realistic ambition to aim for within the timeframe and is also dependent on Japan's domestic politics.

“I’m not entirely sure that the 11 countries will be able to ratify the TPP agreement. This may depend on the outcome of the elections in Japan. If Abe gets a strong mandate, he may push ahead with it,” said Co-Coordinator of the Regional Economics Studies Programme, ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute, Cassey Lee.

As attempts to salvage the TPP continue, Japan is still counting on a sliver of hope that the US might reverse its decision to pull out of the trade pact.

In May this year, Japanese President, Shinzo Abe was asked if the goal of Japan’s leadership vis-à-vis the TPP negotiations is to bring the US back into the fold of the agreement.

“Since the US understands the importance of having free and fair rules in the trading world, our wish is that the US will return to TPP,” Abe replied.

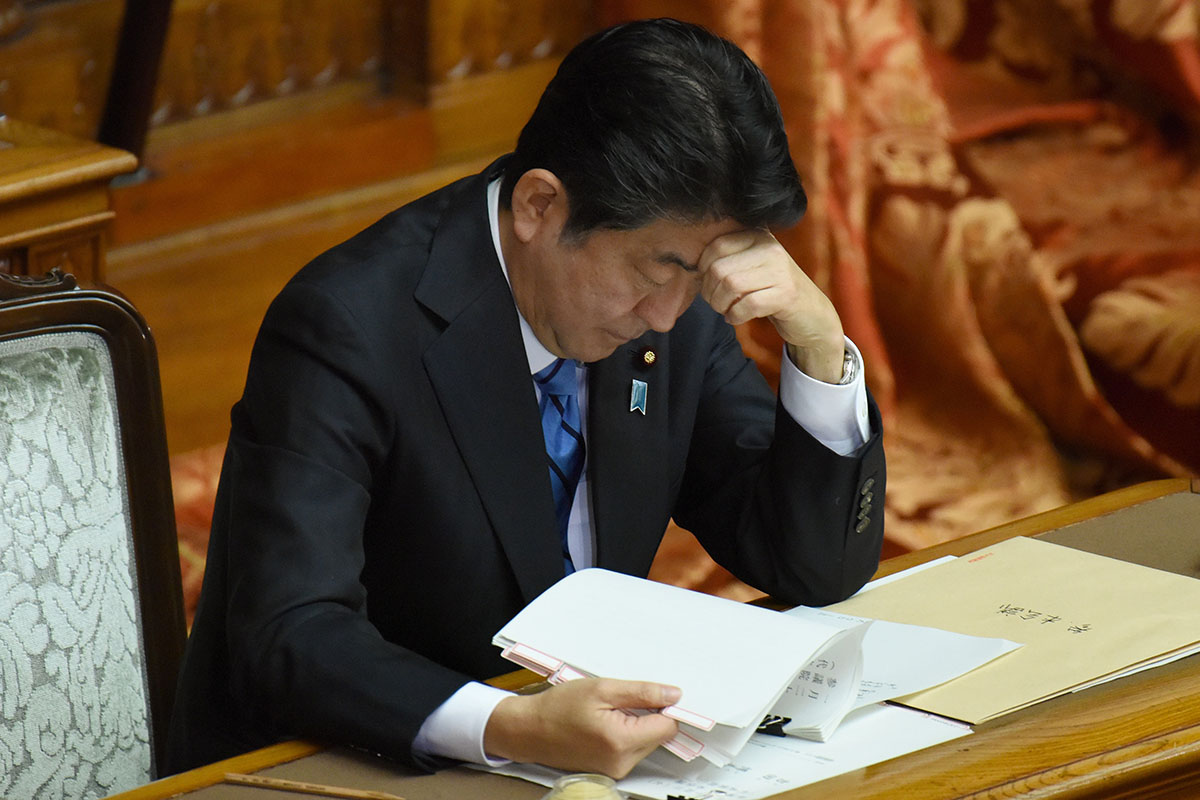

Japan's Prime Minister Shinzo Abe listens to questions at his seat during a plenary session of the upper house of parliament in Tokyo on January 24, 2017, after US President Donald Trump decided to pull the US out of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). (AFP Photo/Toru Yamanaka)

Echoing his sentiments Japanese chief negotiator for the TPP, Kazuyoshi Umemoto told reporters last month that “we would like the US to come back as soon as possible, which would mean the original TPP would have to be ratified.”

Will leaving the backdoor open work?

Resident Senior Fellow at the Institute of China American Studies, Sourabh Gupta, however, believes that the possibility of the US re-joining the TPP is slim and almost non-existent.

“The pro-trade consensus in the US is slowly breaking down and though it is hard to say what it will look like in 4-5 years, the receptivity towards international trade openness will be less, not more, within the US political system in the years ahead,” the senior international relations policy analyst told The ASEAN Post.

Besides that, the US is busy in its renegotiations regarding NAFTA (North American Free Trade Agreement) which could complicate a re-entry into the TPP.

“Some critical elements that are part of the NAFTA re-negotiation – if successful, such as auto and textile rules-of-origin, will also thereafter have to be re-negotiated if U.S. is to re-enter TPP. And these were difficult areas of negotiation in the original TPP and will be even harder in a re-negotiated TPP,” Gupta remarked.

Mahoney, who is also a Professor of Politics at East China Normal University holds an opposing view – believing that Trump himself might change his mind if the TPP was rebranded to shake off any reminders that it was initially Obama’s effort.

“Trump has repeatedly demonstrated that he is more anti-Obama than a partisan ideologue. If TPP were to change its name and offer even superficially better terms to the US, with concessions that can be spun as protecting jobs, then Trump might be enticed back into it,” he said.

This would in turn, validate the expediated efforts by Japan to ink a deal by end this year, provided if the US follows a “if you build it, then they will come” strategy. However, whether this can be accomplished by the November deadline remains to be seen.

Lee similarly echoed Mahoney’s sentiments but he believes that the the US will only rejoin after the Trump administration has expired. He also noted that many amongst the TPP-11 are keen on the US getting back into the pact partly because they lack FTAs (Free Trade Agreement) with the superpower.

Mahoney also warned that the vacuum left by Washington leaves space for Beijing to capitalise with, using the RCEP (Regional Comprehensive Partnership Agreement).

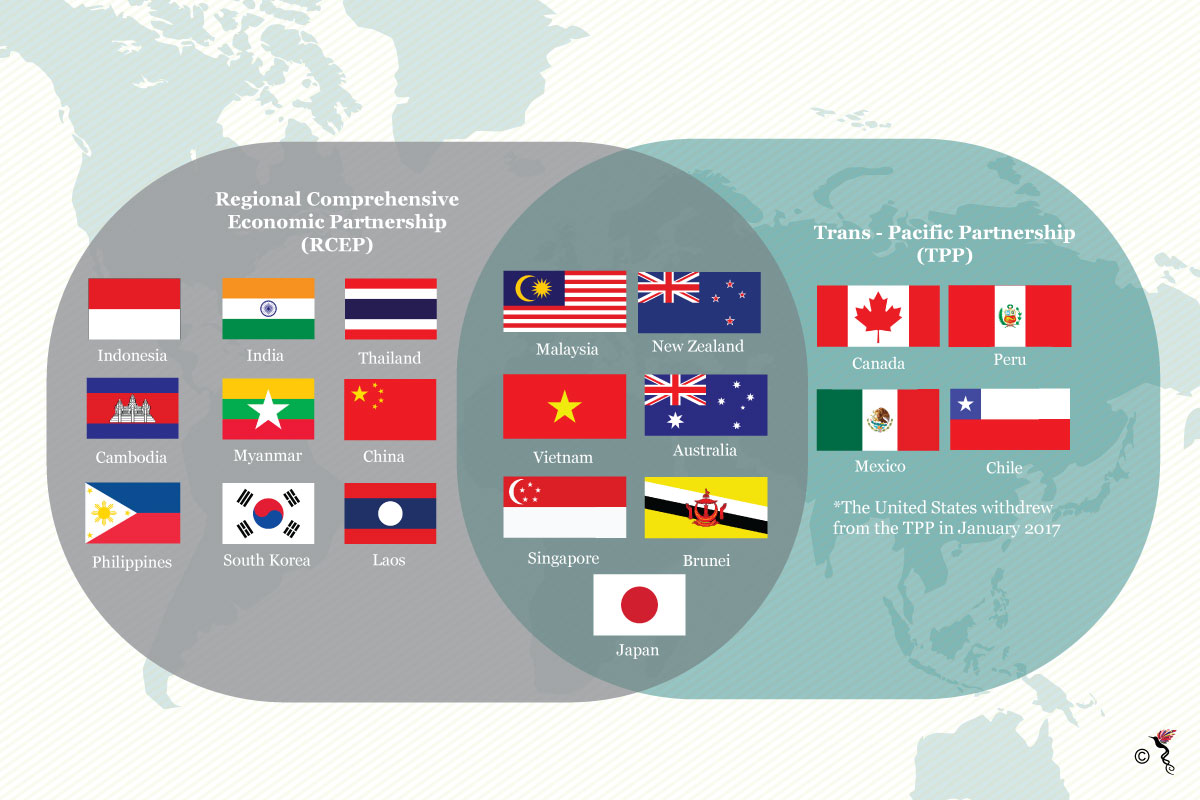

Involvement of countries in the TPP and RCEP trade deals.

“The TPP traded, to some extent, economic benefits for political ones. Therefore, without the US, perhaps TPP’s major strategic benefit has evaporated. This in turn feeds RCEP,” he said.

RCEP, although officially led by ASEAN in an attempt to strengthen the 10-member association’s regional FTAs is still a useful tool for Beijing to achieve its BRI Initiative.

“The risk to the US and TPP is that even if Trump or his successor chooses to return to TPP in whatever form, it may well be too late to counter both political and economic inroads made by RCEP in the meantime, particularly as potential synergies emerge via the BRI or AIIB (Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank),” Mahoney remarked.

Deal or no deal?

The Trump administration’s policy towards the East Asian region remains to be set in stone. Thus far, several indicators like his rescindment from the TPP and bilateral meetings with ASEAN leaders give a slight inclination to Washington’s foreign policy posture.

Senior Advisor and Senior Director of the Asia Pacific Security Programme at the Centre for New American Studies, Patrick Cronin noted in a conference in Kuala Lumpur recently that the US “has not veered into isolationism”. However, he relented that there is yet to be “a sustained, consistent case for an affirmative, reliable commitment to the region.”

We might find an answer to Trump’s foreign policy for the East Asian region when he makes his five-nation trip to the Asia Pacific region in November. One of the five countries he would be visiting is Vietnam, who would be hosting the APEC (Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation Summit). It is at the side-lines of the APEC Summit that the TPP-11 are looking to hopefully smoothen out the remaining details of a salvaged trade deal.

The same deal, Trump’s country was once a pivotal part of.

Oh, the brutal irony!