The idea of breakthrough cases is not a new concept. With COVID, these infections are not a reason to turn down the offer of a vaccine.

As the pandemic rages on, new buzzwords and phrases find their way into our daily vernacular – and one that is currently doing the rounds is “breakthrough infection”.

This term refers to COVID-19 infections that occur more than 14 days after someone has been fully vaccinated; it does not refer to the severity of illness suffered from the disease but implies that a person has tested positive for the virus.

On the surface of it, this may appear rather worrying – but do not forget the purpose of the COVID vaccines is not to make you immune to the virus (they never claimed to do that), but to protect those vaccinated from severe illness and hospitalisation should they contract the virus.

Since no COVID vaccine is 100 percent effective, some infections in fully vaccinated individuals are expected. However, these appear to be uncommon, and a high proportion may be asymptomatic.

Generally speaking, those who have been fully vaccinated may still pick up the virus, but the immune response triggered by the vaccines means they are only likely to have mild if any symptoms at all.

For instance, in an American study looking at military personnel who had been fully vaccinated and got breakthrough infections, none of them needed hospital treatment.

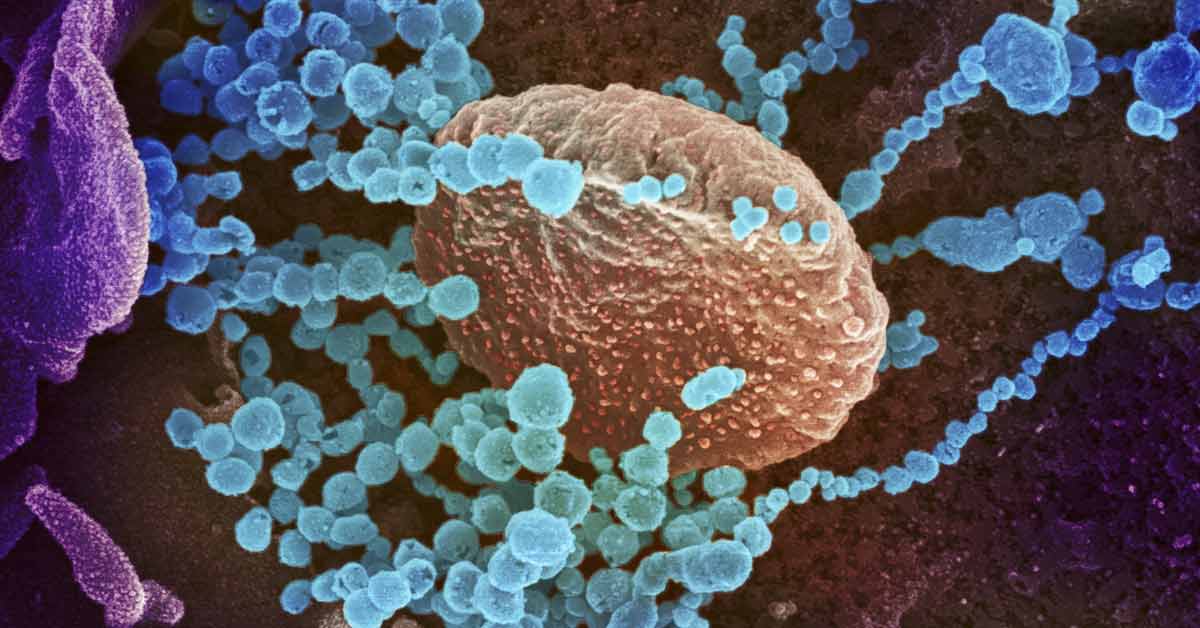

People who become infected with SARS-CoV-2 after being vaccinated against it are likely to have milder and shorter illnesses. This is because their immune systems have been primed by the vaccine to recognise the coronavirus that causes COVID-19 and to destroy it and any cells it has managed to invade before it has a chance to make them unwell – even though they can still test positive for the virus.

Prior to the emergence of the Delta variant, it was thought that those who were fully vaccinated were less likely to pass the virus on to others as they had lower “viral loads” – this refers to the amount of virus a person is carrying; the higher the amount of virus or “viral load” the more infectious the person is.

However, whether or not this is still true when it comes to the Delta variant is under review, but it is likely that even with Delta, breakthrough infections are likely to be milder in those vaccinated than those unvaccinated.

We are likely seeing an increase in breakthrough infections because fully vaccinated people are able to mix more as restrictions across countries with high vaccination rates ease. It is thought that the vaccines trigger less of a robust response in older people, thus we are seeing larger proportions of breakthrough infections in those aged 65 and over.

Having a weakened immune system may also increase the risk of getting a breakthrough infection, despite being fully vaccinated – such as those who are on treatment for cancer and those who are on medication that dampens down their immune systems because of other underlying health conditions.

The emergence of the Delta variant has also increased the risk of breakthrough infections as both the mRNA vaccines (Pfizer and Moderna) and the AstraZeneca vaccine are less effective against Delta when compared with the “wild” or original variant and the Alpha variant.

The fact that there are still high levels of coronavirus circulating in the general population means a higher chance of those fully vaccinated coming into contact with it and getting a breakthrough infection, albeit with milder symptoms.

But it is important to note that the idea of breakthrough infections is not a new concept, and in relation to COVID-19, these infections are certainly not a reason to turn down the offer of a vaccine.

We see breakthrough infections in many other diseases we vaccinate against because no vaccine is 100 percent effective. The gold standard of vaccines is the mighty MMR vaccine (measles, mumps, rubella). Two doses of MMR vaccine are 97 percent effective against measles and 88 percent effective against mumps.

This means about three out of 100 people who get two doses of the MMR vaccine will get measles if exposed to the virus. However, they are more likely to have a milder illness and are also less likely to spread the disease to other people. The fact that so many people are vaccinated against measles reduces the risk of breakthrough infections.

Mumps outbreaks can still occur in highly vaccinated communities, particularly in settings where people have close, prolonged contact, such as universities and close-knit communities.

Breakthrough infections are even more likely with the seasonal flu virus even in those vaccinated against it – flu vaccine efficacy rates vary from year to year depending on the strains they are targeting that year but they generally vary from 40-60 percent – meaning breakthrough infections are relatively common.

Groups and individuals who are opposed to the idea of COVID vaccines point to breakthrough infections as another reason not to get vaccinated, but that argument is specious. The vaccines were never about 100 percent protection from the virus; no vaccine can boast that efficacy.

They have always been about reducing the severity of symptoms, and significantly lowering the risk of needing hospitalisation from COVID – and they are still excellent at doing this even with the highly transmissible Delta variant to contend with.

Breakthrough infections remain a reality for all diseases that we have vaccinated against, the key is getting enough of the world vaccinated to help reduce the number of breakthrough infections and protect the most vulnerable in society.

That has been the mantra for all vaccination programmes that have come before and is still the mantra for the COVID vaccination programme. – Al Jazeera