The news of an impending acquisition by Grab of Uber's Southeast Asian business is now drawing the scrutiny of Southeast Asian regulators. Their concern is that a monopoly on ride-hailing services would hurt instead of benefit consumers in the long run.

According to reporting by the Wall Street Journal, Uber is said to have agreed to sell most of its Southeast Asian operations to Grab, in exchange for between 20-30% of Grab’s equity. The exact size of the stake has not been finalised as yet and the finer details of the deal are still being ironed out. The deal is also likely to be subjected to regulatory scrutiny first.

Such a review is likely since the deal would effectively make Grab a monopoly for ride-hailing services in the region. Grab currently serves 178 cities across Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia, the Philippines, Thailand, Vietnam, Myanmar and Cambodia.

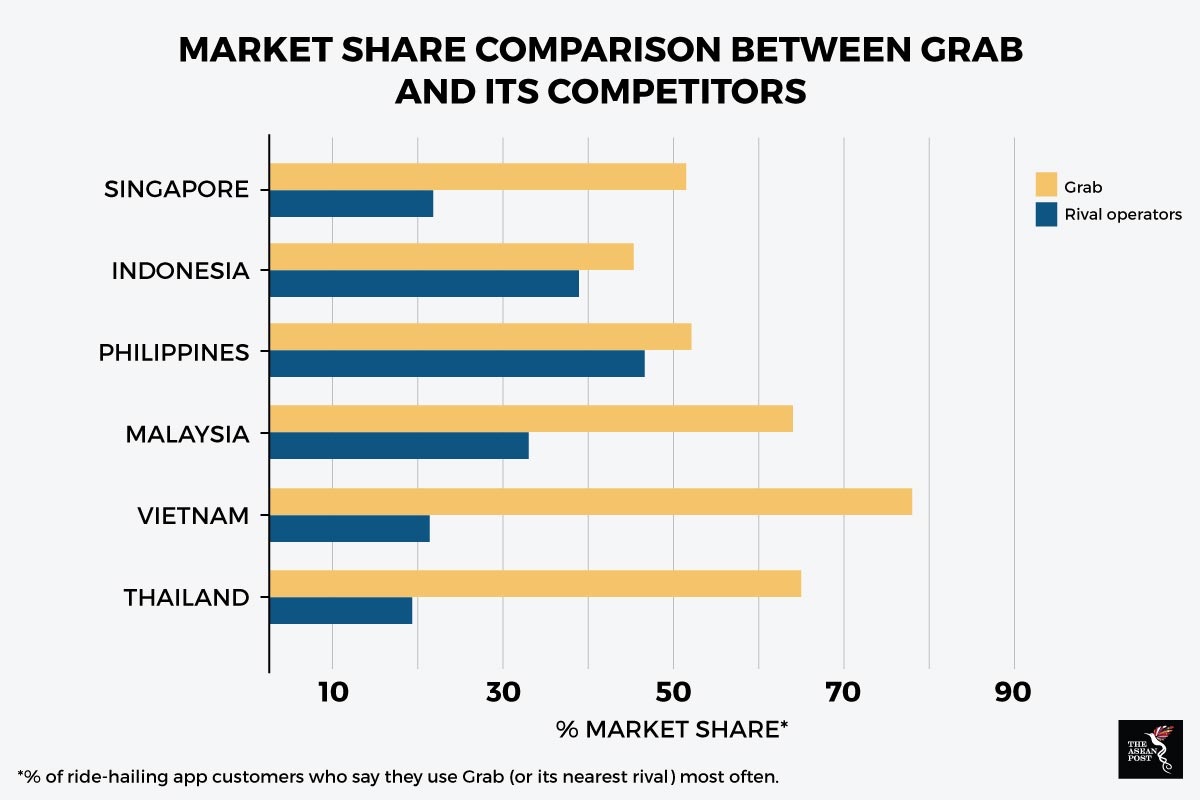

"We already hold three quarters of market share, so it's not big on our radar," commented Sean Goh, country head of Grab Malaysia to The Malaysian Reserve this month. Southeast Asia represents a market size opportunity of about 620 million people.

Singapore regulators, for one, are concerned about the degree of transparency Grab’s pricing mechanisms might have in the near future. Reviews were likely to be conducted on point-to-point transport in order to prevent dominance by any one player, Ng Chee Meng, Singapore’s Second Transport Minister said during a parliamentary debate.

Source: Grab & Bloomberg, 2017

“It is entirely conceivable that in the future they can charge different people different prices,” Dr Walter Theseira, a transport economist with the Singapore University of Social Sciences told Singaporean publication Today, in March 2018. He added that in order to determine the fairness of pricing policies in place, more information about Grab’s business practices would be needed to enable Singapore’s Transport Ministry to review the deal better.

Transparent pricing aside, ride-hailing customers are already the most likely losers in the event of a monopoly. Customer discounts, for one, could become a thing of the past once there is no longer any prize to vie for. Customers of China's Didi Chuxing experienced a similar predicament when Didi bought over Uber’s China operations back in 2016 following the company’s poor performance there. After the buyout, not only did Didi cut down on customer discounts, it also took away drivers’ bonuses.

Grab was last valued at US$6 billion according to reporting by Bloomberg. Its rapid expansion within the region has been due in part to the strategy of localising its services as much as possible. It applies local language functionality to its apps in different countries and varies its service offerings in different regions. Grab’s services have also expanded beyond car ride-hailing to include bike ride hailing, food delivery and digital payments, since it was set up in 2012.

Uber, on the other hand, first entered the Southeast Asian market with a one-app fits all design which did not quite fit the region’s immediate needs. For one thing, it forced credit card payments on a market that preferred to use cash. It also positioned itself as a pricier option compared to taxi alternatives. The result is that despite numerous capital injections, Uber has only been trailing behind Grab in Southeast Asia. In 2017, Uber reported a net loss of US$4.46 billion, citing unfavourable market conditions as the reason behind its lack of momentum here.

"The economics of the market are not what we want them to be," Dara Khosrowshahi, Uber’s Chief Executive said while paying a visit to New Delhi in February 2018.

“We expect to lose money in Southeast Asia and expect to invest aggressively in terms of marketing subsidies,” he told reporters at the time.

Government regulation will likely be a determinative factor in whether or not Grab would form a monopoly in the region. Ng further said during the parliamentary debate that Singapore’s review of the deal would also likely include a re-evaluation of how ride-hailing firms are licensed, and how the industry is structured. Regulation had thus far been minimal in order to encourage innovation in the field.

On a local level, Southeast Asian governments would need to manage this balance carefully, so as to encourage more players in the market while simultaneously regulating the expansion of existing players. For now, national regulators are likely to have the biggest say in maintaining a healthy and competitive ride-hailing market in the region.