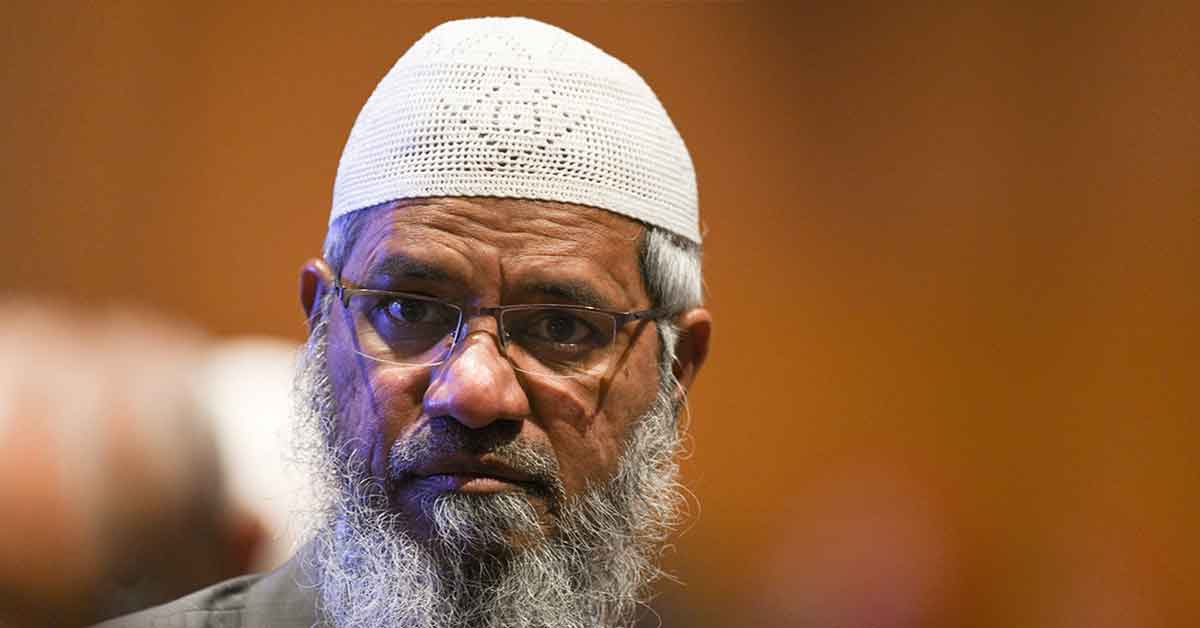

According to local newspapers in the subcontinent, India sent a formal request on 14 May, 2020 to the Malaysian government for the extradition of the controversial Islamic televangelist, Dr Zakir Naik, who has been living in the ASEAN member state since 2017 after he was granted permanent resident status there.

The Indian government's latest move came after the change of guard at Putrajaya, Malaysia's administrative capital, in the hope that the United Malays National Organisation (UMNO) and Malaysian Islamic Party (PAS)-backed National Alliance (Perikatan Nasional) coalition government of Prime Minister Muhyiddin Yassin might rethink its stand on the fugitive preacher and try to mend ties with India, which had greatly suffered due to former prime minister Dr Mahathir Mohamad's remarks on the abolition of Article 370 in Jammu and Kashmir and the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA). India, in retaliation, had imposed curbs on the import of palm oil from Malaysia.

Even though Malaysia and India had signed an extradition treaty in 2010, it's highly unlikely that the New Delhi request will make any headway as Dr Naik has become a populist tool to woo Malay Muslims due to his popularity among them as they constitute more than 60 percent of the country's population. During the 2014 general election both, former prime minister Najib Razak and his successor, Dr Mahathir, had used the popularity of the controversial preacher to bolster their support base among the Malays.

Ironically, in ethnically-divided Malaysia, an Indian national has become the biggest unifying factor among the Malays, who were greatly split during the 2014 general election.

Dr Mahathir had his own reasons for taking a tough stand on India and refusing to extradite Dr Naik. Dr Mahathir's Pakatan Harapan (Coalition of Hope) government at the time was seen by Malays as being anti-Malay and anti-Islam because they felt that it was controlled by the Democratic Action Party (DAP), which is dominated by ethnic Chinese Malaysians. What made matters worse was the DAP's very vocal and open opposition of Dr Naik's presence in Malaysia and on many occasions, the party had even questioned its own government's decision not to extradite him to India.

To remove this perception, Dr Mahathir was forced to take this stand and refused to extradite Dr Naik despite his provocative remarks against Malaysian Indians and Chinese.

Islamophobia In India

Dr Naik, who preaches a hard-line Wahhabi strand of Islam, has been very popular among Islamist groups and parties, including PAS, which is part of the current ruling coalition.

A senior Kuala Lumpur-based journalist, who does not want to be named, says that apart from appeasing the majority Malays, the sharp surge in Islamophobia in India has made it impossible for any Malaysian government to hand over Dr Naik to India as Malays feel that he will not get a fair trial in India, currently ruled by the Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) government, which does not hide its antipathy towards Muslims. This perception has been further enforced by the recent virulent campaign by the Indian media, blaming Muslims for the spread of the coronavirus.

"Given these circumstances, handing over Dr Naik to India will be seen as a great betrayal. Many political analysts and leaders have already warned of dire consequences should Malaysia accede to India's request. Malaysia, being a Muslim-majority country, will be seen as a country which failed to protect a fellow Muslim," he explained.

It must be noted that it was PAS that had urged Dr Mahathir to ignore India's request, saying that the charges against Dr Naik in India are aimed at "blocking his influence and efforts to spread religious awareness among the international community".

“Now, that PAS has four ministers in the present government, do you think that Prime Minister Muhyiddin Yassin has the political will or strength to overrule them?” he asked.

Moreover, since the fall of Dr Mahathir's government, the political dynamics have changed in the country and the ruling coalition is back to wooing the majority Malays. Surprisingly (or not), Dr Naik has emerged as one of the biggest cohesive factors.

The presence of someone as divisive as Dr Naik would be a headache for a government of any colour or hue, more so in Malaysia where the preacher’s controversial sermons do not sit well with the country’s ethnic minority Indian and Chinese communities. Many of them are quite uncomfortable as they fear that his presence may further fray the simmering racial tensions in the country.

Outside The Malaysian Context

Malaysian politicians and human rights activists started raising their voices against Dr Naik when it emerged in 2016 that two of the militants, who stormed a Dhaka cafe in which 22 people were killed, had been "inspired by his preaching". At the time, the Barisan Nasional (National Front) government led by Najib Razak was in power and for the first time in the Malaysian political history its two major coalition partners – the Malaysian Chinese Association (MCA) and Malaysian Indian Congress (MIC) – questioned their government's continued support for Dr Naik as they felt that the controversial Islamic preacher's presence in Malaysia was detrimental to society.

The then health minister in Najib Razak’s government and MIC president, Dr S Subramaniam, was the first to express his disagreement over Dr Naik's stay in Malaysia and said that his activities in the country “are outside the Malaysian context”.

In March, 2017 a group of 19 human rights activists filed a civil suit against the Malaysian government, accusing it of failing to protect the country from the controversial televangelist.

Dennis Ignatius, a former Malaysian diplomat, says Naik's case is not about the legalities of extradition but local politics and religious sentiment. Having taken a careful measure of Malaysia's fractured political and religious landscape, Dr Naik has skilfully played-off one segment of Malaysia's population against another to stave off extradition.

By conveniently insisting that he is a victim of religious persecution, he obliges local Muslims to come to his defence. It is a narrative that resonates all too well in Malaysia, Ignatius explained.

And having spent months building up an extensive network of political and religious connections across the country, his reputation is now such that he is virtually untouchable, opined Ignatius.

Related articles: