Catching COVID may cause changes to the brain, a study suggests.

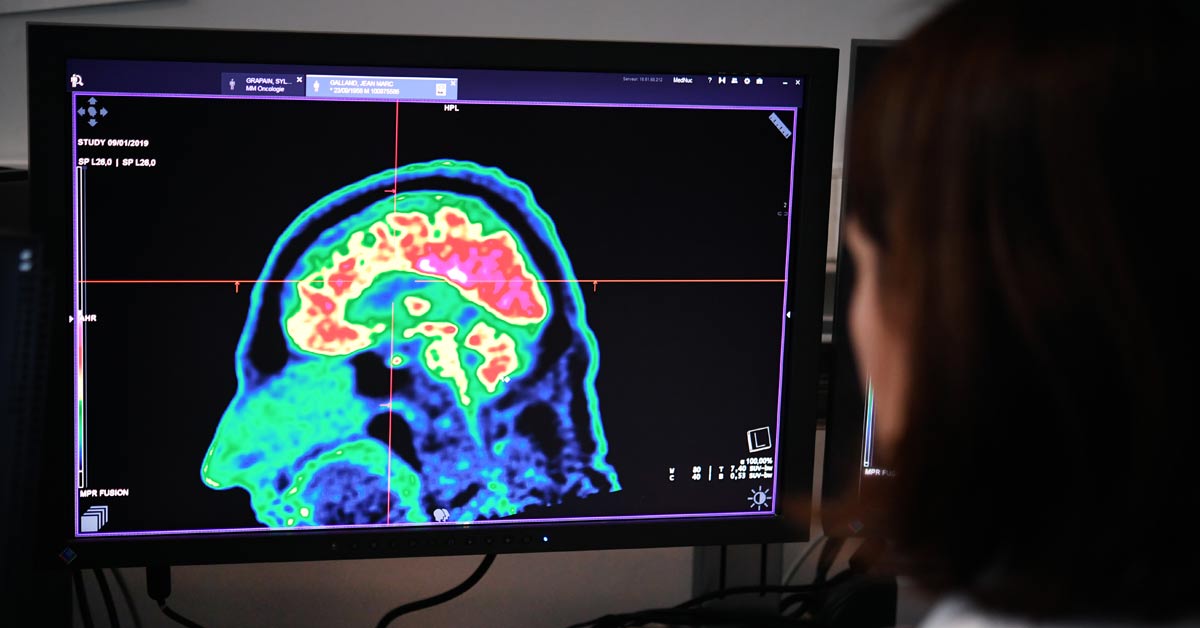

Scientists have found significant differences in MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) scans before and after infection.

Even after a mild infection, the overall size of the brain had shrunk slightly, with less grey matter in the parts related to smell and memory.

The researchers do not know whether the changes are permanent but stressed the brain could heal.

The new study is published in the journal Nature.

Lead author Prof Gwenaelle Douaud, from the Wellcome Centre for Integrative Neuroimaging, at the University of Oxford, said: "We were looking at essentially mild infection, so to see that we could really see some differences in their brain and how much their brain had changed compared with those who had not been infected was quite a surprise."

The United Kingdom (UK) Biobank project has followed the health of 500,000 people for about 15 years and has a database of scans recorded before the pandemic, so it provided a unique opportunity to study the long-term health impacts of the virus.

The scientists rescanned 401 participants 4.5 months, on average, after their infection, 96 percent of whom had had mild COVID. 384 participants had not had COVID.

They found the overall brain size in infected participants had shrunk between 0.2 and two percent.

There were losses in grey matter in the olfactory areas, linked to smell, and regions linked to memory.

Those who had recently recovered from COVID found it a bit harder to perform complex mental tasks.

But the researchers do not know whether the changes are reversible or truly matter for health and wellbeing.

"We need to bear in mind that the brain is really plastic – by that we mean it can heal itself – so there is a really good chance that, over time, the harmful effects of infection will ease," Prof Douaud said.

The most significant loss of grey matter was in the olfactory areas – but it is unclear whether the virus directly attacks this region or cells simply die off through lack of use after people with COVID lose their sense of smell.

It is also unclear whether all variants of the virus cause this damage.

The scans were performed when the original virus and alpha variant were prevalent and loss of smell and taste were a primary symptom.

But the number of people infected with the more recent Omicron variant reporting this symptom has fallen dramatically.

'Your Mind Is What Is Being Exercised'

Paula Totaro lost her sense of smell when she caught COVID, in March 2020.

"When it was gone, it was like living in a bubble or a vacuum – I found it really isolating," she said.

But after contacting the charity AbScent, which supports people who have lost their ability to smell and taste, she began smell training.

"What smell training does – particularly if you do it twice a day, regularly, religiously – is it forces you to take the smell, allow it to go back into your nose and then to think about what it is that you're smelling," she said.

"And that connection between what's in the external world and what goes into your brain and your mind is what is being exercised."

Ms Totaro has now recovered most of her sense of smell – although she still has trouble identifying what different smells are.

"It's a mix of joy that the sense has come back but still a little bit of anxiety that I'm not quite there yet," she said.

UK Biobank chief scientist Prof Naomi Allen said: "It opens up all sorts of questions that other researchers can follow up about the effect of coronavirus infection on cognitive function, on brain fog and on other areas of the brain – and to really focus research on how best to mitigate that."

Prof David Werring, from the University College London Institute of Neurology, said other health-related behaviour could have contributed to the changes seen.

"The changes in cognitive function were also subtle and of unclear relevance to day-to-day function," he said.

"And these changes are not necessarily seen in every infected individual and may not be relevant for more recent strains."