A recent Oxford University study revealed changes in several parts of the brain after people contracted the virus, including those who experienced mild symptoms. We have known for some time now that COVID-19 can affect the nervous system.

Some people who contracted the SARS-CoV-2 virus have suffered from a number of neurological complications including confusion, strokes, impaired concentration, headaches, sensory disturbances, depression, and even psychosis, months after the initial infection.

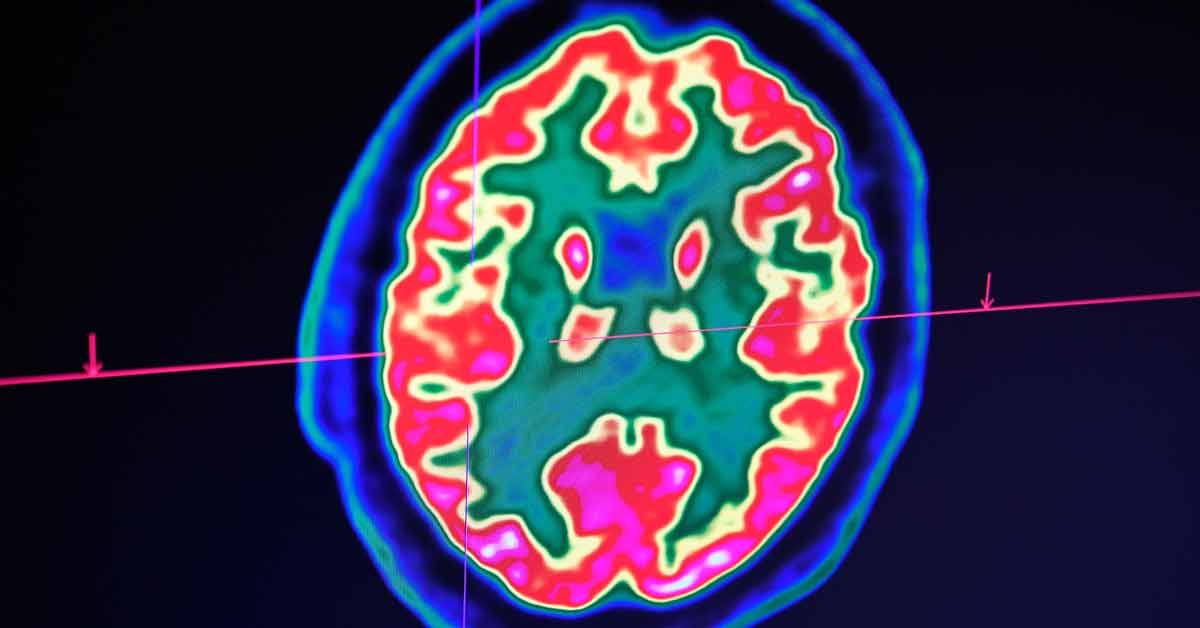

Now, researchers at the University of Oxford have conducted the first major peer-reviewed study comparing the brain scans of 785 people, aged 51 to 81 of whom 401 had contracted COVID and 384 had not. There were, on average, 141 days between testing positive for COVID and the second brain scan.

The study revealed that, when compared to the scans of a control group, those who tested positive for COVID had greater overall brain shrinkage and more grey matter shrinkage and tissue damage in regions linked to smell and mental capacities months after the initial infection.

Although the research does shed some light on the ongoing symptoms of long COVID, we would caution against generalising the findings to the population at large before more research is conducted.

Researchers said even though the effects were more pronounced in older people who had been hospitalised for their symptoms, even those with mild symptoms had some changes.

“Despite the infection being mild for 96 percent of our participants, we saw a greater loss of grey matter volume, and greater tissue damage in the infected participants, on average 4.5 months after infection,” said Professor Gwenaëlle Douaud, lead author on the study.

“They also showed greater decline in their mental abilities to perform complex tasks, and this mental worsening was partly related to these brain abnormalities.”

The study was conducted when the Alpha variant was dominant in Britain and is unlikely to include anyone infected with the Delta variant. The researchers also did not say if vaccination against COVID had any impact on the condition.

The scans they did reveal changes in several parts of the brain after people contracted COVID, including:

1) Greater reduction in grey matter thickness and tissue contrast in the orbitofrontal cortex and parahippocampal gyrus. The orbitofrontal cortex is the part of the brain that controls reward, emotion and fluctuations in mood and feelings of sadness. It is also involved in cognitive function and decision-making. The parahippocampal gyrus plays a role in the control of our emotions as well as an important role in memory retrieval and spatial awareness and processing. We have seen symptoms of depression, anxiety and “brain fog” where people are prone to memory issues after a COVID infection.

2) Greater changes in markers of tissue damage in regions functionally connected to the primary olfactory cortex. This is the part of the brain for processing and perception of smell; it also helps link smells to certain memories and survival responses. Loss of sense of smell has been a hallmark symptom of COVID and this may explain why that is.

3) Greater reduction in global brain size, essentially meaning the participants’ brains were smaller after testing positive for COVID than when scanned before the infection.

It is not uncommon for our brains to shrink as we get older, the natural ageing process results in the loss of grey matter every year, on average between 0.2 percent and 0.3 percent, according to researchers. But the study found that, compared with uninfected participants, those who contracted COVID – even those who had mild cases – lost between 0.2 percent and 2 percent between scans.

The study also found that participants who had suffered from COVID exhibited a greater decline in efficiency and attention when performing a complex cognitive task.

The Oxford study is the first study to make such a direct link between COVID infections and changes in the brain. It goes some way to providing us with the beginnings of an explanation about the myriad neurological symptoms people with long-COVID complain about, although researchers stress that more studies are needed.

We do not know whether the changes in the brain demonstrated in this study are long-term or permanent, or whether they would be the same for younger people, who generally (but not always) get milder COVID symptoms.

Since the study was conducted during the reign of the Alpha variant, more work needs to be done on those who contracted the Delta and Omicron variants to see if similar changes are found.

The timing of the study also means that the participants were unlikely to have been vaccinated. Now, with so many people vaccinated, it would be useful to know if the vaccines offer a layer of protection.