When the military junta in Thailand, also known as the National Council for Peace and Order (NCPO), seized power on 22 May, 2014, one of the main reasons it gave for doing so was to address the high levels of corruption plaguing the country under then-Prime Minister Yingluck Shinawatra. Now, with an election hopefully on the horizon, the question on every Thai’s mind is whether the junta been able to rid or reduce corruption in the country.

Going by a recent poll by Bangkok’s Suan Dusit Rajabhat University, more than half of Thais don’t seem to think so. The poll, conducted in March this year, asked respondents whether they believed the military government could solve the problem of corruption in Thailand. 56.6 percent of the respondents said “no”, 23.4 percent said they were uncertain, and only 19.9 percent said they thought the government could use its extraordinary power to rid the country of corruption.

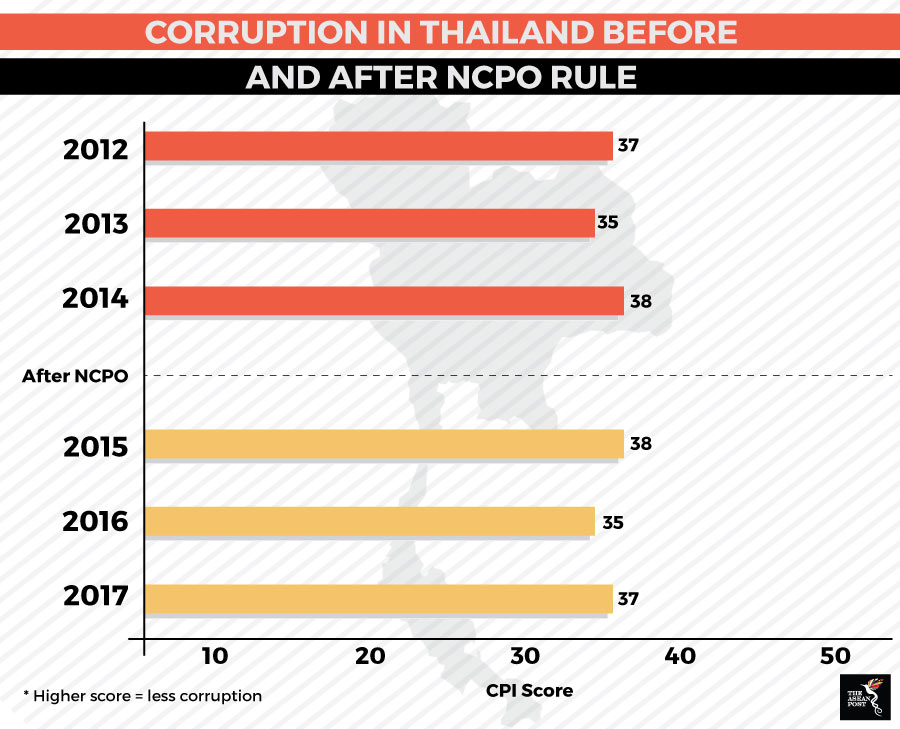

Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index (CPI) also seems to indicate that the military junta’s rule did not yield much in terms of eradicating corruption. According to the index - where the higher the score, the lower the level of corruption - prior to the military coup, Thailand scored 37 out of 100 in 2012, 35 out of 100 in 2013, and 38 out of 100 in 2014. Under military rule, Thailand scored 38 out of 100 in 2015, 35 out of 100 in 2016, and 37 out of 100 in 2017.

Source: Transparency International

Source: Transparency International

Sungsidh Piriyarangsan, an associate professor and Dean of the College of Social Innovation at Rangsit University, revealed that corruption in the government will cost the country up to Thai baht 100 billion (US$3 billion) this fiscal year. To top it off, Sungsidh said his “cautious estimate” puts the amount at between Thai baht 50 billion (US$1.5 billion) and Thai baht 100 billion (US$3 billion) for 2018 alone. He based his estimates on the findings of 14 studies on corruption funded by the Public Sector Anti-Corruption Commission (PACC).

In fact, according to the World Bank, if developing countries can control corruption and enforce the rule of law, per capita income could possibly increase fourfold over the long term. It estimates that on average, the business sector could grow three percent faster. Corruption is seen as a de facto tax on foreign direct investments (FDIs), amounting to around 20 percent of the total investment amount.

The cost of corruption is especially pertinent considering data revealed by the United Nations (UN) and the Asian Development Bank (ADB) regarding poverty in Asia last year. According to both organisations, some 400 million people, a tenth of Asia Pacific's population, live on less than US$1.90 a day - the global definition of extreme poverty - despite the region's impressive economic growth.

Keeping the NCPO in control

A big weakness in Thailand’s political system is that there are no agencies which can truly scrutinise politicians. While parliament and independent agencies do exist, they are unable to take politicians to task and make them accountable for their actions. This muddies the situation in Thailand given the NCPO’s newly unveiled 20-year National Strategy.

There are six strategic areas under the 20-year National Strategy encompassing security, competitiveness enhancement, human resource development, social equality, green growth and rebalancing and public sector development.

For security in particular, the key focus is national security, keeping people happy, managing situations to ensure security, safety and order at all levels, as well as preventing and solving existing and future security issues. This leaves a lot of space to control politicians’ movements. The fact that those in the military also make up a significant portion of those in charge of ensuring politicians abide by the 20-year National Strategy – The National Strategy Committee – just serves to heighten the concern that the National Strategy is merely a document to keep the military junta in control.

While corruption is still rife in Thailand and may become worse in the future, it also provides the military junta with the excuse it needs to keep politicians in check under its 20-year National Strategy. While this isn’t necessarily a bad thing, it does leave a lot of room for abuse if the National Strategy Committee so chooses.

Statistics have shown that the NCPO has not done much in terms of addressing corruption, and providing it another 20 years to work on this is possibly not the best method of dealing with the problem. One of the most crucial steps in lowering corruption to a lesser degree would be to ensure that the judiciary in the country is completely independent of the administration. Currently, the head of the judiciary – the minister of justice – sits in the Prime Minister’s Office. Perhaps this could be a good place to start.

Articles selected as Top Stories of 2018 are those that were the most popular among readers of The ASEAN Post for the month in question.

Related articles: