The last few times her superior at a school in Mataram, on the Indonesian island of Lombok, called her on the telephone, the conversation turned uncomfortable after it veered to include the vulgar detail of his sexual exploits and an invitation to sexual encounters in hotels. While she wanted to report him for sexual harassment, the fear of being fired stopped her as she didn’t have proof.

The next time his unwelcomed call came, she was ready and recorded their conversation. True to fashion, the conversation between the headmaster, H Muslim, and the teacher, Baiq Nuril Maknun, turned indecent again. Her colleague, Imam Mudawin, heard about the incident and used the audio file to lodge an official complaint against the headmaster to the Mataram Education Agency.

In an unthinkable twist, the Indonesian Supreme Court in Jakarta overturned a 2017 acquittal from a lower court and convicted Baiq Nuril of recording and spreading indecent material under the country’s electronic information and transactions law. In September, Baiq Nuril was sentenced to six months in jail and fined IDR500 million (US$34,000).

The case has sparked criticism among activists and the public who argue that Baiq Nuril was the actual victim of sexual harassment from Muslim. Executive Director of Amnesty Indonesia, Usman Hamid, said instead of looking at the abuse carried out by Muslim against Baiq Nuril, the system focussed on criminalising her actions to redress the abuse.

“It appears a woman was criminalised simply for taking steps to redress the abuse she experienced.

“Unsolicited, sexually explicit and abusive telephone calls would constitute sexual harassment and should be investigated as a priority, with charges brought accordingly. It is a travesty that while the victim of the alleged abuse has been convicted, little if any action appears to have been taken by the authorities to investigate what appear to be credible claims,” said Usman as quoted by the Guardian.

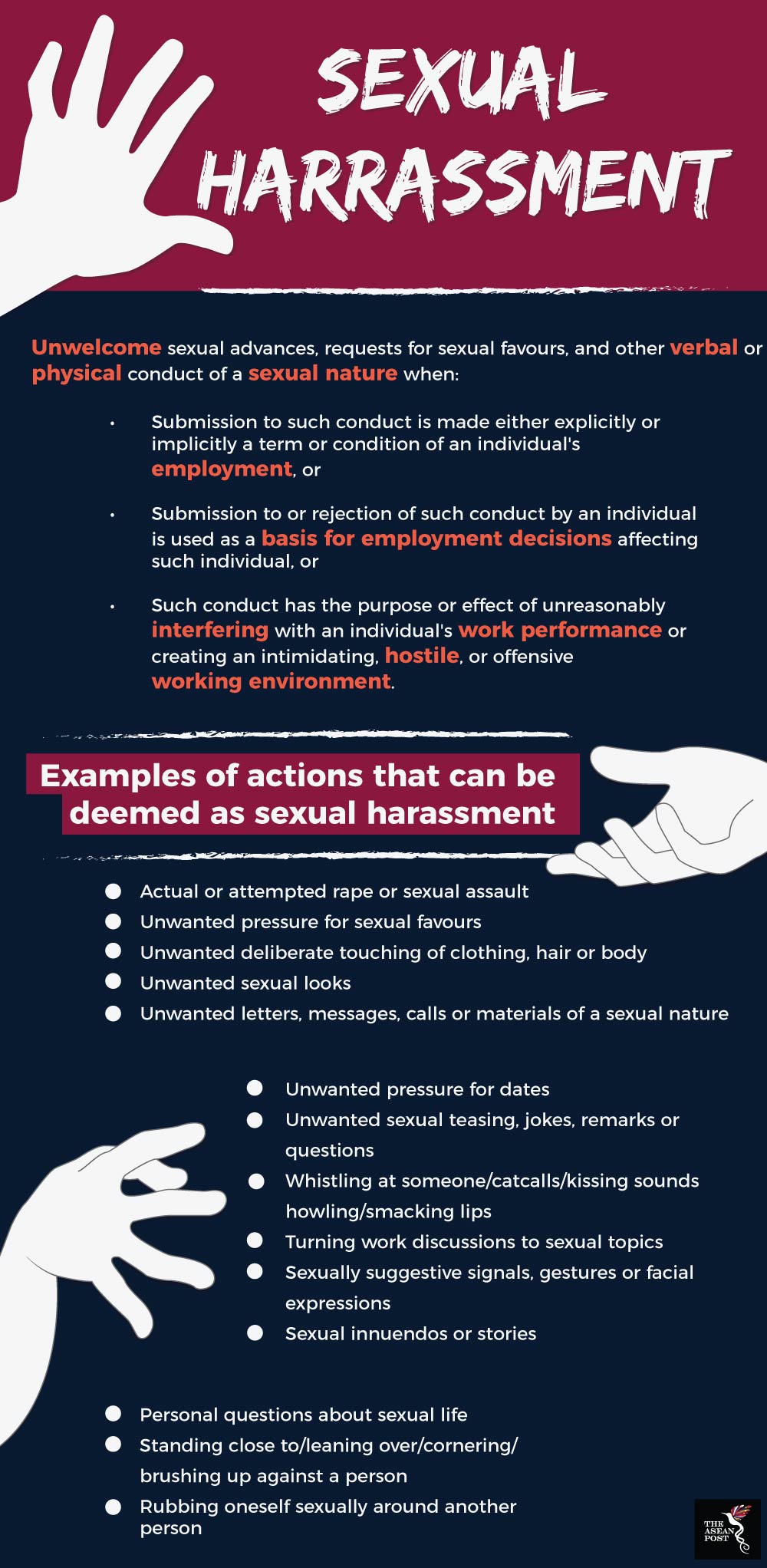

Sexual harassment is any unwelcome verbal or physical conduct or behaviour of a sexual nature that might reasonably be perceived to cause offence or humiliation to another. At the workplace, these behaviours include actions that interfere with work, is made a condition of employment, or creates an intimidating, hostile or offensive work environment. Sexual harassment may occur between persons of the opposite or same sex, and both male and female can be the perpetrators and the victims.

Source: Various sources

Source: Various sources

On the rise

In Indonesia, incidences of sexual harassment continue to rise. Data from the Indonesian National Commission on Violence against Women (Komnas Perempuan) shows that of the 259,150 cases of violence against women in 2016, some 3,495 are domestic sexual harassment and 2,290 were sexual abuse at the community or workplace.

However, the number may be just the tip of the iceberg as many cases go unreported. Director of Legal Aid Institute for Indonesian Women Association for Justice (LBH APIK) Jakarta, Veni Oktarini Siregar, said that of the dozens of sexual abuse cases against women received by his agency, only a few were taken to court as most women refuse to file as they are disappointed or traumatised by the system. She said that women who are victims of such cases are often shamed and victim-blamed.

“No one believes that somebody has committed a sexual assault in a public space,” Veni said.

This is worrying in a country where, according to a government survey released in 2017, one third of its women have faced physical or sexual violence. However, the Indonesian government’s attitude has also been more ‘relaxed’ in accepting violence of a sexual nature as the norm.

In the world’s most populous Muslim country, women applying to join the security forces were checked not only for their health, but also for whether they have had any prior sexual experience. The virginity test, a practice that has been going on for more than five decades, was highlighted in 2014 by a Human Rights Watch report.

Cases as this are one of the many reasons why women do not want to come forward in the event of abuses. Rulings that victimise the victims also deter other victims from coming forward and reporting abuses, leading to sexual harassment being sorely underreported. For Baiq Nuril, the unfair and unreasonable conviction must feel like a second violation.

Related articles:

Ending the violence against women in the region

Women’s rights in the region still has a long way to go