The issue of human rights has largely flown under the radar for the 81 parties contesting the Thai general election this Sunday.

Freedom of expression, peaceful assembly and press freedom has deteriorated in Thailand since the military junta led by Prayut Chan-o-cha took over in 2014 and started the longest period of army rule in modern Thai history. Several hundred activists and dissidents have since been called national security threats and have faced serious criminal charges such as sedition, computer-related crimes and lese majeste (insulting the monarchy) for peaceful expression of their views.

According to the 2018 Human Rights Watch report titled ‘Thailand: Lift Draconian Speech Restrictions’, since the beginning of last year, more than 100 pro-democracy activists have been prosecuted for peacefully demanding that the junta hold elections as promised.

The Prayut-led National Council for Peace and Order (NCPO) has created a military-drafted constitution and set up an administrative structure which blocks any real implementation of human rights policies. Chances are that even if a new government is formed after 24 March, human rights are unlikely to improve.

Economy first, human rights later

Many of the junta’s most vocal critics have already fled overseas, fearing for their lives. Combined with issues such as social and economic inequality being of more importance to voters, it is understandable why human rights have not featured in mainstream political debates. While the economy has picked up after the coup, poverty and inequality continue to pose significant challenges because of slowing economic growth, decreasing prices of agricultural products and ongoing droughts.

“The debate is mostly on ‘mouth and stomach’ issues (bread and butter) such as the high cost of living, low income, low crop price, low wages and salary, growing household indebtedness, landlessness, unemployment, etc.,” said Dr Termsak Chalermpalanupap, a lead researcher at the ASEAN Studies Centre.

“These are real life-and-death issues affecting the immediate livelihood and well-being of a large majority of Thai voters. Human rights are abstract; human rights protection and promotion can wait for the time being,” added Dr Termsak, who is also a member of the Thailand Studies Programme at the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute in Singapore.

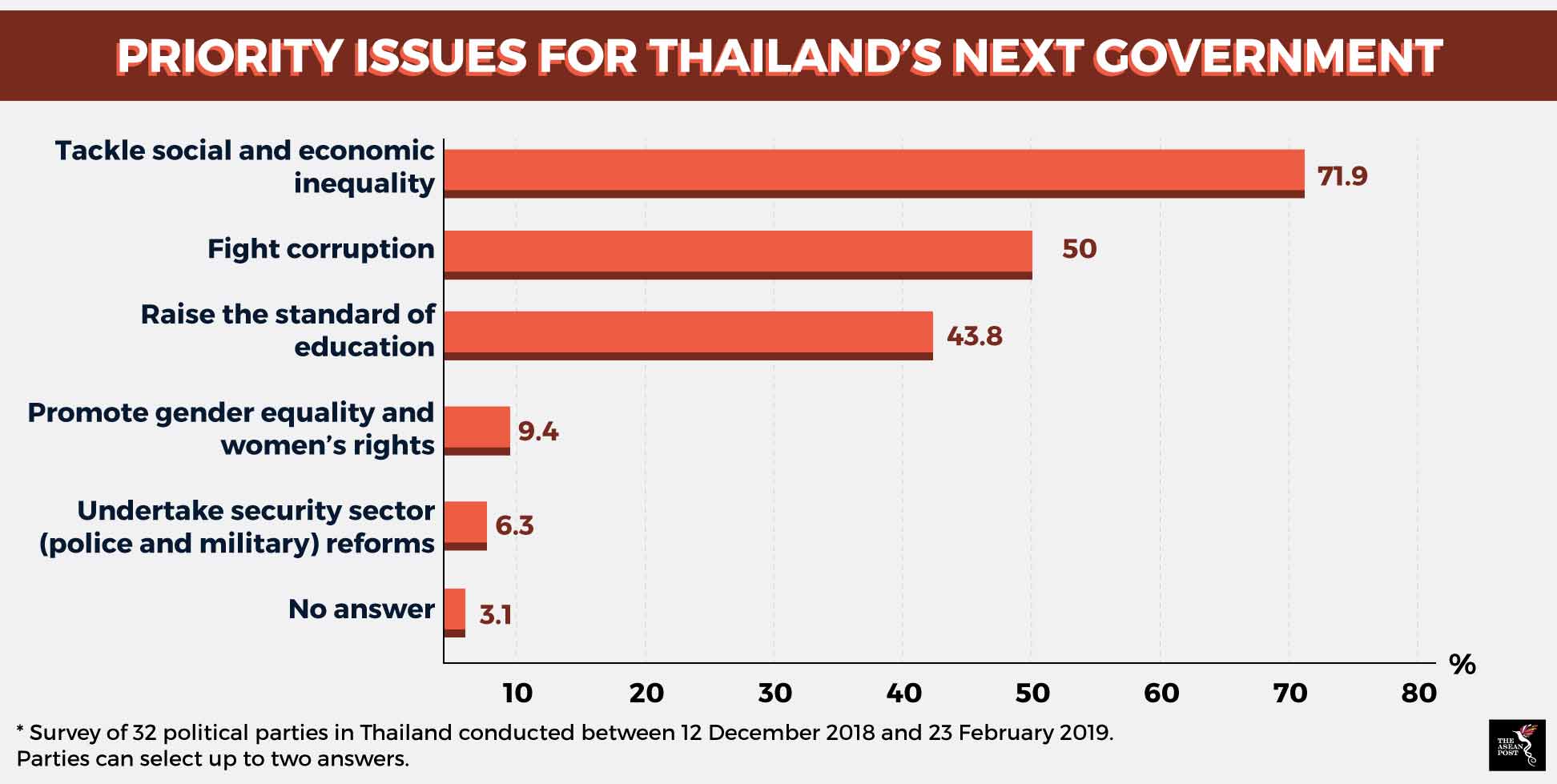

A survey of 32 Thai political parties conducted by the International Federation for Human Rights earlier this month found that human rights was not a critical issue for them and that there is limited support for measures aimed at improving freedom of opinion and expression.

A report on the survey titled ‘More shadows than lights – Thailand’s political parties and their human rights commitments’ released on 14 March revealed that despite some positive commitments regarding human rights defenders, detention conditions, and refugees and asylum seekers, political parties were reluctant to address some of the more critical issues impacting human rights and democratic principles in Thailand. Only a small minority favoured the amendment of criminal defamation laws while the overwhelming majority did not support the removal of jail terms for violators of Article 112 of the Criminal Code (lese majeste).

Politicians charged

In the build-up to the election, only Thailand’s rising political star, Thanathorn Juangroongruangkit, the head of the Future Forward Party, has raised human rights as an issue – saying in interviews that Thailand’s awareness of human rights is still very low and that ASEAN has to address it together.

Thanathorn, a charismatic young leader who has spoken out in support of free speech, is no stranger to human rights abuse after being charged under the Computer Crime Act in August for criticising the military government in a Facebook video. Prosecutors will meet on Tuesday, two days after the election, to decide whether to indict him. He could face up to five years in prison.

Pichai Naripthaphan, Watana Muangsook and other key members of the Pheu Thai Party have also been charged with sedition and computer crimes while Police General Seripisut Temiyawet, leader of the Seri Ruam Thai Party, has also seen computer crime complaints filed against him.

However, it would be unfair to single out the Thai government for its poor human rights record.

ASEAN has human rights issues which affect each of their 10 members, and the practice of using sedition charges and cyber-security laws to suppress opposing views is common across the region.

Other issues such as the lack of press freedom, religious freedom, LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender) rights, privacy shortcomings and extrajudicial killings are just as rampant.

While some politicians have verbally supported the development of legislature to address these issues, they have failed to create any meaningful policy initiatives that can be implemented on the ground to safeguard the rights of vulnerable groups.

With elections in Indonesia next month and mid-term elections in the Philippines in May, human rights supporters will be keeping a close eye on the political discourse in these two countries as well.

Related articles:

Thai junta pegs economic fortunes to China