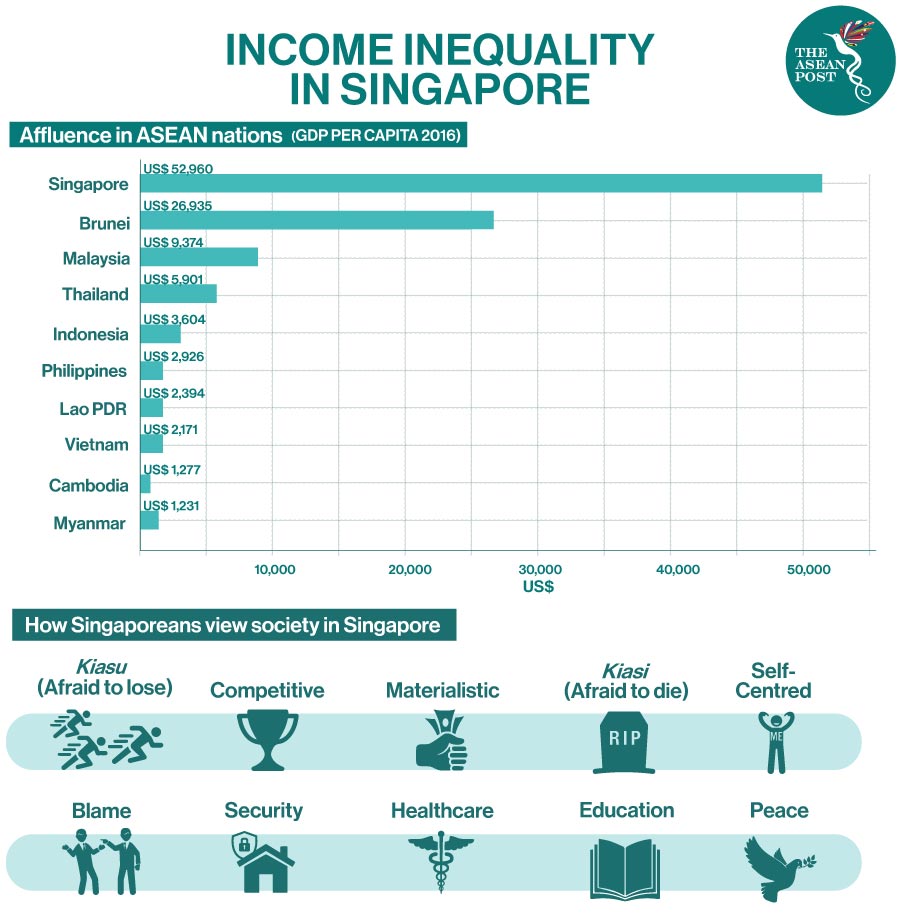

Singapore as a nation is often seen as being materialistic when compared to its regional peers, with a 2012 study by the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy’s Institute of Policy Studies (IPS) finding that even Singaporeans view their society as kiasu (afraid to lose), competitive and materialistic.

Regardless of whether this reputation is deserved, it points towards larger socioeconomic trends in the island republic which are driving the current social fabric at its most fundamental level. First among these is an overwhelming individual desire to succeed in the face of disparities in income and economic opportunity.

While these factors are present to some extent in any developed nation, population pressure coupled with a dearth of physical resources has amplified their effects in Singapore, placing the pursuit of the “Singaporean Five Cs” – cash, credit card, car, condominium and country club membership – farther and farther out of reach of the average Singaporean.

First world problems

“The pressure to keep up is immense. You need to show that you’ve made it: Armani, Gucci, Prada, whatever it takes, you have to buy it and put it somewhere people can see. Even though my family is well off, I still found it overwhelming,” says an investment banker who recently relocated from the island republic to Malaysia.

Singaporeans from less affluent backgrounds feel this pressure even more acutely, particularly as 73 percent of Singapore’s wealth is owned by the top 20 percent of income-earning households, according to global wealth estimates by Credit Suisse.

“In the long run, early year income poverty has a long-term negative impact on an individual's brain development, as well as development in cognitive skills and social behaviours. It is of utmost importance to support children in low-income families. Adjusting wages for very low wage jobs is often necessary,” says Wei-Jun Jean Yeung, Provost's Chair Professor of the Department of Sociology at the Singapore-based Asia Research Institute.

“Providing more tax incentives for high income groups to contribute back to society, having a sliding tax rate scheme according to household income, and higher tax for luxurious goods have also been used in other countries.”

Income inequality is generally expected to rise in developing economies. This effect is particularly visible in cities, with business intelligence firm Euromonitor International establishing a positive correlation between the Gini coefficient, a standard economic measure of income disparity, and the size of an urban population.

As a city-state, Singapore is particularly vulnerable to these pressures, with a population of 5.61 million in 2016 concentrated in a single island-wide urban conglomeration. In addition, it is by far the most affluent nation among ASEAN member states, with a gross domestic product (GDP) per capita of US$52,960 in 2016, according to market research firm Statista.

This figure is nearly twice that of ASEAN’s second most affluent nation, Brunei (US$26,935 per capita), and more than five times that of the third, Malaysia (US$9,374 per capita). With greater wealth concentrated in fewer hands within the third second smallest population in ASEAN, it’s no surprise that Singapore had one of the highest Gini coefficients in the region in 2017 at 0.459. The coefficient ranges from 0 to 1, representing perfect income equality and inequality respectively.

Corrective measures

It’s worth noting that income disparity and economic success have been themes in the city-state’s development since 1965. Despite a bleak economic outlook at the time of its independence, Singapore transformed itself from a regional trading port in the 1960s to a low value-added labour-intensive manufacturing base in the 1970s, eventually ending up today as a global hub for professional business and financial services.

However, pressures from income disparities in the republic will only increase with time, as Singapore’s population – which is projected to reach 5.86 million by 2022 – outgrows the 719.9 square kilometres of land available to it. Without concerted, proactive intervention at the policy level, income inequality and disparities in economic opportunity may distort the island nation’s social fabric beyond its current kiasu penchant for competition and materialism.

“One young man left a comment on my Facebook page. His name is Chee Kian. He is a teacher. His father was a taxi driver, his mother a cleaner,” said Singapore's Education Minister Ong Ye Kung in a Parliament address earlier this month.

“He said: ‘…I worked hard through the education system to achieve what I am today. However, I notice that it is getting harder for poorer students to break through the system like [in] the past as privileged kids garner [many] advantages since young. [We need to] bridge the gap between the rich and the underprivileged.’"

Previous initiatives by the Singaporean government aimed at bridging the income gap have linked wages to productivity growth, in line with principles introduced by the 2010 Economic Strategies Committee.

However, in his 2012 report Singapore's Rising Income Inequality and a Strategy to Address It, IPS Economics and Business research fellow Dr Tan Meng Wah argues that incremental wage adjustments in non-tradeable services sectors, coupled with other measures such as reducing the nation’s dependence on foreign workers, can reduce income disparities while keeping Singapore competitive in terms of regional labour rates.

“From the perspective of maintaining economic competitiveness, talents and the ability to innovate is crucial. This can be achieved both from building talents inside of Singapore and from a steady flow of immigrants. So, the Singaporean government's recent focus on increased early childhood investment, a calibrated volume of immigration, and the stress on social integration are all very good policies to reduce income inequality and maintaining competitiveness at the same time,” explained Yeung.

Whether government intervention is more effective in the form of productivity-linked or incremental wage growth remains to be seen. However, in bridging the income gap, the Singaporean government must keep in mind that not all inequality is detrimental, with a healthy level of disparity necessary to provide incentives and to foster competition.

This article was first published on 1 July, 2018.