The euphoria surrounding possible reconciliation in the Korean Peninsula has now been dampened after North Korea threatened to pull out from talks with the United States (US) earlier today. This came after Pyongyang backed out of a high-level meeting with Seoul and threatened to do the same with Washington.

US President Donald Trump was scheduled to meet head of the North Korean dictatorial regime, Kim Jong-un in Singapore on 12 June. Their discussions were slated to centre on denuclearisation and the economic interests of the hermit state, which has suffered immensely from United Nations (UN) backed sanctions of late.

In a statement carried by North Korean state media mouthpiece, Korean Central News Agency (KCNA), First Vice Foreign Minister Kim Kye Gwan said that Pyongyang may have to reconsider participation in the talks if the Trump administration continues to push for North Korea to unilaterally give up its nuclear arsenal.

“If the US is trying to drive us into a corner to force our unilateral nuclear abandonment, we will no longer be interested in such dialogue,” the minister was quoted as saying by Agence France Presse (AFP).

The move comes after North Korea protested the Max Thunder military practice between South Korea and the US, which it claims to be a “rude and wicked provocation.” Pyongyang seemed to have interpreted the drills as preparatory steps taken for a possible invasion.

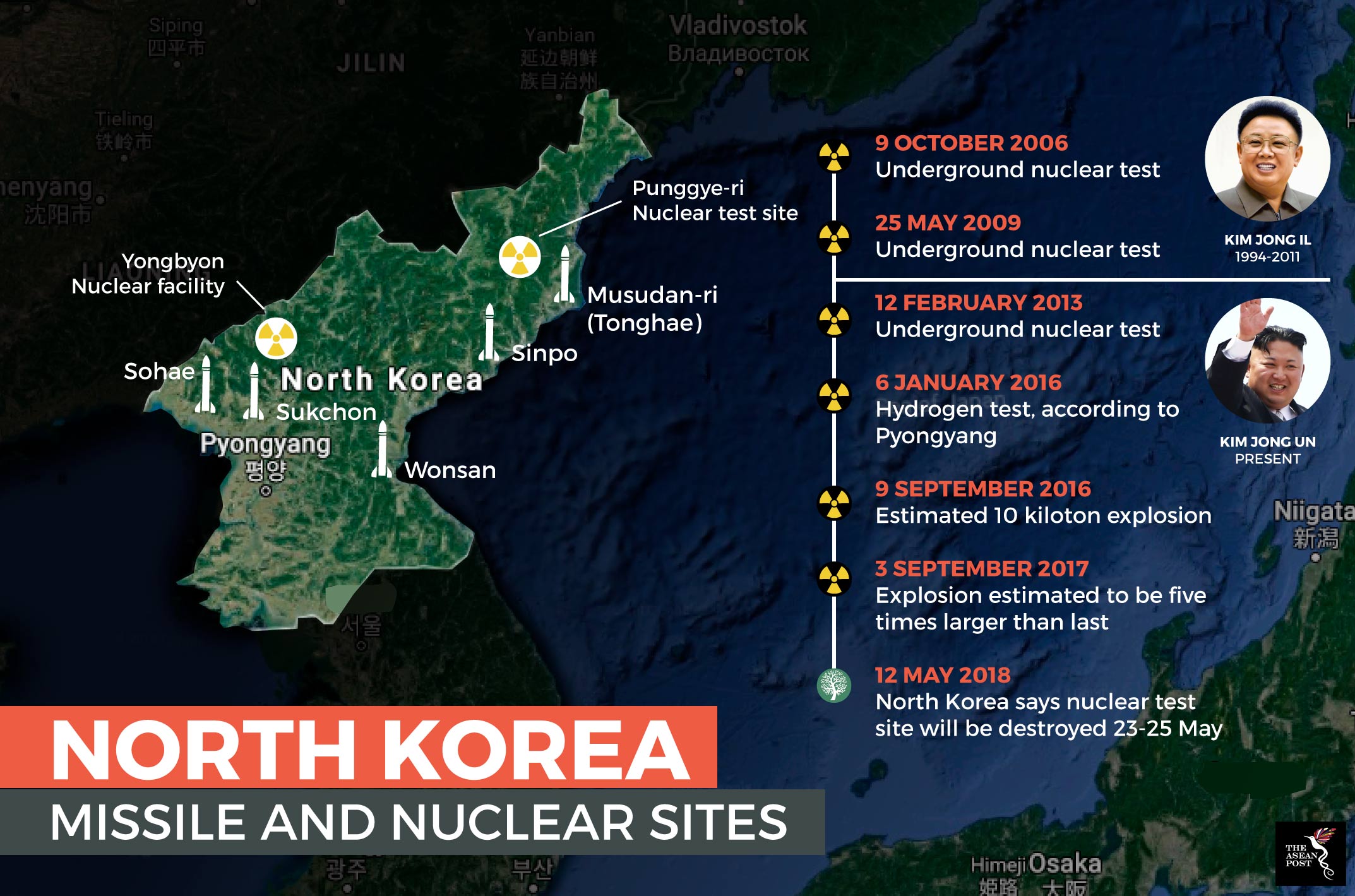

Kim’s regime has continued conducting nuclear and long-range intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) tests up to the end of last year. However, his aggressive stance mellowed considerably following his agreement to send a North Korean contingent to the Winter Olympic Games which took place in South Korea at the start of the year.

Soon after, high-level talks were conducted between officials of both North and South Korea, culminating in a historic meeting of the leaders of the two nations at the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) which physically separates them. Nevertheless, the rapprochement was just a precursor to what was supposed to come next – an epoch-making meeting between the leaders of the US and North Korea, which would have been the first in the history of the Korean conflict.

Source: AFP

Defining denuclearisation

The possibility of a North Korean pull-out is not far-fetched. In fact, analysts and observers have warned of a definitional issue which may upend progress towards peace in the Korean Peninsula. Both Pyongyang and Washington are coming into these talks with different ideas of what “denuclearisation” means.

To the US, it means North Korea should halt its nuclear operations and hand over its existing nuclear systems and missiles, while permitting access to international inspectors to verify the state is abiding by its promises. However, Kim’s regime sees denuclearisation as a principle which should also be applied to the US. This would mean the removal of the nuclear umbrella placed over South Korea and Japan, as well as the withdrawal of US troops stationed in Seoul.

North Korea’s other concern is the avoidance of the fate which befell former Libyan leader Muamar Gaddafi following his agreement to dismantle his country’s weapons of mass destruction (WMD) programme. Although there are competing narratives as to why Gaddafi fell from his leadership perch, to Kim, it is because the terms of Libyan nuclear disarmament gave the US and its allies an upper hand to use as “an invasion tactic to disarm the country.”

Hence, when US national security adviser John Bolton alluded to North Korea following a similar disarmament model to Gaddafi’s, officials in Pyongyang may have realised that the US intends for Pyongyang to give up its nuclear capabilities without Washington agreeing to lift its nuclear guarantee to Japan and South Korea.

This time however, Washington is faced with a negotiator which has a superior nuclear arsenal compared to Libya under Gaddafi, and hence a larger bargaining chip to contend with. Pyongyang has even gone as far as to refuse economic support from the US as it perceives that Washington has been painting an image of a weak North Korea crumbling under pressure from sanctions and is in desperate need of economic help.

So far, Washington has stated that it is continuing with plans to have the summit in Singapore later in June. Whether Pyongyang will throw a spanner into these works is anyone’s guess, but until both sides can agree upon a common definition of “denuclearisation,” peace in the Korean Peninsula may remain a pipe dream.