Hunted by poachers for their skulls and tails, and almost every other body part in between, tigers are amongst the most threatened wildlife on earth. Killed for use in traditional medicine, folk remedies, as jewellery parts, and for their pelts mostly as luxury decor, only six out of the original nine sub-species of tigers have survived till today. Compared to the 100,000 tigers estimated to have roamed the earth during the 1900s, there are now only around 3,890 tigers left in the wilderness.

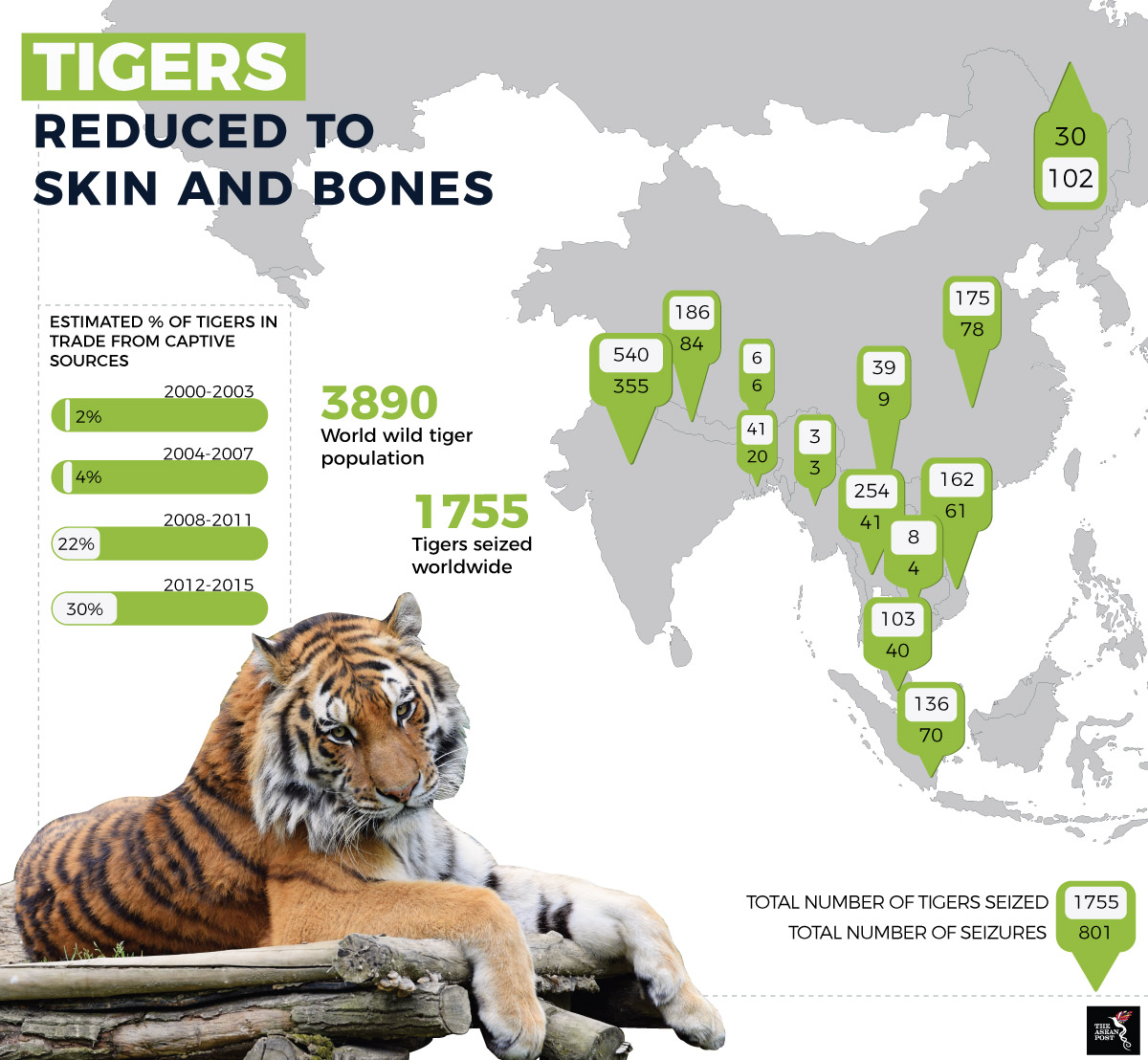

Between January 2000 and December 2015, it has been estimated that a minimum of 1,755 and maximum of 2,011 tigers were killed based on the analysis of seized tigers, alive and dead, as well as tiger parts over the 16-year period. This estimation, provided in a report by TRAFFIC, a wildlife trade monitoring network, is based on 801 reported seizures across 13 Tiger Range Countries (TRCs). ASEAN countries account for more than half of the TRCs. The TRCs in the region are Indonesia, Lao PDR, Myanmar, Thailand, Vietnam, Cambodia and Malaysia. The other TRCs are Bangladesh, Bhutan, China, India, Nepal and Russia.

According to the report, during this period of time, on average, a minimum of 110 tigers were seized annually and 50 seizures were reported annually. The highest number of seizures were reported from 2008 to 2011 and the highest number of seizures was reported by India, accounting for 44 percent of all reported seizures. In 2016, the Cambodian tiger was declared “functionally extinct” with no breeding populations left in the wild.

Source: TRAFFIC

The approximate number of tigers killed is based on a minimum estimate as most poachers and traders when caught are in possession of butchered tiger parts such as claws, canine teeth, heads, ribs, legs, penises, skulls and jaw bones. If, for example, between one and 18 claws are found in a seizure, it is estimated that one single tiger was killed as a tiger has 18 claws. Likewise, if the seizure recorded four claws, one head, and two ribs, it is also deemed to equate to a single tiger because the parts involved amount to no more than those that can be harvested from one animal.

Human greed

The biggest factor driving the tiger population to the brink of extinction is the value of these majestic mammals as ingredients in traditional Chinese medicines and remedies. For enthusiasts, tiger parts are believed not only to be the cure for almost every ailment under the sun, but also have the ability to replenish the body’s essential energy. Even though no evidence-based studies have proven this belief, many still cling to the idea that eating tiger parts can transfer the animal’s mystical vigour to the person who consumes them. With the international ban on tiger trading under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES), on the black market, a tiger is literally worth its weight in gold.

Aside from poachers and animal traffickers, tigers are also under constant threat from habitat loss. Tigers have lost about 93 percent of their historical range. Deforestation for timber and agriculture, as well as forest opening for roads and other human activities, impact the survivability of tigers. Through these activities, tiger habitats are degraded, fragmented or destroyed. This is key as tigers need large connected territories to thrive. In fragmented areas of similar size, fewer tigers can survive. Fragmentation of territories leads to a higher risk of inbreeding and exposes the tiger population to poaching as they venture out beyond protected areas. When India started prioritising core habitats maintenance for breeding, habitat connectivity and protection from poaching, its tiger population was found to have increased by 30 percent to an estimated 2,218 tigers in 2016 compared to an estimated 1,706 individual tigers in 2010.

Poachers getting desperate

TRAFFIC Southeast Asia’s Acting Regional Director, Kanitha Krishnasamy, said that as the number of tigers dwindle further, the syndicates of poachers and traffickers that target the animal are only going to get bolder and more determined. Those sourcing the tigers, said Kanitha, are persistent and their numbers are only likely to grow. This includes illegal hunters that come armed with high-powered modified firearms, bullets and explosives, as well as an army of poachers laying out a blanket of snares.

“Every time a poaching or trafficking gang is defeated, it is a win for enforcers at the forefront of the battle against wildlife trafficking, and for the rule of law. No one should be allowed to get away with or profit from the theft of endangered species,” she said in the press statement on Global Tiger Day that falls on 29 July every year.

By nature of it supply and demand, the tiger trade is international in nature, with much of it happening between Africa and Asia, as well as intraregional in Asia. For example, wildlife trade in Lao PDR’s Special Economic Zone (SEZ) in Bokeo Province caters predominantly to Chinese and Vietnamese clients, while Vietnamese and Chinese endangered wildlife poachers and traders have been caught operating in the jungles of Malaysia. There are also prominent clusters on the India-Nepal border and the India-Bangladesh border identified as hot spots for illegal endangered wildlife trading. Consequently, stronger enforcement efforts in India have led to a displacement of crime to neighbouring Nepal, especially in western parts of the country. To make matters worse, the threat to tigers has been amplified by cybercrime involving sellers attempting to sell items on the internet, as well as captive breeding.

Key to effective enforcement is collaboration at international and regional levels. The use of the anti-money laundering law in illegal wildlife trade cases is also highly commendable as there are clear indications of transnational organized criminality involved.

Pitting the profiteering gang making lucrative gains against the underfunded, mostly uncoordinated national and international enforcement seems like a classic case of David and Goliath. However, the longer it takes to tighten policies and strengthen enforcement, the more likely it is that we will witness the extinction of this majestic species in our lifetimes. The collective effort to save tigers cannot rest at policy and enforcement. All parties involved need to take advantage of technological advancements, reach expansion through social media, and access to more education to make all communities aware of the urgent need to coordinate efforts and to push forward in the battle against poaching. The fight to save the tiger has to continue until the last tiger is standing or when they are permanently off the endangered list. With concerted effort and a bit of luck, it will hopefully be the latter.