Thousands of Rohingyas fled the Rakhine state of Myanmar, having already endured violence in all manner and form – witnessing family members and loved ones killed, tortured, raped and seen houses burnt to the ground. Further south of the Indochina Peninsula, the 32-year iron fisted rule of Cambodian premier, Hun Sen continues to take its toll on the civil liberties of regular Cambodians. An independent daily was shut down in the government's effort to curb the freedom of information, while the opposition leader, Kem Sokha, was ruthlessly taken away from his home, as his party continued to gain traction amongst the Cambodian masses.

Over at Jalan Sisingamangaraja of Jakarta, officers, diplomats and regular staff continue to trudge along the corridors of the ASEAN (Association of the Southeast Asian Nations) Secretariat, withstanding the drudgery of its complex bureaucracy – seemingly oblivious to the plight of their neighbours.

ASEAN’s deafening silence over the atrocities in Myanmar and Cambodia is nothing out of the ordinary. In fact, the mundane pattern is as predictable as night and day – a crisis erupts in a member state, everyone is up in arms about it, ASEAN remains quiet and it inadvertently is condemned for not “doing the right thing.”

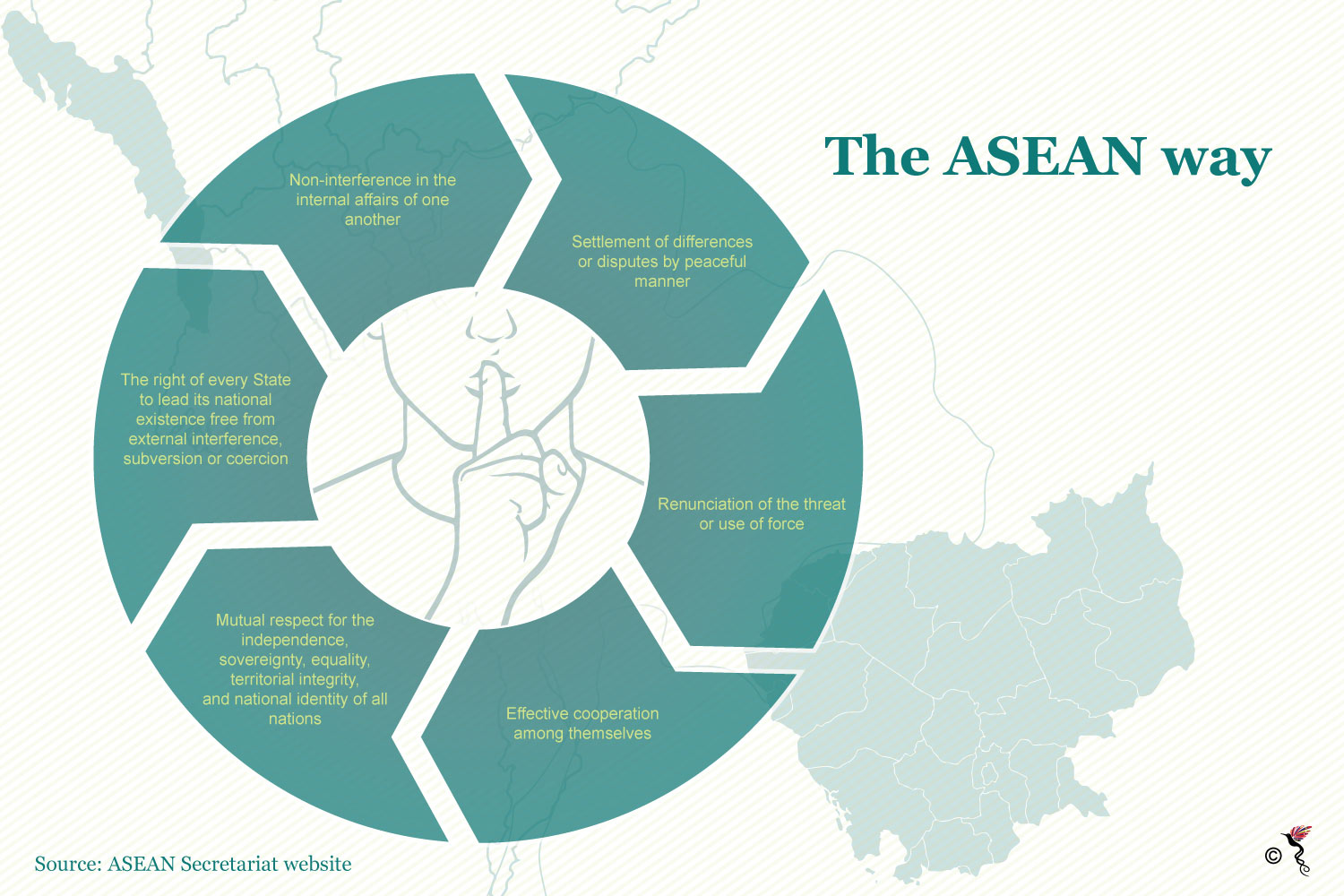

This is especially the case when it involves the actions of individual member states. Enshrined within the ASEAN Charter is the TAC (Treaty of Amity and Cooperation) – its principles have become the basis for the association’s “get out of jail card” more formally known as “The ASEAN Way”. The guiding principles of this notion is that every member state refrain from meddling in the domestic affairs of other member states, regardless of how severely member state governments impinge on the rights of their citizens.

Professor of International Relations at the University of Nottingham Malaysia Campus, William Case, in an email to the ASEAN Post stated that “ASEAN is constrained by its own principles of mutual veto and non-interference”. He added “Indeed, this has been much of the secret of the organisation’s longevity, for its asks so little of its members except that it attend events.”

Nevertheless, ASEAN cannot be faulted for the lack of trying. In 1994, it attempted to discuss Indonesia’s invasion of East Timor but that was quashed by Jakarta’s heavy-handedness. Individual ASEAN member states have also on occasion, voiced their grouses on issues pertaining to the domestic affairs of the other members.

However, the question at hand is if ASEAN is really mandated to act on the atrocities committed by the countries within the association. To answer that, one must look into the TAC. The treaty clearly spells out that it is “the right of every State to lead its national existence free from external interference, subversion or coercion” and member states should observe “non-interference in the internal affairs of one another”.

The six fundamental principles contained in the 1976 TAC (Treaty of Amity and Cooperation) in Southeast Asia.

These very principles are enough to vindicate ASEAN for its inaction and relegate the organisation to uselessness in the event of a member state acting belligerently against its people. Such thinking, nevertheless, falls short of understanding ASEAN’s endeavour at an international stage. The association has much to prove to the world as it’s made up of a motley bunch of countries – illiberal democracies, a monarchy, socialist republics and junta states.

Such hindsight is apparent in the creation of the AICHR (ASEAN Intergovernmental Commission on Human Rights), inaugurated in 2009 as a consultative body to the association. In 2012, the AICHR drafted the ASEAN Human Rights Declaration which was adopted unanimously by all 10 nations.

“On the one hand, the ASEAN Human Rights Declaration goes beyond the Universal Declaration on Human Rights by including rights to safe drinking water, sanitation, sustainable environment and the right to development. On the other hand, it falls short of international standards in not having clauses of freedom of association for example,” said Champa Patel, Head of Asia at the London based Chatham House in an email reply to The ASEAN Post.

At this juncture, there are several things to consider. ASEAN is known for its stifling decision-making process, yet it has shown commitment towards human rights via the formation of the AICHR. The ASEAN Declaration of Human Rights, at only five years, is a relatively new initiative and like most international treaties, is non-binding, making it that much more difficult to compel states to abide by its principles.

The task at hand is not getting the world to agree on an issue, but getting a regional grouping of 10 states which share almost similar customs, heritage and borders with one another, to commit to an internationally recognised standard of human rights which would lift the bad light cast upon the organisation thanks to existing poor standards of human rights. If ASEAN is adamant on sticking to its normative ways and consensus decision-making process, then these methods must produce positive results for the over 600 million citizens living in ASEAN nations.

As Patel mentioned, “it is critical these regional norms continue to develop over time, do become binding on member states of ASEAN and become more aligned to international standards”.

For ASEAN to give up on non-interference is a double-edged sword. On one hand, it is this "rule" that has kept the association from falling apart. On the other, this has become the reason for the "reactive" nature of the association where it has often reacted sluggishly in issues concerning the freedom and liberties of the ASEAN people. It will continue to do so until some manner of middle ground is found.