Democracy is under threat in Cambodia. In the run-up to the general elections next year, longstanding Cambodian Prime Minister, Hun Sen recently closed down several media outlets operating within the country. Opposition leader, Kem Sokha was arrested without a warrant from his home in what his daughter called “a move to cripple the CNRP (Cambodia National Rescue Party),” Cambodia’s leading opposition party.

Elections in Cambodia have been nothing more than a formality for Hun Sen and his party, the CPP (Cambodian People’s Party). He has been the leader of the government for the past 32 years and has recently claimed he wished to continue as Prime Minister for the next decade.

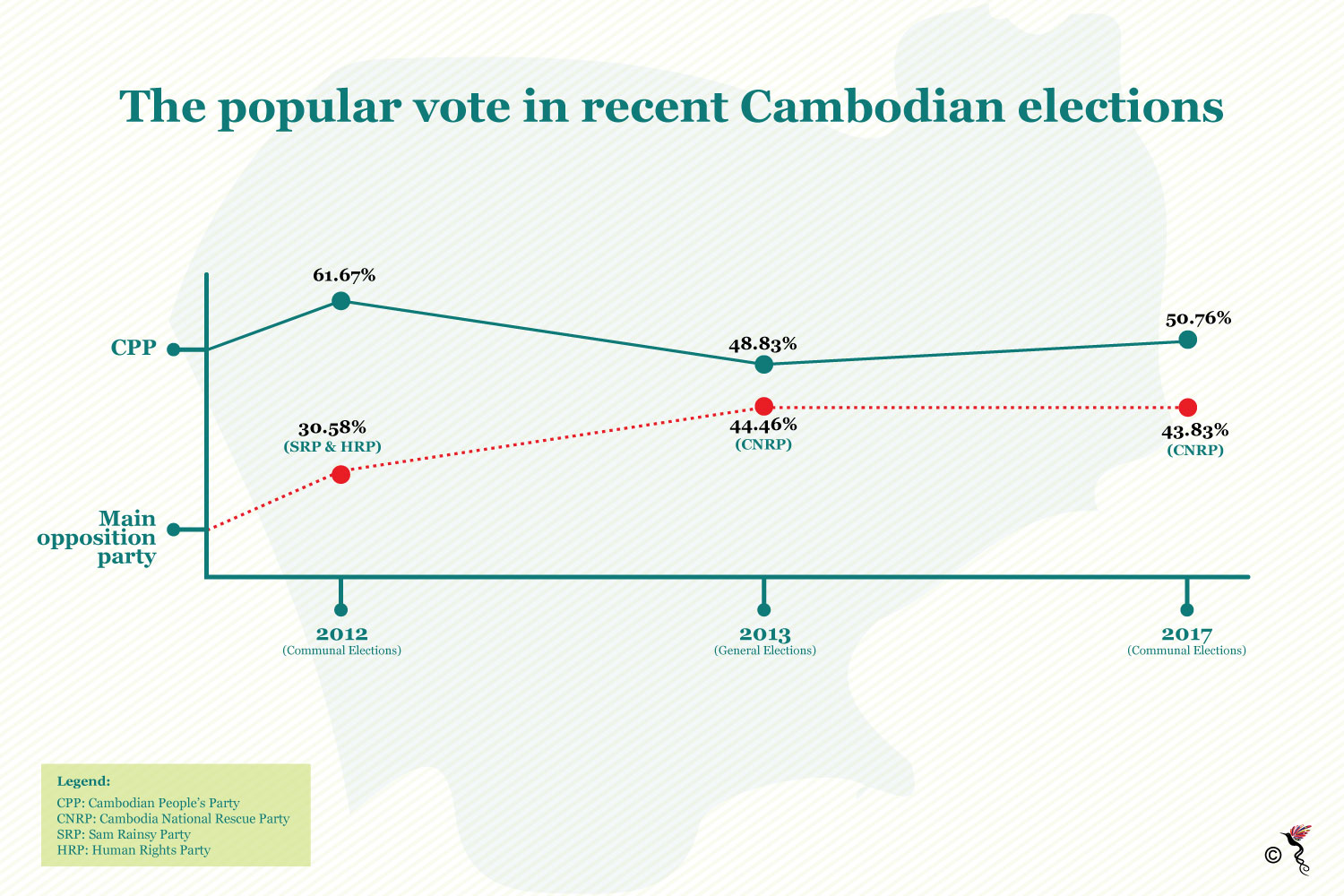

What could halt his authoritarian rule is a stronger opposition and that seems to be the case for Cambodia as the June 2017 communal elections results have demonstrated. The CNRP’s saw significant increase in the number of communal seats won from the previous elections in 2012 when it contested separately as the Sam Rainsy Party and Human Rights Party. Using this results as a stepping stone, the CNRP seeks to overthrow the rule of the CPP in the coming elections.

The communal elections have often served as a barometer to measure the success of a political party in the general elections.

The popular vote in recent Cambodian elections from 2012- 2017

Given the recent Cambodian political climate, it is difficult to gauge how voter sentiments would manifest in the elections next year. According to the Associate Professor of Diplomacy & World Affairs at Occidental College of Los Angeles, Sophal Ear, voters would vote their conscience if they are confident their vote is a secret and are not arm-twisted to vote for a certain party. However, right now Cambodians are split between those who have been emboldened by the crackdowns and those who are intimidated by it.

“When people are scared its fight-or-flight. The emboldened voter is in the fight category. Everyone else is in the flight category, and that means bowing to power, whether right or wrong, for the sake of survival,” he said in an email reply to The ASEAN Post.

Cambodia uses a closed list PR (proportional representation) system, as opposed to "the winner takes all", first past the post system. In such a system, voters vote for the party of their choice and the results are then translated into seats in the National Assembly following a “party list”.

Such a system would ensure minority representation in the parliament of Cambodia. However, voters cannot pick the candidates that enter the National Assembly as only party leaders decide the names that go into the “party list”. The members of parliament are forced to strictly toe the party line for fear of being dropped out of the list in the future. Representatives are hence logically inclined to be more responsible towards the party and its leaders as compared to the voters, concentrating more legislative power into the hands of those in the higher echelons of the party.

According to a report on electoral reform published by the Asia Foundation in 2014, this system “is less effective in developing democracies, where parties are often based on historical, geographical or ethnic affiliation rather than a particular ideology; and often lack effective mechanisms for internal party democracy.”

It is this system which has ensured Hun Sen’s continued 32-year dominance in Cambodia, there is little incentive for reform and he will make sure that he continues to win elections to further cement his rule in the country. It is no surprise then that a growing number of voters are dissatisfied by his practices and are beginning to swing to the opposition. He cannot afford to lose the elections for fear that his legislative superiority would be snatched and he will be rendered powerless.

The results in June signalled a shift in the Cambodian citizenry but that shift was met with oppression by Hun Sen’s regime. Only time will tell if democracy in this developing state will continue to be bastardised or will one day see better days.