Cambodian Prime Minister, Hun Sen is on an unstoppable onslaught. Communal elections in June this year have shown that his ruling CPP (Cambodian People’s Party) is fast losing its foothold amongst voters. Supporters are leaving his party in droves in favour of the opposition CNRP (Cambodian National Rescue Party) ahead of the general election slated for next year.

But Hun Sen is having none of this. In one fell swoop, he expelled a US-backed NGO and sent their foreign staffs packing, shut down a longstanding English daily, several radio stations and most infamously, arrested CNRP leader, Kem Sokha at his home in a commando style operation.

His actions sent shudders throughout the fledgling democracy. The outpouring of criticism and condemnation of his action from the likes of Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch did little to dent his pursuit to wipe out his opposition.

“Hun Sen has been able to enjoy free-world endorsement while maintaining a charade of democracy. It's a one-man ruling subjecting the country as private ownership of a few elite families,” said Monovithya Kem, daughter of Kem Sokha and a fellow opposition parliamentarian when contacted by The ASEAN Post.

A flawed political system

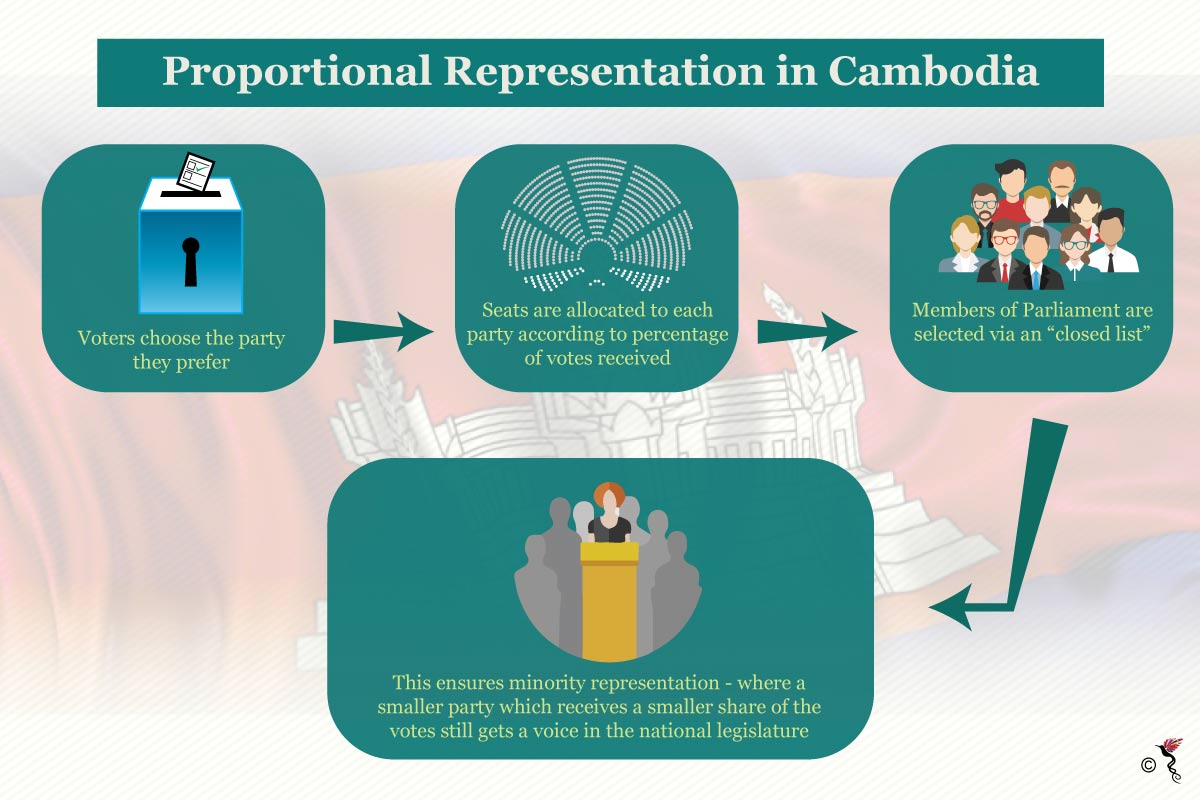

Hun Sen’s dictatorial attributes could be traced to the political system of the country where elections are characterised by the proportional representation system which follows a closed party list model. Voters are presented with a choice of political parties to choose from. Seats are then allocated according to the percentage of votes received by each party. This ensures minority representation as smaller parties and single-issue parties would have their voices heard at a national level.

Cambodia’s proportional representation electoral system.

The parliamentarians who go on to fill the seats at the national assembly are chosen from a party list. Because it’s a closed list, voters cannot choose the individual who would represent their constituency. They only have the option to pick the political party of that individual.

“Since MPs themselves were not elected as it is the party which is elected, they can potentially be dismissed from the party automatically, forfeiting their seat to anyone else the party names,” remarked Sophal Ear, Associate Professor of Diplomacy & World Affairs at Occidental College of Los Angeles.

Herein lies the biggest drawback to Cambodia’s electoral system – it concentrates power within the leadership of the party. Because party members want to be in the party list, they would have to adhere to the party line and please those sitting in the top rungs of the party who decide the names that go into the list. Their focus now shifts away from serving the people to serving the needs of the party.

It also places the political party at the crux of governance. The highest-ranking leader of the governing party – in this case, Hun Sen – becomes the Prime Minister who is also the highest serving government official. Party and government become interchangeable entities. To go against the party or party leader will often be considered as going against the government and the wishes of the Cambodian people.

Extending control to all branches of government

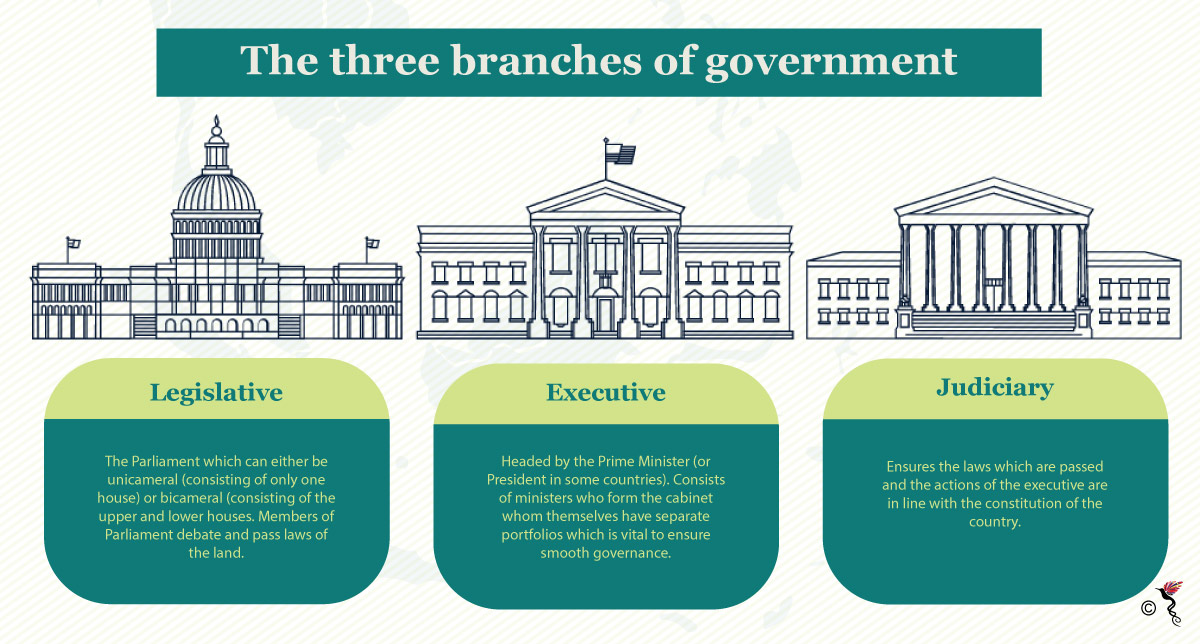

Within such a political system, Hun Sen would have no trouble extending control from the executive to the legislative and judicial branches of the Cambodian government. As party leader, he has already secured the allegiance of his MPs which he can use to pass laws at his whim. Such laws stifle the role of the judiciary so that it only looks independent on paper, but functions under the steely eyes of the executive.

The widely accepted roles of the three branches of government.

In May 2014, the Cambodian parliament passed a set of new laws governing the configuration and organisation of the courts which reinforced Hun Sen’s grip on the judiciary. The laws provided the Minister of Justice powers to supervise the judicial system, appoint judges and discipline them.

For more evidence of the courts being in the pockets of the CPP, one only needs to look at the President of the Cambodian Supreme Court, Dith Munty. Munty – who has served as President of Cambodia’s highest court since 1998 – is a member of the CPP Politburo and is the 17th ranked member of the Politburo, with Hun Sen being the top-ranking member. His personal and political connections with Hun Sen go back almost three decades. In the 1980s, when Hun Sen was seeking to get his start in politics as Cambodia’s Foreign Minister, Munty was one of his closest advisers.

Sebastian Strangio, author of "Hun Sen’s Cambodia", believes that the judiciary is also roped into the immense network of patronage that undergirds the CPP and its governance of Cambodia.

“Appointees to the judiciary are part of the same system of economic and political incentives that the rest of the Cambodian government is. When a political case comes to the bench, they will always rule in favour of those who put them there. Since the government would never appoint someone who isn’t loyal to this system, the problem just perpetuates itself,” he told The ASEAN Post in a telephone interview.

Systemic disbanding of the opposition

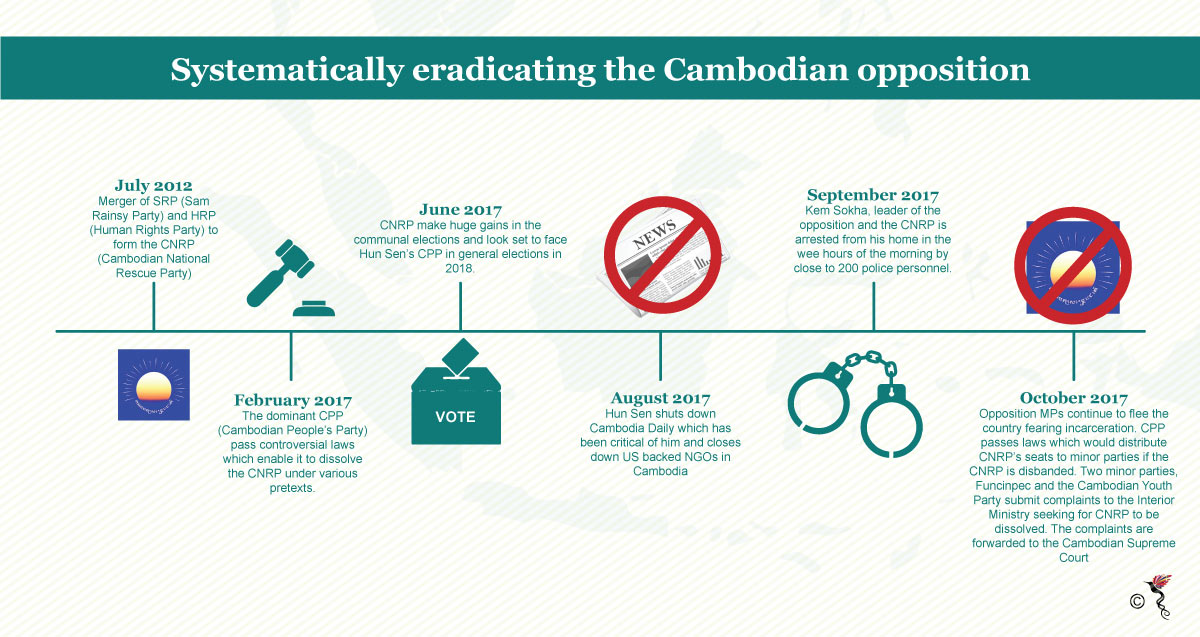

Earlier this year, the ruling government passed controversial changes to the law which would enable it to dissolve the opposition under various pretexts.

Now, with Kem Sokha behind bars, Hun Sen seems ready to move in for the kill. In an event a few days back, he lashed out at the opposition stalwart and conveyed signs that his crackdown on the Cambodian opposition is far from over.

“This will not end with Kem Sokha’s arrest,” he told a crowd of supporters in central Cambodia. His words triggered a mass exodus of opposition MPs who fled the country in fear of being imprisoned.

However, the CPP – in a bid to veil their intentions – has empowered smaller opposition parties to do their biddings. Recently, it rushed through amendments through parliament, amending laws so that in the case of CNRP’s dissolution, its seats would be distributed to other opposition parties.

The key benefactor of such a move is the royalist Funcinpec party. In the 1990s, the party led by Norodom Ranariddh served as a strong opposition to Hun Sen’s CPP but gradually frivolled away. This is Ranariddh’s last chance to retain some foothold in the Cambodian political system. In separate complaints, the Funcinpec party and another minor opposition party, the Cambodian Youth Party submitted complaints to the Interior Ministry in a bid to disband the CNRP. Subsequently, the Interior Ministry forwarded those complaints to the Cambodian Supreme Court.

The systematic eradication of Cambodia's opposition.

“The complaints submitted have Hun Sen’s fingerprints all over them. These parties are not acting independently out of desire to see the law upheld. It’s very much the case of the CPP issuing orders and these smaller parties following them,” remarked Strangio, who is a seasoned Southeast Asian analyst.

Strangio believes that that both parties have been attached to the patron-client networks of Hun Sen and the CPP are expecting to derive political and economic gain from that connection.

“In the case of Ranariddh, he has his own small network of clients and supporters but he needs a patron above him to feed his own patronage network and renew the loyalty of his own followers. So, Hun Sen to him is his best bet at the moment,” he explained.

However, the CPP insists that it is acting within the boundaries of the law. Lawyers for the CPP continued blaming Kem Sokha for colluding with foreign entities to topple the government – a claim widely held by many observers as politically motivated.

“There is strong and sufficient evidence for the Supreme Court to dissolve the CNRP. If we keep the CNRP, it will lead to the destruction of the nation so we must prevent it," said Ky Tech, one of the lawyers as quoted by AFP.

Future of Cambodian democracy

Cambodia’s political future is looking undoubtedly bleak. It is fair to assume that Hun Sen's end goal is to consign the CNRP to oblivion. However, it may also be in his best interest to weaken the CNRP so that it cannot not mount an effective challenge to the CPP in the upcoming general elections.

“The question is whether the CPP can derive enough political benefit from the current situation and allow the CNRP to continue on life support after the next election. I think the CPP would prefer the cosmetic presence of the CNRP,” said Strangio.

He added that the problem will then be maintaining the balance between allowing the CNRP to exist and ensuring it doesn’t shore up more support and subsequently supplant the CPP.

“It’s a difficult balance to maintain and the CPP might very well decide it would be easier to eliminate the party altogether and deal with the criticisms that are likely to follow,” he concluded.

Under Hun Sen’s regime, the three separate branches of government – the cornerstone of modern day democracy – have been corroded and are now wrapped tightly around his fingers. The remaining bastion of Cambodian democracy as embodied by the CNRP seems to be slithering away to obscurity with every autocratic move made by Hun Sen's government. Cambodians and the international community have since been watching the bludgeoning of democracy continue to unfold within the country’s borders.

How much longer can the country endure this?