ASEAN is no stranger to the plethora of acronyms that make up the names of its organs and initiatives – ARF, AICHR, SEOM, AMM, ADCFIM, just to name a few. However, one in particular is likely to pique the interest of many as it's set to be discussed heavily on the side lines of the ASEAN Summit – the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP).

So far, the 16 participating countries have concluded 19 rounds of negotiations by the end of July 2017 following negotiations which began in 2013. If RCEP is successfully ratified and its initiatives implemented, it stands to be the largest trade deal since the General Agreements on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) Uruguay Round in 1994 which established the World Trade Organisation (WTO).

RCEP is important to the region for multiple reasons. Mainly, it further strengthens existing free trade agreements (FTA) between ASEAN and its six FTA partners. Its primary agenda covers trade and investment liberalisation, economic and technical cooperation, intellectual property rights, competition policy and dispute settlement.

According to a briefing paper published by Singapore based ISEAS – Yusuf Ishak Institute, authors Malcolm Cook and Sanchita Basu Das wrote that once completed, RCEP would be able to address the main issues faced by the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) vis-à-vis regional economic integration.

“APEC is a not a trade negotiation forum and can only facilitate any future Asia-Pacific free trade talks. ASEAN, as shown by RCEP negotiations, can be an Asia-Pacific trade negotiation forum,” Cook and Das wrote.

There is haste on the side of Beijing to want to quickly conclude RCEP negotiations by the end of this year. However, such an ambition is too far-fetched. As Philippine Secretary of Trade, Ramon Lopez once commented on the conclusion of RCEP – it “can take many years if the participating countries will not change their position on the matters being discussed.”

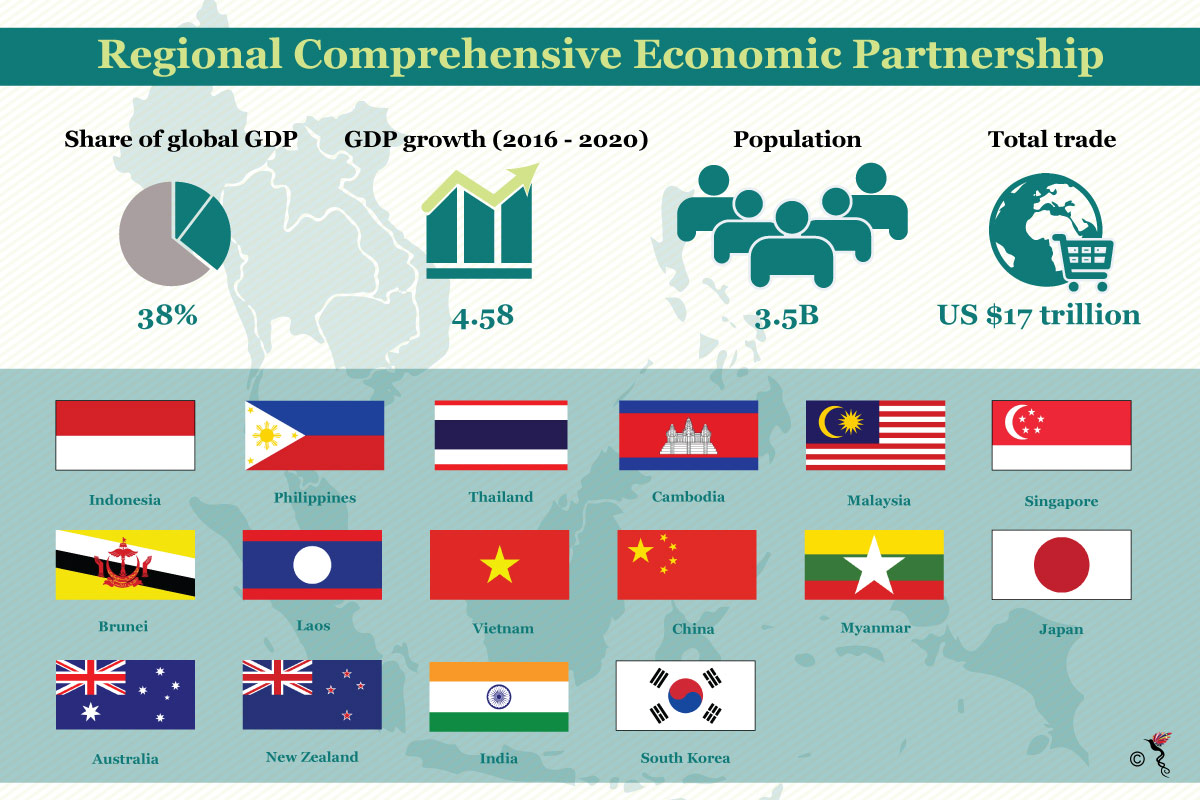

RCEP member states and data.

Beijing’s urgency often paints the picture of RCEP being a Chinese trade deal that is trying to carve out importance for itself amidst the absence of the previously US-led Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). However, contrary to popular belief, RCEP is in fact ASEAN-led and not an initiative spearheaded by China.

What RCEP represents is a nod to free trade, in line with China’s embrace of the liberal internationalist economic order. This is in stark contrast to the more protectionist foreign trade policies of the Trump administration which could be the reason why both trade deals seem pitted against each other – when it isn’t.

The TPP, nevertheless, is not completely dead in the water with Japan picking up the pieces and leading the remaining TPP-11 – a move which China welcomes.

According to Sourabh Gupta, Senior Fellow at the Institute of China American Studies, Beijing is in fact warier of protectionist outlooks in the development of international trade.

“What China fears instead is the creeping protectionism in the developed world on trade and investment issues. To the extent that significant trading economies remain open and receptive to free trade, including through TPP-11, China will be by-and-large accepting and tolerant of this development,” he said.

Echoing his sentiments, Chris Nixon, Senior Economist at the New Zealand Institute of Economic Research stated in an email response to The ASEAN Post that, “the Chinese are in the prime position – they have played a consistent trade policy game and have publicly stated that any deal that is WTO consistent will benefit all.”

With ministers, senior diplomats and the likes present at the ASEAN Summit this year, the talk of free trade deals will likely be a hot topic of conversation – a welcome proposition for believers in neoliberal free trade economics. Meanwhile, the naysayers look on sceptically.

Recommended stories: