From rivulets to regionwide river channels, the Southeast Asian region hosts dozens of rivers. The most known river in Southeast Asia is the Mekong River – spanning five countries in the region itself.

The Mekong, which is also the 12th longest river in the world is known to be a major water source for drinking, fishing and agricultural needs for millions of people. What many do not know about it however, is that it is also a dumping ground for garbage and waste deposits making it to be one of the most polluted rivers in the region.

River pollution is nothing new. In fact, the pollution that is currently taking place in the region has stemmed from centuries ago. These water resources in Southeast Asia are under intense pressure because of population growth, urbanisation and climate change.

Rapid economic development and urbanisation has resulted in degradation and depletion of natural resources, including water and related ecosystem services. Many rivers in the region are highly polluted with domestic, industrial and agricultural waste thus causing the Water Quality Index (WQI) to reach unsafe levels.

In this picture taken on March 18, 2017, a worker collects garbage from the Marilao River in Bulacan, north of Manila, the Philippines. (AFP Photo/Noel Celis)

Most polluted rivers in Southeast Asia

The Marilao river flows through Metro Manila in the Philippines. Its pollution is one of the major causes of concern for both, the government of Philippines as well as for the world. Hazardous non-recyclable objects such as plastic bottles and rubber slippers, amongst others are commonly found floating on the river. Moreover, toxic industrial waste products are also dumped into the river each day and household garbage is also discarded in huge quantities.

Based on the Institute for the Advanced Study of Sustainability’s Policy Brief report, pollution levels in Metro Manila’s rivers are so high that “they could be considered open sewers.” The main cause is the untreated residential waste that flows directly into the waterbodies. According to official statistics, only 20–30 percent of the city’s households are connected to a sewerage system. The remaining 70 percent of households have septic tanks, which in many cases leak human waste into underground aquifers.

Another headlining river in the region is the Citarum river that flows through the Indonesian province of West Java. The Citarum river is an important resource which aids in agriculture, water supply, industry, fishery, and production of electricity.

However, it is now filled with tonnes of domestic and industrial waste and mercury level in the river is 100 times more than the legal amount. Apart from that, there are also three hydroelectric power-plant dams along the river but with the exacerbating issue of pollution, these plants will not be able to function. Hence, causing the surrounding communities to live without electricity.

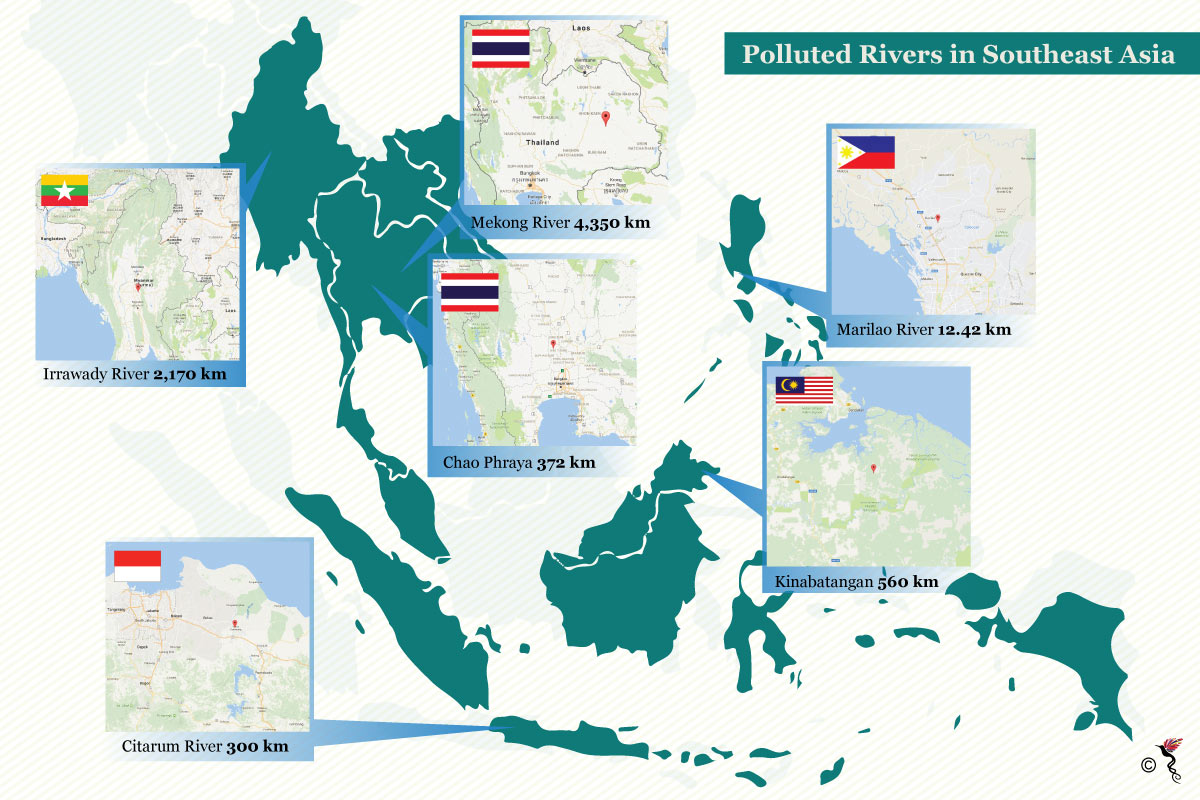

Polluted rivers in Southeast Asia.

The other rivers in the region that are facing pollution include the Irrawady river in Myanmar, Chao Phraya in Thailand and the Kinabatangan river in Malaysia. Causes and effects behind the pollution are similar between these and other rivers in the region.

Yasmin Rasyid, biologist and President of Ecoknights, stated in a phone interview with The ASEAN Post that the factors of river pollution include “heavy metal pollution and lack of enforcement on the issue of discharges from industries, encroachment of riverbanks and illegal sand mining activities, poor development along riverine areas, discharges of organic and solid waste into waterways.”

How can these rivers be recovered and rehabilitated?

Some governments are already looking into the matter seriously. For example, the Malaysian government’s intention of turning the rivers of the federal capital into an attraction by 2020 is being materialised with the cleaning works under the River of Life (ROL) project underway. The river-cleaning project throughout a 110-km stretch is now 86 percent completed and will soon be safe enough for recreational purposes.

The cleaning works involved numerous phases, such as the installation of trash traps, and the upgrading of flood catchment ponds, sewage treatment plant as well as sewerage systems.

When asked about what else can governments do to curb this issue and to make the region’s rivers clean again, Yasmin explained that “we need to step up on enforcement and increase the penalty for any violation of the river areas.”

“We also have too many government agencies handling different aspects of river management which I think needs to be redesigned again to ensure that these overlaps can be addressed to ensure integration and harmonization of actions by the government agencies,” she added.

The ‘Policy Brief’ report suggests that in order to tackle this issue and to foster an effective approach for sustainable urban development in the region, policymakers in collaboration with the private sector and the international donor community must adopt an integrated approach for protecting urban waterbodies, including by developing relevant legal frameworks and enforcement mechanisms.

There is also a need to initiate comprehensive studies on valuation of water-related benefits. The monetary value of water quality improvements is a useful variable in cost-benefit analyses of water quality-related policies, in both the public and private sectors.

Last but not least public awareness campaigns must be promoted through campaigns and education as well as transparency through public outreach programmes.

Recommended stories: