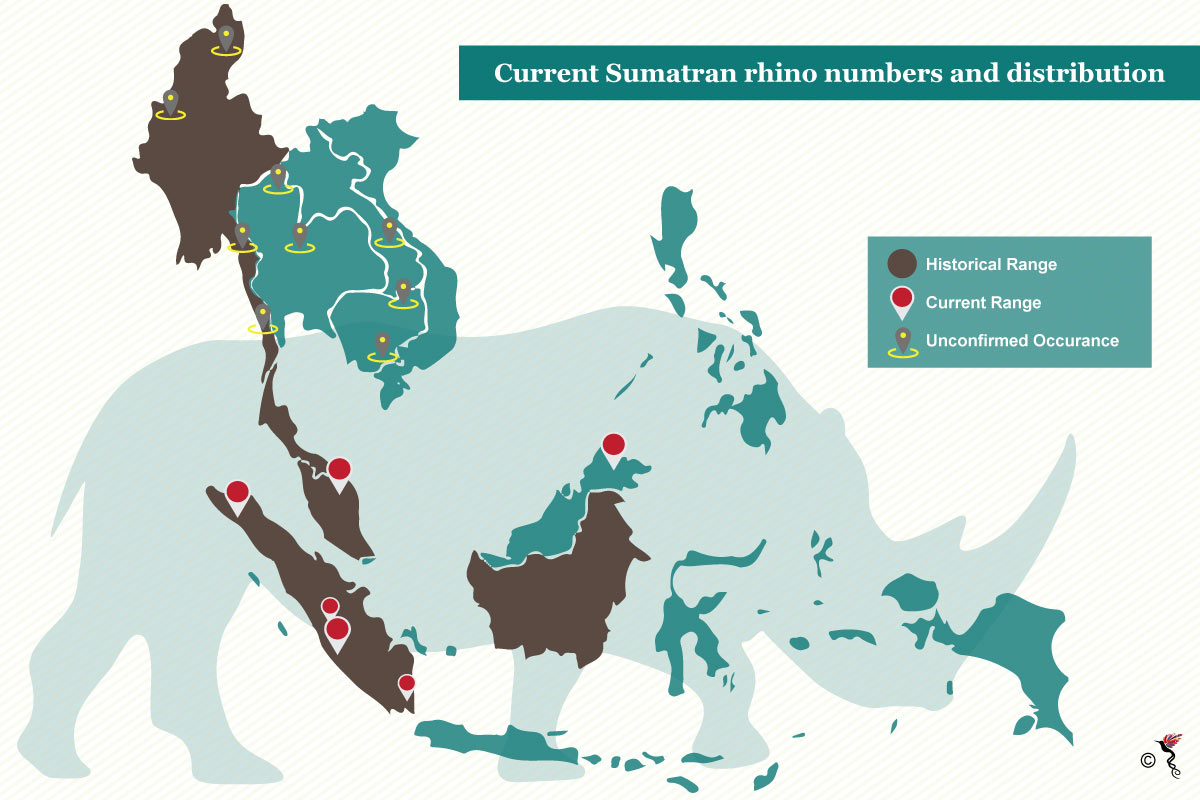

While the Sumatran rhino, Dicerorhinus sumatrensis, once roamed the foothills of the eastern Himalayas in Bhutan and India, through Myanmar, Thailand, possibly to Vietnam and China, and south through the Malay Peninsula, the species in now found in diminutive populations on the island of Sumatra in Indonesia.

These scattered populations are mainly confined to Gunung Leuser, Kerinci-Seblat and Bukit Barisan Selatan National Parks. A few are also reported to be found in Kalimantan.

The species was officially declared extinct in the wild in Malaysia in August 2015.

Overall, Sumatran rhino numbers are thought to have at least halved between 1985 and 1995, with the total number of individuals now estimated at fewer than 100, given a best-case scenario although most experts think that there might only be 30 left throughout the region. However up until now, there has been no official data on the Sumatran rhino population.

Source: International Rhino Foundation

Threats to the Sumatran rhino

Like every other threatened animal in the region, habitat loss due to forest conversion for urbanisation development is the biggest factor pushing the Sumatran rhino towards extinction.

Most populations are very small and isolated - and may not be sustainable unless connecting corridors are built. Bukit Barisan Selatan National Park in Sumatra in Indonesia, which is now estimated to have the largest single population of Sumatran rhinos, is still losing forest cover due to conversion of forest for coffee and rice production by illegal settlers.

Sumatran rhinos are known to use logged areas where there is an abundance of regenerating plants. However, the construction of logging roads makes areas more accessible to poachers.

Poaching is of course another major threat to the species. Rhino horns are still used in traditional Asian medicine for the treatment of a variety of ailments, even though the trade is illegal and despite efforts to reduce demand. In Vietnam, rhino horns are bought as a status symbol to display one's success and wealth.

According to World Wildlife Fund (WWF), another threat comes from the species’ declining genetic diversity. No single Sumatran rhino population is estimated to have more than 75 individuals, making them extremely vulnerable to extinction due to natural catastrophes, diseases and inbreeding.

What is the Indonesian Goverment doing?

As the numbers are rapidly decreasing, serious measures must be taken in order to prevent exacerbations of the situation.

To date, the Indonesian government has not acted fast enough to curtail the bleeding of the Sumatran rhino populations or to establish a population that is truly an insurance against extinction.

Since no rhinos can be taken from the wild without the governments approval, the rhinos are considered government property. Hence, it is imperative that the government takes immediate action to maintain and increase the population of the Sumatran rhinos.

The conservation efforts by the Indonesian government has seen multiple delays in recent times. Despite having meetings, declarations and even 12-point plans, still no action has been taken.

A meeting was held in May 2017 in Jakarta where a consensus was reached – more rhinos to be captured from the wild and placed in the Sumatran Rhino Sanctuary (SRS), where a captive-breeding program is underway. However, after six months, there is yet to be any action taken.

In an e-mail correspondence with The ASEAN Post, Acting Regional Director for Traffic in Southeast Asia, Kanitha Krishnasamy stated that “government, research institutions and NGOs can help monitor and track trade” the population of the declining Sumatran rhinos.

When asked about the environmental impact behind this decreasing population size, she stated that,”the broader environmental problem is one of security - about how a network of individuals all the way from the local level to an international one, conspire to conduct unlawful activities that contribute to the serious decline of a critically endangered species; pushing them one step closer to extinction in the wild. “

Recommended stories: