Amidst the Papal visit to Myanmar, one issue still looms – the humanitarian crisis unfolding at the Rakhine State in Myanmar near the Bangladesh-Myanmar border.

Rohingya refugees who return to Myanmar following a Bangladesh-Myanmar repatriation agreement will initially have to live in temporary shelters or camps, Dhaka said Saturday.

"Primarily they will be kept at temporary shelters or arrangements for a limited time," Bangladesh Foreign Minister A.H. Mahmood Ali told reporters in the capital Dhaka.

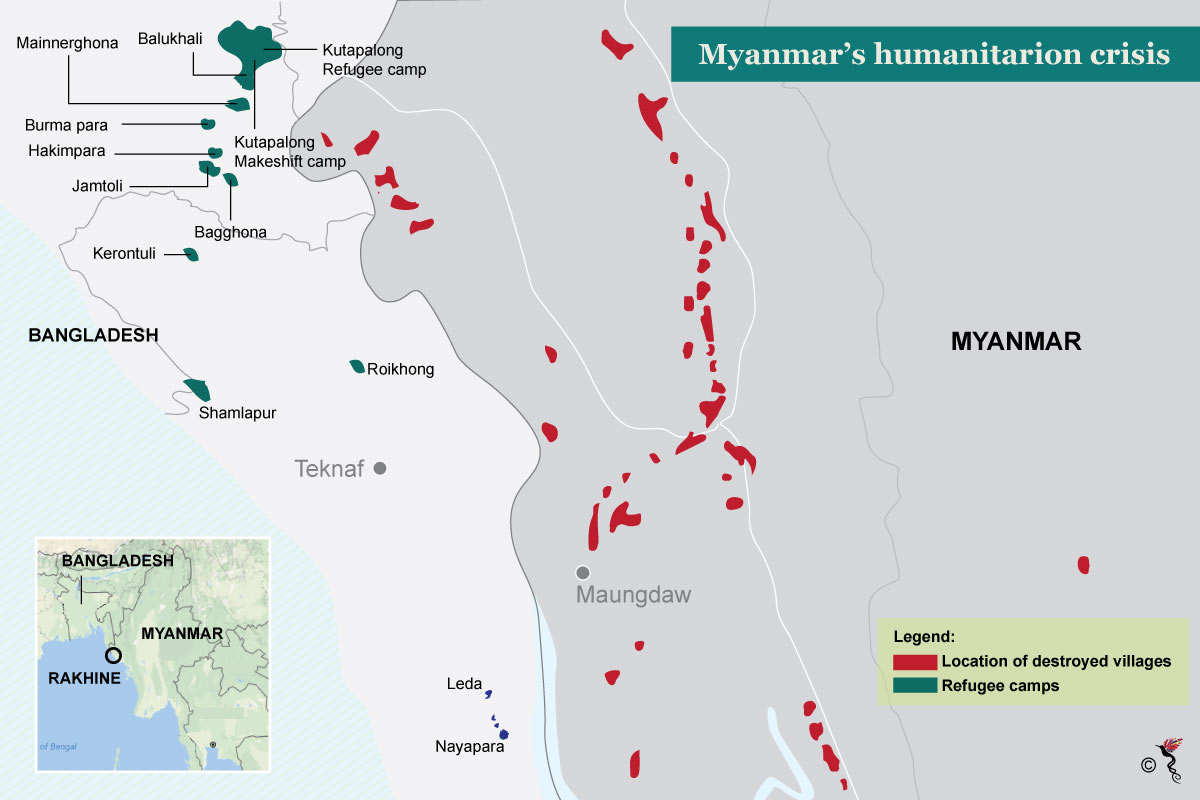

The United Nations says 620,000 Rohingya have fled to Bangladesh since August and now live in squalor in the world's largest refugee camp after a military crackdown in Myanmar that the UN and Washington said clearly constitutes "ethnic cleansing".

Location of refugee camps in Bangladesh (Source: AFP)

Under the agreement, Myanmar "would restore normalcy in Northern Rakhine (State) and to encourage those who had left Myanmar to return voluntarily and safely to their own households" or "to a safe and secure place nearest to it of their choice".

Refugee return is slated to begin within two months and a joint working group will be formed over the next three weeks to see through the repatriation.

Refugees would have to fill up a form and state personal details, those of their family members and previous addresses in Myanmar. They must also sign a statement of voluntary return before being repatriated.

Myint Kyaing, Permanent Secretary of Myanmar’s Ministry of Labour, Immigration and Population stated that Myanmar would take in refugees with proper government-issued identification papers.

“We are ready to take them back as soon as possible after Bangladesh sends the forms back to us,” he added.

Talks of return 'clearly premature'

In response to the bilateral agreement, Amnesty International’s Director for Refugee and Migrant Rights, Charmain Mohamed, said that talking about refugees returning is “clearly premature” when there are still many Rohingya refugees trickling into Bangladesh daily.

“Myanmar and Bangladesh have clear obligations under international law not to return individuals to a situation in which they are at risk of persecution or other serious human rights violations,” he said in a statement released by the London based rights group.

Echoing that sentiment, the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) released a statement that “it is critical that returns do not take place precipitously or prematurely.”

“At present, conditions in Myanmar's Rakhine State are not in place to enable safe and sustainable returns. Refugees are still fleeing, and many have suffered violence, rape, and deep psychological harm. Most have little or nothing to go back to, their homes and villages destroyed,” UNHCR added.

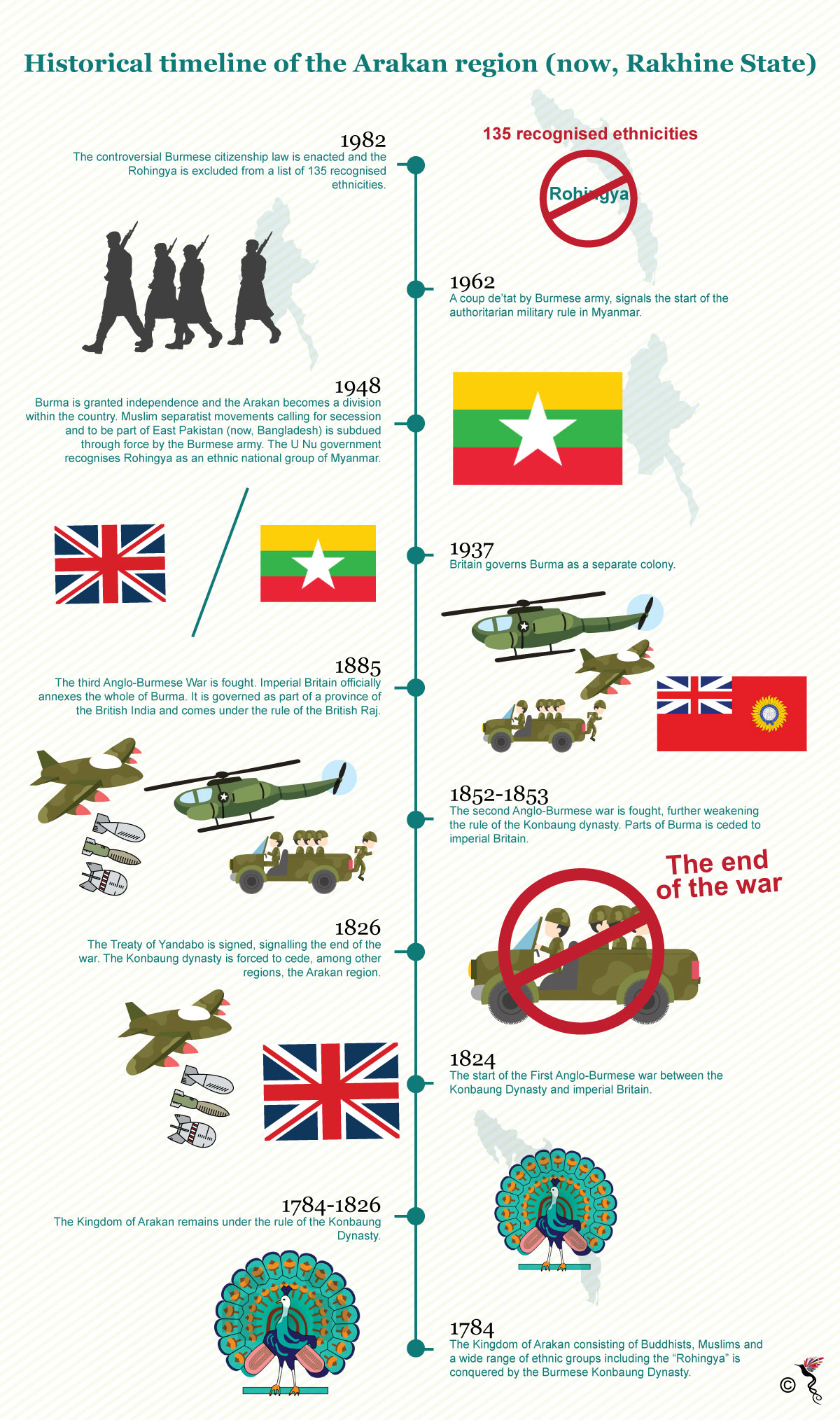

The problem here is that these Muslim refugees are not legally recognised by the Myanmar government as citizens of the country due to the 1982 Citizenship Act. The law only recognises 135 ethnicities as citizens of Myanmar and the Rohingya have been excluded from that list.

Timeline of the history of the Arakan Region in the present day Rakhine State of Myanmar.

According to a recent report by Amnesty International, the Rohingya have suffered systematically from lopsided and discriminatory government policies. They are deprived of identity and residency documentation by the state. It is near impossible for Rohingya families to register newborn babies and some run the risk of being deleted from official residency lists if they aren’t present during mandatory annual “household inspections.”

“Without proof of residence it is extremely difficult to acquire any form of citizenship in the future, and for those who have left Myanmar, whether they were driven out by violence or left in search of education and livelihood opportunities, it means it is virtually impossible to return,” the report stated.

Will the Papal visit change anything?

Pope Francis is already in the crosshairs of Buddhist ultra-nationalists after he expressed sympathy for the plight of the Rohingya – even going as far as calling them his “brothers.”

His public comments would be closely monitored for any mention of the “R-word.” Myanmar’s government have for long, refrained from calling them Rohingya – insisting that they are in fact Muslim Bengalis.

According to Agence France Presse (AFP), Myanmar’s Catholic leaders have advised the Pope not to use the term “Rohingya”, a path also taken by Myanmar’s de-facto leader, Aung San Suu Kyi in a bid to avoid triggering backlash from Buddhist nationalists, a powerful political bloc.

Myanmar's Buddhist clergy have taken steps to rein in controversial members. Radical Islamaphobic monk, Wirathu has been banned from giving sermons for a year – albeit with little enforcement – and a few days before the Pope’s visit, another prominent ultra-nationalist abbot, Parmaukkha, was detained over anti-Rohingya protests he organised last year.

But those moves have done little to draw the toxicity from anti-Rohingya hatred pinballing across social media in the form of rants, memes and grotesque cartoons.

This hyper-nationalism stretches back to Myanmar's British colonial past, when the mass migration of people from South Asia caused economic and social tensions, according to Burmese historian Thant Myint-U.

"It created a sour, defensive nationalism, and remains at the heart of Myanmar's political DNA," he said.

Analysts warn the animus threatens to unpick fragile democratic gains in the former junta-run country and have chastised Suu Kyi for failing to use her moral authority to defend the Rohingya.

The Nobel laureate has avoided dangerous political territory by not condemning the army crackdown that sparked the refugee crisis.

The Pope's visit will test that intransigence.

Additional reporting by Agence France Presse (AFP).

Recommended stories: