One night during Darwan’s second term, a farmer named Marjuansyah, who lived in the village the bupati had grown up in, had an unsettling encounter with the police. For two years he had nursed a small patch of oil palm east of Lake Sembuluh, and hundreds of saplings were now close to bearing fruit. But his land also fell within an area licensed to one of the companies Darwan’s son Ruswandi had sold to Triputra.

The police told Marjuansyah that they had come on company business. Triputra, they said, would pay him five million rupiah, around US$550, for each of his nine hectares. The cash would not last long, while the palms he had cultivated could provide him an income for the rest of his life, a security net as he entered old age. He did not want to sell, but felt uneasy about refusing a firm whose approach had been made through the police. Hoping to put them off the trail, he later told them he could accept no less than twice what they were offering.

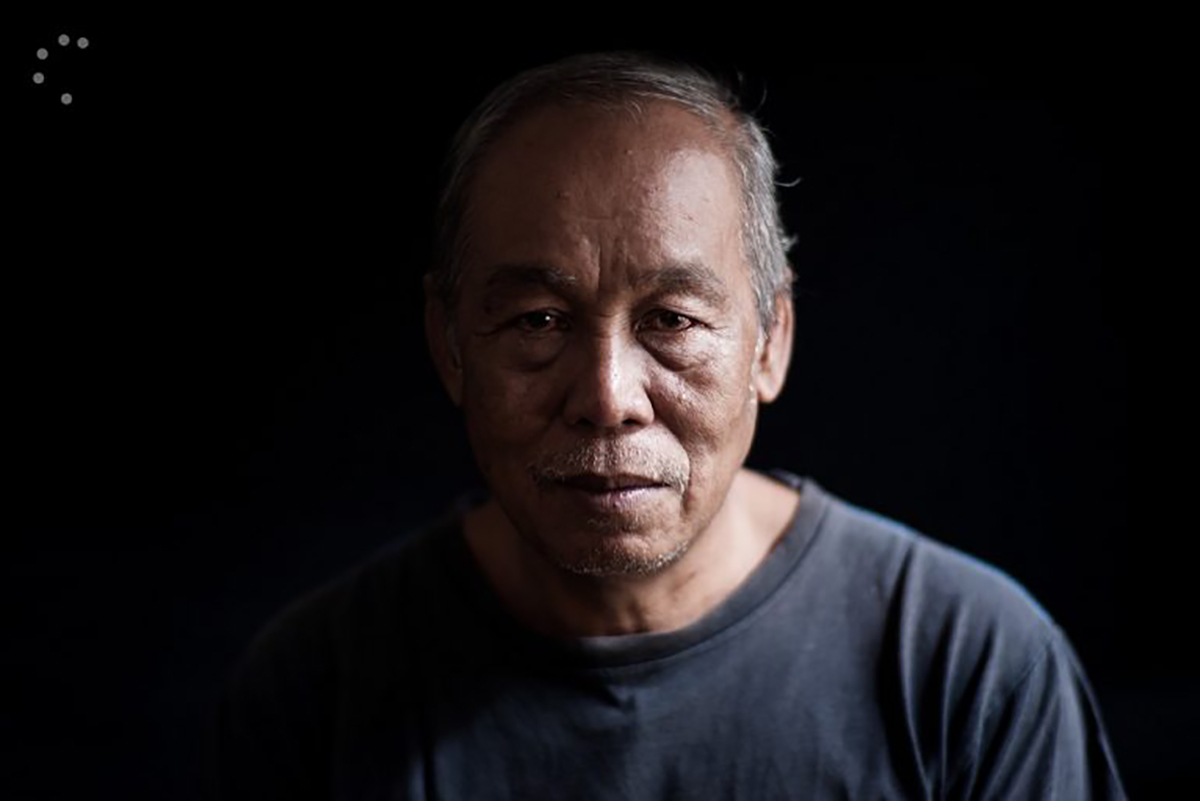

Instead, he told us, Triputra found other people to stake a false claim to his land, and paid them for it. Pliant local officials vouched for the transaction. The company ran bulldozers over his farm – smallholder oil palm is typically inferior to corporate-grown trees – and demolished a cottage he had built. “I reported it to the police,” Marjuansyah told us at a friend’s home in the village, clutching a blurry photo of his former dwelling. “But there was no reaction.”

Marjuansyah, with a photograph of the hut destroyed when his land was taken by Triputra Agro Persada.

A similar fate befell many of the people of Seruyan as plantation firms advanced through their farmlands and the surrounding forests. It was not uncommon for the companies to offer some money for their land, presumably in the hope of heading off resistance. But it was not, as Marjuansyah found, a negotiation, and there was little option to refuse.

The farmers were at a disadvantage because the state did not recognise their land rights. Some had certificates issued by village chiefs but these were legally precarious compared to the companies’ state-sanctioned licenses. As Marjuansyah also found, they could be forged or manipulated. Many land claims were overlapping, a situation that had not troubled village life when there was no commercial pressure on land, and they could be resolved through customary law. When the companies arrived, they ignited and exploited these disputes, buying land from whomever would sell it first.

The presence of the police in negotiating with Marjuansyah was not an isolated incident. In other cases, they took a clear and partial position in protecting the companies’ interests. A farmer named Wardian bin Junaidi told us how Triputra’s same subsidiary tore down his rambutan and durian fruit trees. His appeals to the company were ignored.

Wardian bin Junaidi was imprisoned for several months after his land was taken by Triputra Agro Persada.

“I got fed up with continually petitioning them,” he said. “So one day I went and harvested some of that palm fruit myself.” He was arrested and imprisoned for several months. “I was accused of stealing. Really, those people are the thieves. But the law is selective. It’s not for us poor people. It’s the companies that have the money.”

From the earliest days of Indonesia’s palm oil industry, the government had sought to strike a balance between ceding land to large companies capable of developing viable plantations, and ensuring that nearby communities benefited. Through the 1980s and 1990s it experimented with various models, involving both the state and private sector. Most commonly, firms were required to equip local farmers with smallholdings planted with oil palm. Just a couple of hectares of mature trees could transform the lives of an impoverished family in rural Indonesia.

The proportion of land that companies had to provide varied. Cede too much to the firms and the communities would not benefit; too little and the investment would be unappealing. By 2002 the prevailing regulation was ambiguous over how companies were to support local farmers, but clear that they had to do it. This was the regulation that gave bupatis power over licensing, and also the authority to revoke permits if companies failed to “grow and empower” local communities. In 2007 the rules became more concrete, requiring companies to provide, plant and hand over an area of smallholdings equivalent to a fifth of their license.

Every company greenlighted by Darwan was bound by these rules, but across the board they failed to comply. Into Darwan’s second term, their failure to deliver caused growing unrest.

“I was accused of stealing. Really, those people are the thieves. But the law is selective. It’s not for us poor people. It’s the companies that have the money.”

If the early land grabs were a cold hard shock, the dearth of smallholdings was a sting that lingered. Without them the communities were left out of the riches generated by the plantations, which were concentrated in the hands of the billionaires who had become the district’s biggest landowners. The villagers had lost their farms, the rivers had become polluted, the best jobs on the plantations went to outsiders seen as more skilled, and day labour picking fruit paid too little to live with dignity.

As the villagers’ protests fell on deaf ears, it became increasingly clear that Darwan was not only representing the companies’ interests, but also wielding his control over the state in support of the firms. When Triputra sparked alarm with a plan to build a processing facility upstream of Lake Sembuluh, residents who complained were met with threats from the bupati himself.

“In 2010, he came to our village for a religious event and said, ‘no one should oppose the mill or there will be trouble,” one villager told an NGO. “‘If you work in government or plantations, then you will be fired’.” Darwan reportedly installed new chiefs in villages that opposed plantations, eroding the potential for resistance through formal institutions.

At the beginning of Darwan’s second term a heavyset, outspoken man named Budiardi was elected to the district legislature with, as he described it, “a mandate to struggle for the people’s rights against the company.” Budiardi came from Hanau subdistrict, where the BEST Group had set up in the national park and in the villages around it. Yet he soon came to the view that it was futile to try to change the system from within. Darwan’s party dominated the parliament; the speaker was his nephew. “It was useless to oppose Darwan’s policies,” Budiardi told us. “The bupati controlled the parliament.”

James Watt, a stoic farmer from the lakeside village of Bangkal, had bought into Darwan’s pledge to make the plantations work for the people, before his land was taken by the Sinar Mas Group, an Indonesian conglomerate founded by the billionaire Widjaja family. “All we got was oppression,” James told us. “Clearing our land, dumping waste in our rivers. We never imagined it would be like this.” As the companies pushed forth, Darwan didn’t lift a finger. “It was always empty promises with him. I think he saw being bupati as his chance to make as much money as possible.”

As the futility of opposition through the state – village institutions, police, parliament, and bupati – dawned on the farmers of Seruyan, they began to take direct action. A man named Sadarsyah who claimed his land was grabbed by Triputra became a symbol of the unresolved conflicts in early 2011, prompting villagers to block a company road for days. Triputra accused him of fraud and reported the protesters to the police.

“It was useless to oppose Darwan’s policies. The bupati controlled the parliament.”

Meanwhile in a Wilmar subsidiary, hundreds of villagers shut down a main road into the concession. Anti-riot police had by then become a frequent sight in the plantation. When an NGO team made a research trip to one of their plantations in 2012, among the first things they saw was a soldier with an M-16 assault rifle.

The prospect of a prosecution by the KPK hovered over Darwan. The anti-graft agency visited Seruyan in 2008, following up on Marianto’s report only after the bupati was locked in for a second term. They searched government offices for data over several trips to Kuala Pembuang, the seaside district capital, according to Marianto. (The KPK declined to comment on Darwan’s case.)

At one point, they held a meeting with Darwan’s aide and a coterie of local figures, Marianto included. “Don’t just come and look around,” Marianto recalled urging them. “We hope the KPK can bring about the result desired by the people.” But as the second term wore on, the investigation seemed to go nowhere.

Nordin Abah, the activist who did his own investigation of Darwan, also reported him to the KPK. He was in contact with the agency’s leadership throughout his second term, but a case never transpired. Nordin had the option of reporting him for corruption to the police or attorney general’s office, in addition to the KPK. But he told us that would have been “pointless” – they were just as crooked as Darwan.

“All we got was oppression. I think he saw being bupati as his chance to make as much money as possible.”

Nordin also feared he could have been “criminalized”: arrested for an offense he didn’t commit. He said he received a threat against his children, sent to his phone. “Nordin, if you come here again, if you stay in Seruyan, you’d better think about your little son,” he told us, taking the voice of his intimidators. “That upset me, those threats about my son. If it’s just me no problem, but if it’s my son I’m worried.” Nordin passed away from hypertension in June this year, at the age of 47.

Toward the end of July 2011, tensions in Seruyan came to a head. Thousands of villagers from across the district descended on the seat of Darwan’s administration in Kuala Pembuang, pitching tents outside the parliament building and demanding an audience with the bupati. The protesters represented 27 villages, and had come to air the twin grievances of land grabs and the failure to provide smallholdings. One of the coordinators was James Watt, the farmer from Bangkal who had lost his land to the Sinar Mas Group. They were accompanied by sympathetic members of the local parliament, including Budiardi. The people unfurled their banners, set up a general kitchen and declared their intent to stay put until Darwan came to meet them.

A newspaper clipping from the 2011 protest. The banner reads, “Bupati don’t be afraid we only demand our rights.”

Days later, Darwan finally emerged from the door of the parliament building. Stepping out onto a raised veranda, he looked down upon the protesters surrounding it. He had deep jowls and a lopsided smile that gave him a sardonic expression. He wore his dark, button-down bupati’s shirt and a black peci, a Muslim cap. He was accompanied by an entourage of aides and other government figures, including the chief of the local police.

James Watt and other protest leaders used a megaphone to recite their demands. They wanted the bupati to use his authority to push the companies to resolve land conflicts, and force them to provide a fifth of their land for community plantations. Darwan listened, and replied that he welcomed the arrival of the people and would try to convey their aspirations to the companies. But he said it would be impossible for companies to provide smallholdings from within their plantations as they were not legally required to do so. They shouted him down, yelling at him that he was a liar, as James remembers it. Darwan raised his hand to try to quiet them. They kept on shouting.

“It embarrassed him,” James said. “He decided he didn’t want to talk anymore, so he turned around, went inside and left out the back.”

The protest took place during a sharp escalation of conflicts over land across Indonesia. The following month, a murky conflict in Mesuji, southern Sumatra, became the centre of national attention after a retired general screened a video at a parliamentary hearing in Jakarta, purportedly showing evidence that the security guards of an oil palm company had beheaded farmers.

A few months later, hundreds of villagers occupied a port on Sumbawa island in defiance of a mining permit issued to an Australian firm. After five days, riot police opened fire on the blockade, killing two teenagers. The same month, 28 farmers from an island off the Sumatran coast sewed their mouths shut to protest a plantation license that covered more than a third of their island. By the years’ end, at least 22 people had died in hundreds of actions across the country.

The protest took place during a sharp escalation of conflicts over land across Indonesia.

Pundits chided protesters for “disregarding their democratic right of bringing grievances to their elected representatives” in favour of “street power,” as a Jakarta Post editorial put it. Budiardi, the local parliament member from Seruyan, saw it differently. “We tried to communicate with them about resolving the land conflicts and partnering with the people,” he told us. “But I think we can’t do anything if the bupati doesn’t care about what the people want.”

Budiardi at his home in Hanau, Seruyan.

That December, 11 people from Budiardi’s home subdistrict of Hanau entered a BEST Group plantation to commit their own act of vandalism. Fed up after years of petitioning the company, they used a truck and rope and ripped out several of its palm trees by the root. Everyone who participated was imprisoned for several months. Budiardi was not there, but he had organised protests in front of the company’s office, and was now labelled a “provocateur.” A warrant was issued for his arrest. Ignoring the summons, Budiardi travelled to Jakarta with a delegation of Hanau residents for a hearing at the national parliament. After a month or so as a “fugitive”, Budiardi too was arrested. He was tried and sentenced to four months in prison.

For Budiardi, it was the straw that broke the camel’s back. Upon completing his prison term and returning home, he emptied out his file cabinet, took copies of permits Darwan had issued and other documents behind his house, and set them on fire. “I lost my will to continue this struggle,” he told us. “I didn’t want to have anything more to do with it.”

If grappling with the plantations left Budiardi resigned to defeat, it only stiffened James Watt’s resolve. He would need it, for the frontrunner to replace Darwan after the end of his second and final term was none other than the bupati’s own son, Ahmad Ruswandi.

Ahmad Ruswandi on the campaign trail in Seruyan, March 2013.

By the time of the election in Seruyan, in April 2013, the post-Suharto era was buckling under the weight of local leaders who had honed the manipulation of democracy into a fine craft. Entire clans swept into the halls of government, as district chiefs sought to continue their reign beyond term limits, installing their spouses, siblings, cousins and children into political office. Later in 2013, the arrest of Indonesia’s top judge for taking bribes to settle election disputes would propel the issue of dynastic politics into the national spotlight. But when Ruswandi stood for bupati, it was already a pressing concern for those in Seruyan who could barely stomach the thought of another five years of rule by Darwan’s family.

“The way the people saw it, it was like changing the cover on your phone,” said Wardian, the farmer who had been jailed for stealing palm fruit in retaliation for the company grabbing his land. “Underneath, the machine is the same.”

Based on the usual rules of the game, Ruswandi looked like a shoo-in. Every one of the 12 parties with a seat in the local parliament had taken its place behind him. His main challenger had been forced out of the race when one of the parties withdrew its support and backed Ruswandi at the final hour. The head of its chapter in Seruyan expressed confusion at the decision, which had been made at the provincial level.

“The way the people saw it, it was like changing the cover on your phone. Underneath, the machine is the same.”

Ward Berenschot, one of the authors of Democracy for Sale, said that money routinely comes into play when candidates are seeking the backing of political parties, from which they need a measure of support in order to run. Parties can demand up to one billion rupiah, roughly equivalent to US$75,000, for each parliament seat they hold. Ambrin M Yusuf, the man who claimed he narrowly avoided being involved in the licensing scheme, was on Ruswandi’s campaign team. He told us that Darwan had stitched up the support for Ruswandi himself. “Haji Darwan took all the parties,” he said, using an honorific as a mark of respect. “It was bought and paid for at the province.”

Darwan was said to be so confident in his son’s chances that he boasted it would make no difference if an orangutan were his running mate. But as Ruswandi campaigned in the villages that had experienced his father’s form of development for a decade, he might have seen reason to take pause. Face to face with Wardian, he heard his path to victory might not be as clear as he anticipated. “You can’t rely on your money to win,” the embittered farmer warned him.

Darwan’s confidence proved to be misplaced. A grassroots movement swelled behind the only challenger, Sudarsono. Without the backing of a party, he had to stand as an independent, requiring him to collect thousands of signatures in order to run. Sudarsono was a member of the provincial parliament, while his candidate for vice bupati, Yulhaidir, had accompanied protesters in the massive 2011 demonstration as a member of Seruyan’s parliament. Key figures from the event, such as James Watt, backed the campaign and set up volunteer posts in their homes from which to organise.

James Watt at his home in Bangkal. The poster on the left is a relic of the 2013 election campaign.

The independents ran on a platform aimed squarely at the palm oil industry, signing a pledge that if elected, they would push the plantations to resolve land conflicts and provide smallholdings. It resonated with voters who felt betrayed by the man in whom they had once placed their faith. Sudarsono and Yulhaidir were announced the winners, taking 53.65 percent to Ruswandi’s 46.35 percent, and becoming the first candidates in Central Kalimantan to win a race for bupati as independents. Ruswandi accused the victors of cheating, but lost his appeal in the Constitutional Court.

Darwan was said to be so confident in his son’s chances that he boasted it would make no difference if an orangutan were his running mate.

The era of Darwan Ali was over. While the devastation his land deals had already triggered would continue, he had lost his power to do further damage. At least for the time being. – to be continued.

Photos by Leo Plunkett, Sandy Watt, Tom Johnson and Sam Lawson. All other illustrations by Sophie Standing.

This article was curated jointly by the environmental news website Mongabay and The Gecko Project, an investigative journalism initiative established by Earthsight. The article is part of an investigative series entitled Indonesia for Sale.

Recommended stories: