Malaysia and Singapore’s joint decision to set up stock market trading links between Bursa Malaysia (BM) and the Singapore Exchange (SGX) is likely to increase their capital markets liquidity while cutting down on cross-border trading costs in the long term.

The news was announced at the recent World Capital Markets Symposium in Kuala Lumpur, with Malaysia’s Prime Minister Najib Razak noting that both sides would benefit from “seamless access to each other’s markets with a combined market capitalisation of more than US$1.2 trillion and 1,600 public listed companies.”

According to reporting by the Business Times Singapore, the finer details of the arrangement are still being ironed out, but Securities Commission Malaysia and the Monetary Authority of Singapore will construct a supporting framework, including cross-border advisory and enforcement mechanisms.

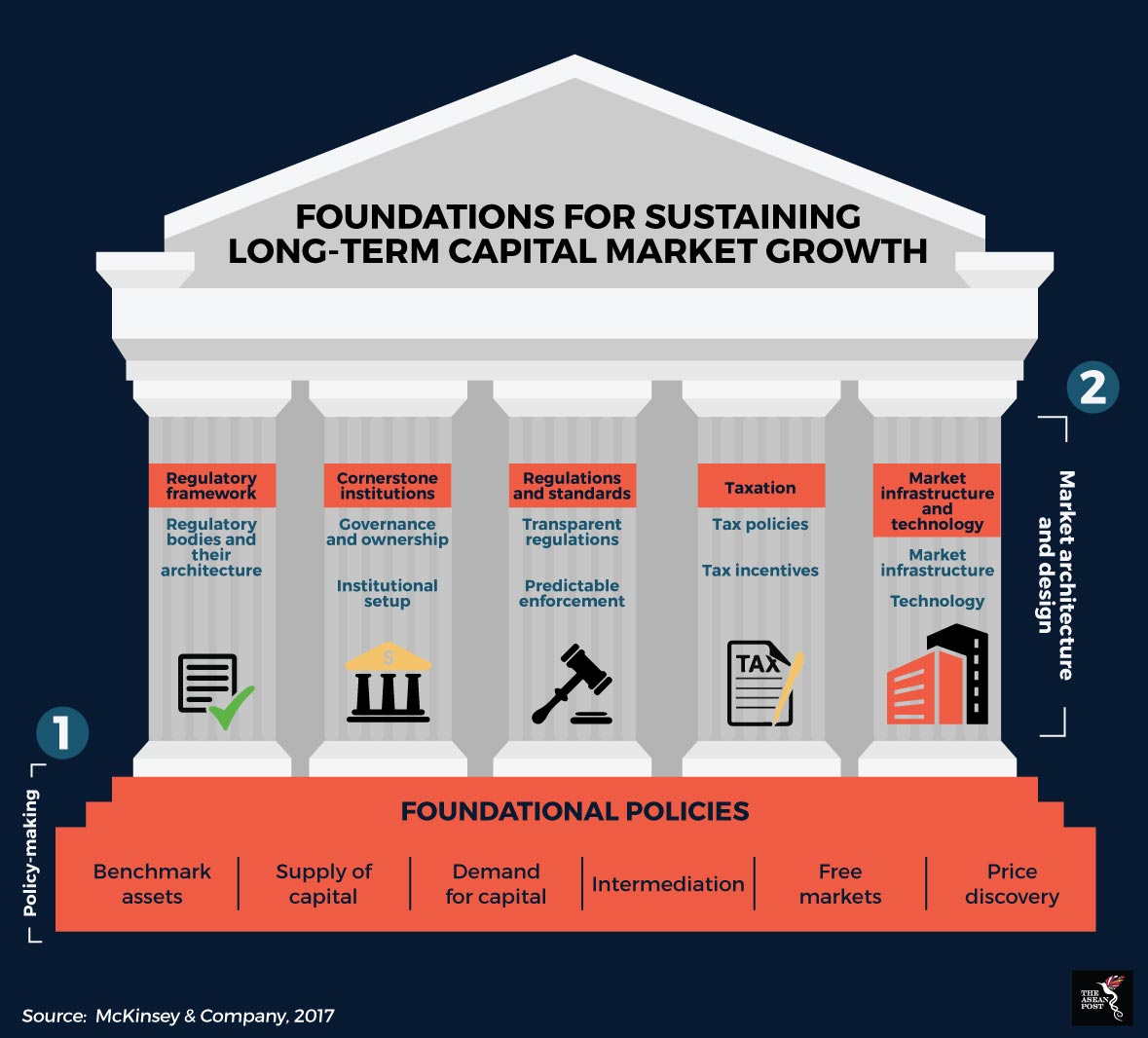

According to McKinsey & Company, the fundamental building blocks that would sustain long-term capital market growth include the existence of a regulatory framework, regulations and standards, cornerstone institutions, sound tax policy and the right market infrastructure and technology in place.

Establishing international stock trading links is one of the policy recommendations it highlighted in its 2017 report, ‘Deepening Capital Markets in Emerging Economies’.

In this way, the new ‘Malaysia-Singapore Connect’, as it has been dubbed, would both promote the setting up of a broad investor base, and encourage higher issuer participation.

This would result in a much larger supply of capital while at the same time raising demand for that capital, so long as capital supply and demand move at more or less equal rates in time.

According to the Financial Times lexicon, market liquidity refers to the extent to which there are sufficient numbers of buyers and sellers to ensure that prices remain stable during the trading process.

For the Malaysia-Singapore Connect, improving stock market liquidity also means that investors on both sides of the border would be able to trade equities without having to accommodate cross-border currency conversion costs.

Bursa Malaysia recorded a 71.1% increase in funds raised from new listings in 2017, according to financial results it released recently and has said that the new stock trading link with Singapore could mark a stepping stone towards establishing its proposition as a multinational marketplace within the ASEAN region. Yet according to analysts, Bursa Malaysia itself unlikely to experience significant benefit from the new stock trading link.

“Since the Asian crisis, I’m afraid most of the Singapore investors have sworn off Malaysian shares,” noted Pong Teng Siew, head of research at Inter-Pacific Research Sdn Bhd.

This was most likely a reference paid to the Central Limit Order Book (CLOB), a previous Malaysia-Singapore stock trading link that Malaysia’s government declared to be illegal in 1998, at the same time seizing the shares of 172,000 Singaporean investors in Malaysian companies.

Malaysian investors, on the other hand, would likely to be attracted to invest in SGX due to the strength of the Singapore dollar.

“They might be tempted to buy Singapore shares so that their wealth could be better preserved since it is denominated in the Singapore dollar, which is a more stable currency than the ringgit,” added Pong.

Singapore could also be attempting to replicate the success of the Hong Kong-China trading connect, which attracted US$1.025 trillion worth of trading in shares as of November 2017. The Hong Kong-China trading connect was set up 2014.

“Regional competition has put pressure on the exchanges,” said Song Seng Wun, an economist with CIMB Private Banking in Singapore. She was commenting on establishment of the new Singapore-Malaysia Connect.

“The two exchanges don’t want to be left behind and have investors flock elsewhere so now they’re waving a flag and saying, “we too have a trading link.”

A regional context

The success or otherwise of the Malaysia-Singapore Connect is also likely to be under the watchful eye of investors in the ASEAN region. A previous ASEAN trading link, established in 2012 introduced a new asset class to encourage investors to invest in ASEAN as a single market. To facilitate this framework, it also aimed to establish common clearing and settlements under the purview of Deutsch Bank.

Yet the ASEAN stock trading link was quietly shut down in 2017 after only three stock exchanges, namely those of Malaysia, Singapore and Thailand, became trading partners. The hesitancy on the part of the other countries could be due to concerns that they would not be able to compete on a level playing field. Any new listings were likely to be centred around the more established and liquid exchanges such as Singapore’s, which would snuff out any competitive edge held by the other ASEAN stock markets, according to analysis by Hiromi Hayashi, a financial industry analyst with the Nomura Institute of Capital Markets. Hence ASEAN countries with less developed capital markets would be likely to concentrate on developing their own capital markets first.

As of 2017, there were only four companies listed in the Yangon Stock Exchange in Myanmar as well as the Cambodia Securities Exchange, while the Lao Securities Exchange had five companies, according to reporting by the Nikkei Asian Review.

It is perhaps prudent that Malaysia and Singapore have set up bilateral stock trading links before attempting a resurrection of regional stock trading links between ASEAN countries, as ASEAN may not be ready for it. If the Malaysia-Singapore Connect is successful, however, it will pose as a banner of success for the remaining ASEAN countries to consider bilateral and even multilateral stock trading links in the future.

Recommended stories: