In the 21st century, data is a perennial need for the sustenance of our digital industries. The internet would not have become what it is today if not for data. Hence, for our continued development in the field of technology, the need for data will never diminish. Moreover, as the world becomes more global and henceforth, borderless, data will have to be mobile, able to travel across the tangible boundaries of nation states.

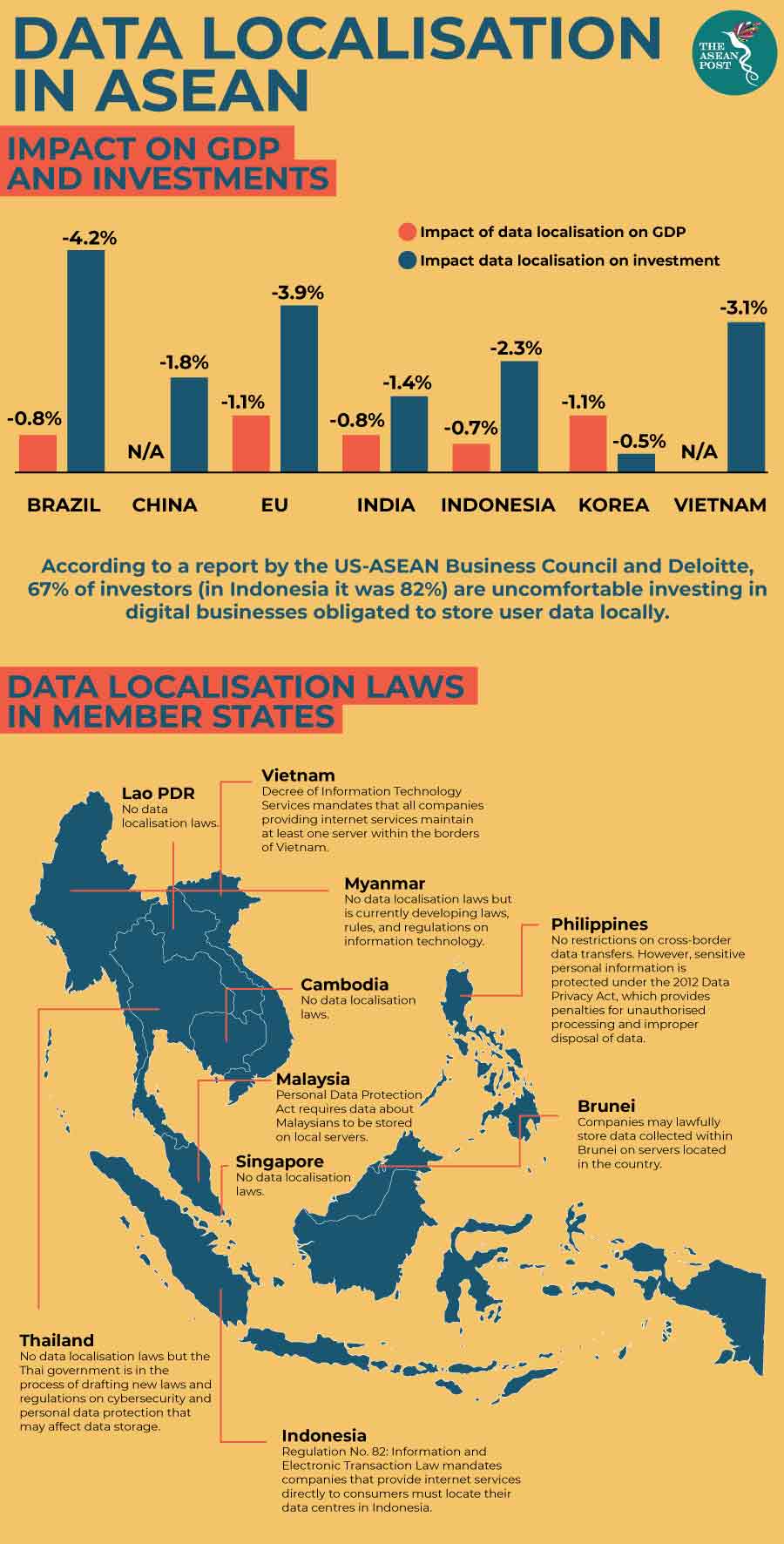

However, some states have chosen to erect digital barriers that prohibit the flow of data across borders. Data localisation laws – as they are generally referred to – are laws enacted to ensure data obtained within a country is stored, processed and used locally only and cannot be transferred to another country.

There are, as always, two sides to this argument. Supporters of data localisation laws say that such enactments are vital to protect the privacy of the citizenry of the country. Such arguments are also often rooted in the principle of national sovereignty as a breach of citizen’s data could constitute a threat to national security.

Among member states of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), four countries, namely Malaysia, Brunei, Indonesia and Vietnam have data localisation laws. Countries like Thailand and the Philippines have separate data privacy legislation which aren’t explicit about data localisation but a broader reading of such laws could see possible application to data localisation.

On the other hand, countries like Singapore lie on the opposite end of the spectrum. Instead of pursuing data localisation, the island republic takes a focused approach towards promoting its digital economy and creating a sustainable digital ecosystem which allows for data-reliant industries to thrive across varying sectors.

The argument against data localisation laws is an economic and market driven one. Barriers towards exchange of data could possibly harm economic welfare in a similar manner that tariff and non-tariff measures have on the free flow of goods and services. As ASEAN, under Singapore’s chairmanship this year aims to strengthen the regional digital economy, data localisation legislation could hamper such efforts.

Requirements to localise data could limit access to digital commerce networks for businesses and consumers alike which would then constrict access to online resources and opportunities. Besides that, it would impose limits on big businesses aiming to synthesise large data sets which would deprive local businesses of the ability to improve their products at a lower cost. Moreover, data localisation would in essence, create multiple entry point global platforms which would then see threats of cyber-attacks increase.

Nevertheless, the concerns surrounding data privacy are not to be understated. If anything, the Cambridge Analytica scandal only stands to validate our fears that such amassed data could be put to use in nefarious ways. One way to negate such concerns is to think regional.

Keeping the ASEAN Way of conducting affairs in mind, member states should strive to develop national privacy laws that address the concerns at hand. Then, such laws can be harmonised at a regional level, effectively creating an ASEAN-wide regulatory framework which would allow data to flow freely but with the necessary checks and balances in place to ensure no exploitation takes place.

Malaysia passed privacy laws in 2010. The Philippines and Singapore followed suit in 2012. Indonesia and Vietnam have broad overarching legislation in place which could use some narrowing down. Thailand is currently in the midst of developing laws on cybersecurity and personal data protection. Looking at Malaysia, Singapore and the Philippines, Brunei has taken heed to discussions pertaining to privacy legislation. Cambodia, Lao PDR and Myanmar are the three states that lag behind the others and should catch up with legislation of their own based on the experiences of their neighbours.

ASEAN could emulate the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) Cross Border Privacy Rules (CBPR) which is a system that requires participating businesses to develop and implement data privacy policies in line with the APEC Privacy Framework. These policies are monitored and assessed by independent accountability agents, consistent with previously agreed upon standards and practices and are enforceable by law.

In facing 21st century challenges, we will always be open to malicious attacks which could lead us down the path of trepidation. But that should never be allowed to hamper our progress in this digital age which is increasingly reliant on data analytics. The trick is to find a middle ground so that we may proceed to change the world, knowing fully well that we have laws to protect us against those who exploit cross border data flows.