Financial centres across the globe are often named after the specific location they are constructed on. This can be seen with the Marina Bay Financial Centre in Singapore, the Hong Kong International Finance Centre, and Wall Street in New York City, amongst others.

In Malaysia, however, this is not the case. Deemed to be a symbol of renewed economic hope for Malaysia when originally envisioned under the 10th Malaysia Plan which was introduced in 2010, the Tun Razak Exchange (TRX) takes its name from ousted Prime Minister Najib Razak’s beloved father, Abdul Razak Hussein.

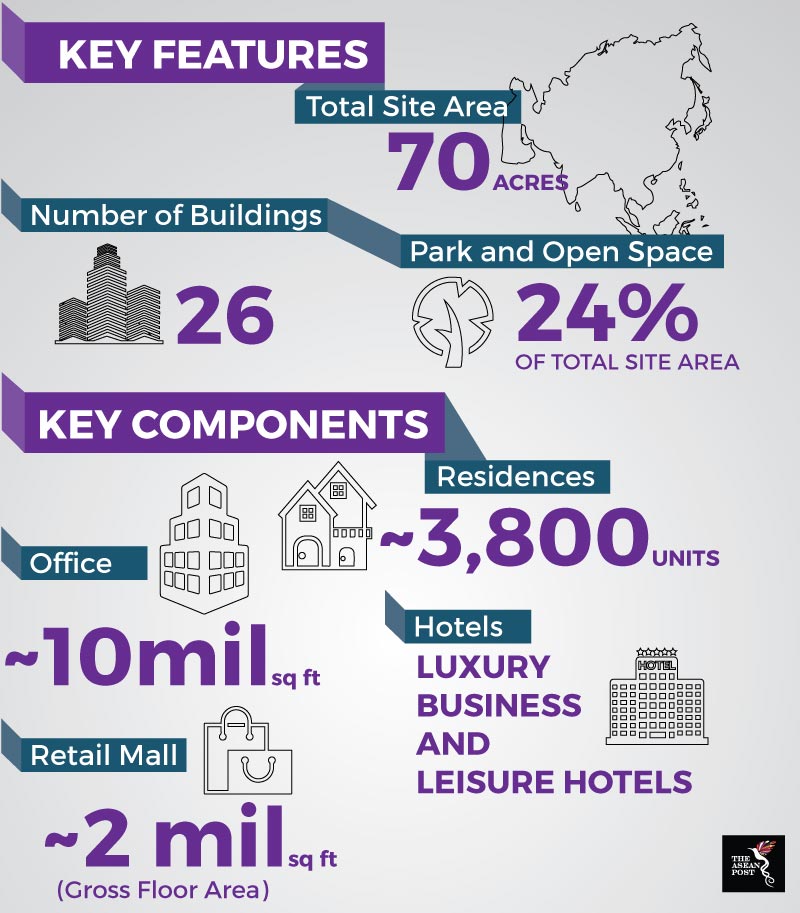

At the heart of TRX is The Exchange 106, one of the newest skyscrapers to grace the Kuala Lumpur skyline. After a mere 19 months of construction, the tower has already reached a height of 450m, with a projected height of 492m upon completion, overshadowing the Petronas Twin Towers, which have become an iconic part of Malaysia’s identity.

It has been alleged that Indonesian developer Mulia Group had purchased the landmark site at a discounted price but has regardless accelerated its construction via the use of tower cranes and concrete pumps. Construction is proceeding at the speed of one completed storey every three days, with 2,000 workers across 22-hour shifts. Exemplary by international standards.

Source: TRX.my

Another development component, the lifestyle quarter, was recently reported to be facing funding issues by a leading Malaysian financial daily, mainly due to a weak Malaysian property market, prior links to 1MDB and the recent change of government.

Given its prominence as a soon to be regional financial centre, as well as a national landmark, many have questioned whether the megaproject could adopt a more inclusive name to reflect its status.

Financial hubs

At its most basic, a financial centre is a location with an agglomeration of players in asset management, banking, financial markets, and insurance, among others. Moreover, financial centres usually host companies that offer a wide range of financial and legal advisory services, pertaining to, for example, large-scale mergers and acquisitions and initial public offerings which have direct economic impacts.

The development of TRX as a financial centre capitalises on economic forecasts placing Asia as a key player in global trade over the next 20 years.

“Malaysia, home to one of the most robust and thriving economies in Asia, is responding to this shift in global economic power by building a knowledge-based, high-technology economy, implementing liberalisation measures, and paving the way for superior investment opportunities,” said former premier Najib Razak at the official launch of TRX on 30 July 2012.

Najib Razak went on to explain that 500,000 jobs would be created directly and indirectly by the scheduled completion of TRX in 2027, along with the relocation of 250 of the world’s leading companies to the mixed development. However, current developments surrounding TRX may suggest otherwise.

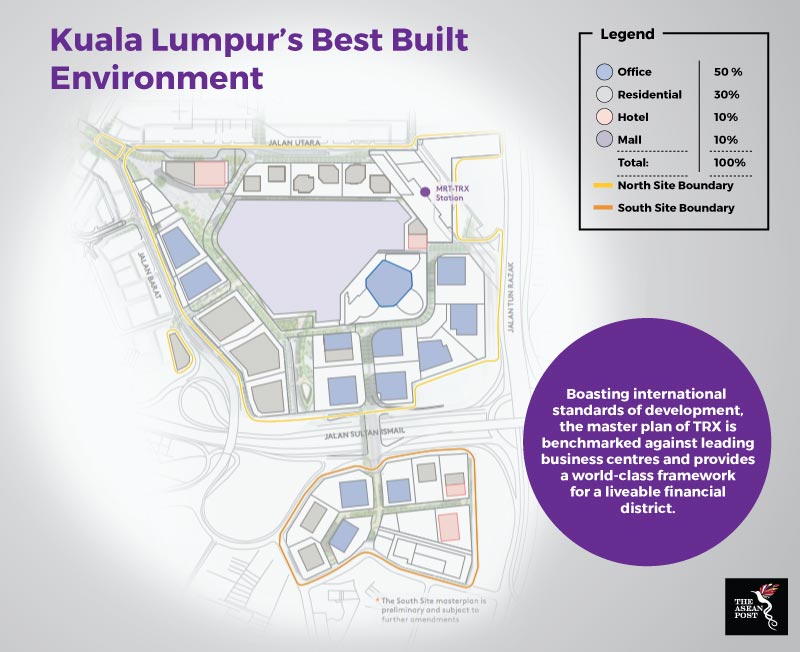

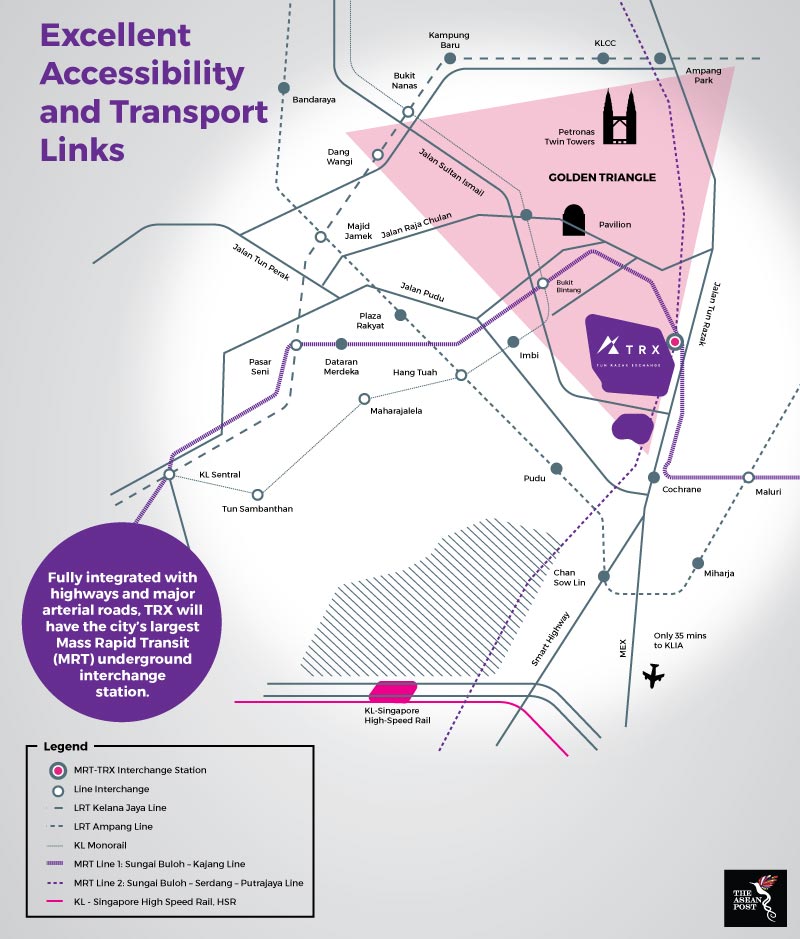

Envisioned under the 10th Malaysia Plan as the Kuala Lumpur International Financial District (KLIFD) prior to its “subtle” 2012 rebranding, the 70-acre TRX development in Kuala Lumpur, was designed with the potential of becoming a leading centre for international finance and business. As a seamlessly connected district in the heart of Kuala Lumpur, TRX features an integrated MRT interchange station, and is further supported by direct links to Jalan Tun Razak, the Maju Expressway, and the SMART Tunnel, three major routes in and around the city centre.

Source: TRX.my

With an estimated gross development value (GDV) of US$10.1 billion, TRX is deemed a natural expansion of the Golden Triangle, Kuala Lumpur’s prominent commercial, shopping, and entertainment hub.

In line with its global aspirations, TRX is believed to be modelled after international global financial centres such as Canary Wharf in London.

The financial offices of banks, including JPMorgan Chase, Citi, HSBC, and other institutions in the financial district of Canary Wharf, are pictured from Greenwich Park in London on October 21, 2017. (AFP Photo/Tolga Akmen)

However, all this serves to underscore the question of why it derives its name from a personality, instead of its location.

Kuala Lumpur International Financial District

Over the years, Malaysia has been entangled in a barrage of international allegations linked to an alleged multi-billion dollar money laundering scheme. That aside, the Malaysian economy is bracing itself as it looks to revamp its tax revenue system via the abolishment of the much-maligned goods and services tax (GST) coupled with a depreciating ringgit, against a positive backdrop of rising crude prices and less leakages (as promised by the new government’s reform agenda).

As a balancing act, reassessing the role and strategic importance of TRX to the Malaysian economy is vital. A possible rebranding and repackaging could attract substantial foreign direct investment as the new government, led by the Alliance of Hope (Pakatan Harapan), looks to re-establish Malaysia on the international circuit. However, the task of convincing fund managers and institutional investors may prove challenging given the current climate in Malaysia.

The need to reinvigorate Malaysian capital markets with a breath of fresh air by way of liberalising the economy and opening it up to international investment banks and fund managers is paramount. This bold effort could prove to be the catalyst to relaunch the KLIFD, thus allowing the development of a new regional financial hub, increased deal flow and better knowledge transfer on a much-handicapped Malaysian professional sector.

In the long run, the KLIFD would increase overall competitiveness among regional financial hubs and attract high quality foreign talent which would help in bridging the knowledge and skill gap in Malaysia.

While naming a specific location or building after a prominent national figure is not uncommon (with New York’s John F Kennedy airport or the Rockefeller Centre as examples), many have contended that in TRX’s case, it would be wiser to leverage on Kuala Lumpur’s reputation as a vibrant multicultural capital and gastronomic paradise.

Source: TRX.my

It is worth noting that the ideal behind this observation is not to disparage Tun Razak as a visionary whose work uplifted Malaysia’s ethnic Malay community through initiatives such as the establishment of the Federal Land Development Authority (FELDA). Rather, is the desire to move away from a penchant for naming buildings and landmarks after forefathers, particularly institutions such as financial centres, which are typically held to nonpartisan standards given their core business.

Visionaries such as Lee Kuan Yew and Mahathir Mohamad have chosen not to name any institutions after themselves or their families. By maintaining TRX’s naming convention based on a historic figure, the country could be losing a brilliant opportunity to recalibrate and reposition itself on the international capital market.

Here, Malaysia can draw a parallel with their Singaporean counterparts, in that previous leaders of the neighbouring island republic avoided naming institutions after eminent figures in the country’s history as a rule. The Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy was, in many respects, the first modern-day exception to this rule, though perhaps it is understandable in light of the fact that the institute is not linked to financial inflows from international entities, as is the case with financial centres across the globe.

People sit along the promenade of Marina Bay overlooking the Singapore's financial district on November 1, 2012. (AFP Photo/Roslan Rahman)

Way forward

The creation of a new Malaysia – #MalaysiaBaru according to the local millennial cohort – is of utmost importance, representing a growing pride that its citizens have in its architecture and landmarks, as well as its economic and social progress. Many of the young voters feel they now have a voice and want to contribute to economic development and social progress. Leveraging on this wave, TRX could be rebranded to reflect the ideal of a more inclusive Malaysia where dynastic thinking is substituted with a more global and universal outlook by the body politic.

For the first time in Malaysia’s 61-year history, its citizens feel truly Malaysian. Sentiment on the ground, according to sources, is that, for the first time since the nation’s independence, this transition represents the perfect chance to catapult Malaysia to its rightful position on the global stage following years of lost opportunity, and its re-emergence as an Asian Tiger.

Many millennials also feel there is a need to do away with outmoded thinking so as to build a citizenry with long-term perspectives and a universal outlook. In this light, reverting TRX to the Kuala Lumpur International Financial District as initiated under the 10th Malaysia Plan, could present Malaysia with the golden opportunity to reintroduce itself on the global stage. A reintroduction built on how London takes prominence over the United Kingdom in the mind of business travellers and tourists. Such a strategic shift with the right financial liberalisation mechanisms, could propel the refreshed financial hub as a bona fide regional financial centre.

Furthermore, in order to untangle and distance itself from the allegations of mass corruption and embezzlement, this need to reinvent TRX would represent the ideal solution to Malaysia’s loss of political and financial integrity globally, and its commitment beyond political underpinnings. Ultimately, this would represent a beacon of hope for generations to come.