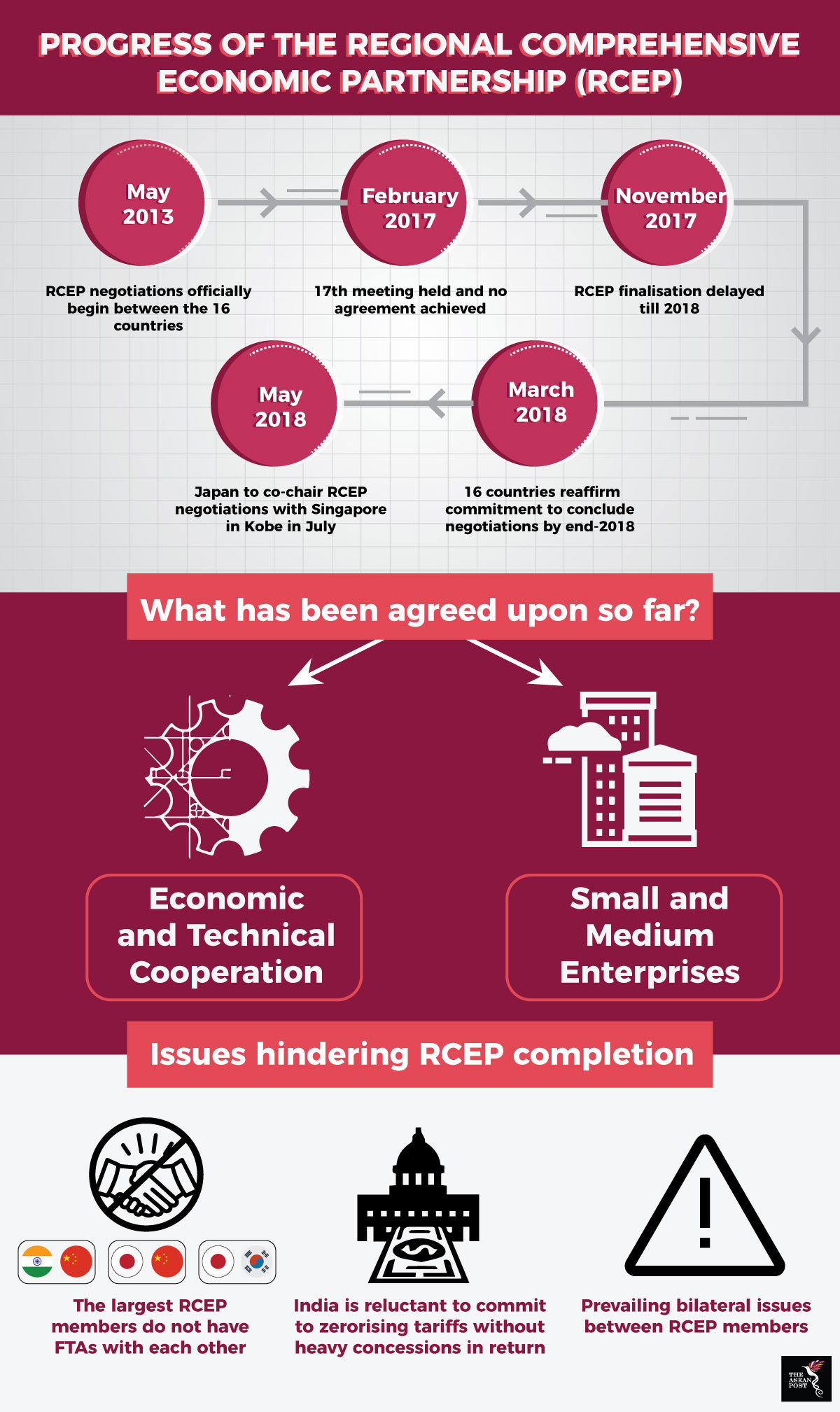

The Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) inched closer to completion last March when the ministers of all 16 countries met in Singapore for their fourth intersessional meeting. Next up on the almanac for leaders is a ministerial meeting which will be held in Tokyo on 1 July.

Participating economies in RCEP include all 10 members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), Japan, South Korea, China, India, New Zealand and Australia. The mega deal covers trade in goods and services, investment, economic and technical cooperation, intellectual property, competition, dispute settlement and e-commerce.

Thus far, one chapter on Economic and Technical Cooperation and another on Small and Medium Enterprises have been concluded. Still, there is plenty left for the 16 members to hash out in the upcoming meeting in a month’s time.

High up on the order of priorities is tariffs. India, which represents almost 10 percent of the combined Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of RCEP economies has long been dragging its feet on the issue of tariffs. India is currently being pressured to free tariff lines on 92 percent of items for all RCEP members including China but has countered that with 80 percent of all tariff lines with a 6 percent deviation either way.

Analysts have long expected India to agree on stiffer tariff regulations only if it receives heavy concessions for its services exports in return. Sanchita Basu Das, Lead Researcher of Economic Affairs at the Singapore based Yusof Ishak Institute told The ASEAN Post that New Delhi has also been pushing for greater services sector liberalisation especially in professional labour mobility.

“India wants to provide a tiered tariff structure – for ASEAN, China and the rest. As RCEP is a comprehensive agreement, it also wants to negotiate for movement of professional in lieu of giving market access. This is a sticky issue and is prolonging the discussion.” she said in an email reply.

According to Das, ultimately, India cannot afford to dawdle on the matter as it will risk losing out on other economic benefits accompanying the RCEP.

“There is a good chance that India will compromise further as otherwise it may lose participating from the economic leg of a mega-Asia trading architecture,” she further opined.

Source: Various sources

On top of that, prevailing geopolitical tensions between member economies may lead to the continued stifling of progress with regard to RCEP negotiations. China’s inroads into Pakistan as part of it ambitious Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has intensified tensions between the two. Besides that, the South China Sea dispute between China and five other ASEAN members could throw a spanner in the works along the way.

Nevertheless, nations have a tendency to put such issues on the backburner in the promise of greater economic prosperity. Moreover, participating RCEP economies have a point to prove against the current worrying trend of economic protectionism threats of a US-China trade war, and an overall global political mood against free trade. Most of the 16 countries are emerging economies that cannot afford to be left out of the international trade order or risk reversing substantial economic gains garnered thus far.

This time out, the RCEP can also stand to leverage on Singapore’s determined leadership for a conclusion of the trade deal. As chair of ASEAN for 2018, the island nation has included the completion of a high quality RCEP in its list of chairmanship priorities.

As a nation reliant on international trade to flourish, Singapore is in a better position to take the lead on matters. RCEP is often conflated as a Chinese-led initiative but is in fact an ASEAN-led one. It is better understood as an integration of the ASEAN+1 FTAs in order to negate a noodle bowl of conflicting bilateral FTAs in Asia.

Against protectionist undertones and US rescindment of the Trans Pacific Partnership (TPP), RCEP stands as the alternative for ASEAN members which seek to advance the trade liberalisation agenda. As one of the most dynamic regions in the world, Southeast Asia does stand to benefit from such an endeavour in the long run. But whether or not it can stick to its end-2018 deadline will be more apparent come July.