At 17 years, Indonesia’s voting age is the lowest in the Southeast Asian region and is one of the lowest in the world. However, 25-year-old Agnes Anya, a resident of Indonesia’s bustling capital, Jakarta, believes that most youths in her country feel disengaged from Indonesian politics and are only recently getting interested because they view it as being trendy.

“Most politicians or political essential roles are held by the older generation. From what I see, youths are sceptical about parliamentarians and political parties in general,” she said.

Voter apathy has been a longstanding issue amongst Indonesian youths. According to data sourced from the Indonesian elections commission, the previous 2014 general elections saw less than half of voters aged between 17 and 29 years casting their votes. In comparison, more than 90 percent of those aged above 30 voted.

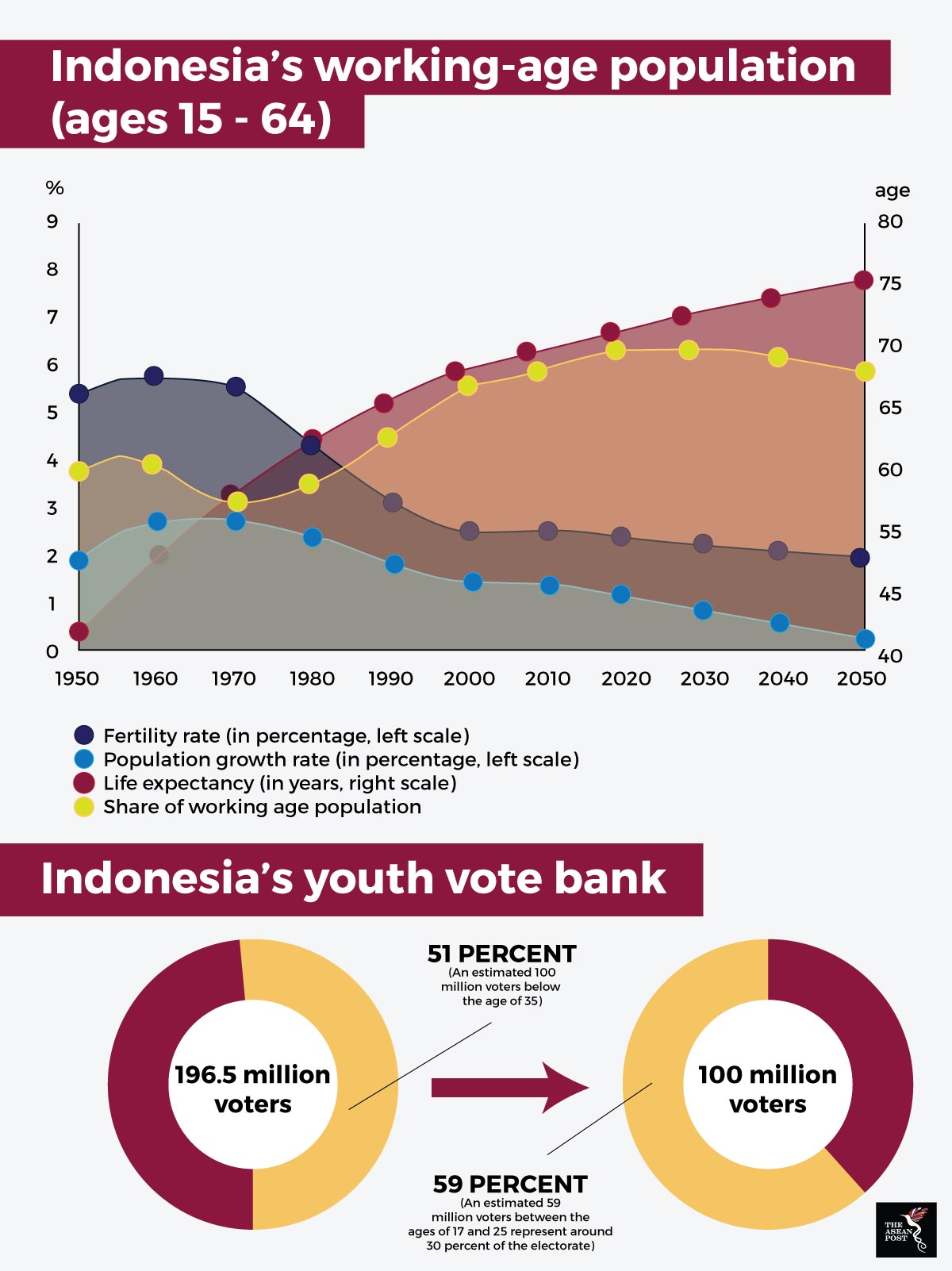

However, the youth vote bank is an incredibly critical segment of Indonesia’s electoral demography. In 2004, those aged between 17 and 24 accounted for only 18 percent of the electoral roll. Now, that number has ballooned to 30 percent. Some estimates suggest that by 2019, there would be approximately 100 million voters below the age of 35, making up more than half of the 196.5 million strong electorate in Southeast Asia’s largest democracy.

In search of the new guard

With elections looming, millennials are becoming the prime demography for political parties to pander to. Indonesian politics is starved of fresh faces and voices which has been the main reason for the scepticism among the youth towards politics in their country.

Enter, Partai Solidaritas Indonesia (PSI) – or Indonesian Solidarity Party – founded in 2013 by a 35-year-old journalist on a progressive platform. This relatively new player in Indonesian politics boasts 400,000 members – two thirds of whom are below the age of 35. Besides imposing a maximum age restriction of 45 for registration, it also strives to maintain a 30 percent female membership.

According to Deasy Simandjuntak, a visiting Indonesian researcher at the Singapore based ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute, PSI’s platform of anti-intolerance and anti-corruption could be a strong pull factor for younger voters. However, she also expressed her apprehensions towards the sway that PSI may hold on the millennial voter bank.

“For some, PSI has an image that seems to be “elitist” and “urban”. This could be unattractive to rural voters or those from a middle-lower class background,” she said. “Almost every party has a youth wing or specific section focusing on appealing to young voters, thus PSI is not the only one with this strategy.”

Another problem that PSI may run into is that it lacks traction in a demography which places importance on a party’s track record as well. A recent survey indicated that only 10 percent of voters are aware of PSI. The party’s inexperience has been a stumbling block in its path towards gaining legitimacy amongst Indonesian youth.

Source: Various sources

Nevertheless, Simandjuntak remarked that, “PSI could still attract more voters if they can be more inclusive in their approach without sacrificing their platform.”

Anya, who has been following PSI’s campaign opined that much of their young cadres are not articulate enough as politicians and tend to be populists only.

“I saw a campaign video of PSI featuring one of its popular politicians. The video highlighted corruption by the House of Representatives' former chief. She then started to make arguments that, in my opinion, were not new and enlightening,” she said. “It was just provoking and blunt.”

A cure for apathy

Incumbent Indonesian President, Joko Widodo – commonly referred to as Jokowi – will likely be facing off with his former opponent, Prabowo Subianto in a repeat of the 2014 Presidential elections. Although these elections are slated for 2019, the campaign trail has already kickstarted, with Jokowi already in the lead.

Figures by Jakarta-based pollster Charta Politika indicate that Jokowi is performing well in the island of Java where 56 percent of the electorate reside. According to the survey, except for Banten, Jokowi leads comfortably over Subianto elsewhere on the island.

With the strong possibility of a repeat of 2014, voter lethargy – especially amongst the youth – may translate to lower voter turnout numbers. Nevertheless, Simandjuntak is inclined to believe the opposite.

“There are concerns about young voters’ political apathy, as half of them did not turn out to vote in the 2014 election. However, the political developments since 2015, for example the rise of sectarian politics which have led to deeper factionalism in Indonesia, would likely increase the voter turnout in 2019,” she said.

“The increasingly high internet usage among young people also means that young voters have better access to information and are likely to be more politically aware,” she added.

Xenophobic sentiments and sectarianism would likely dominate these elections although it may mostly be used to gain political mileage or used as a political tripwire to attack opposing candidates. With the 2019 elections less than a year away, Indonesia’s future rests on the shoulders of its youth. The question remains; will they mobilise and vote to bring about change or will they stay away and remain indifferent?