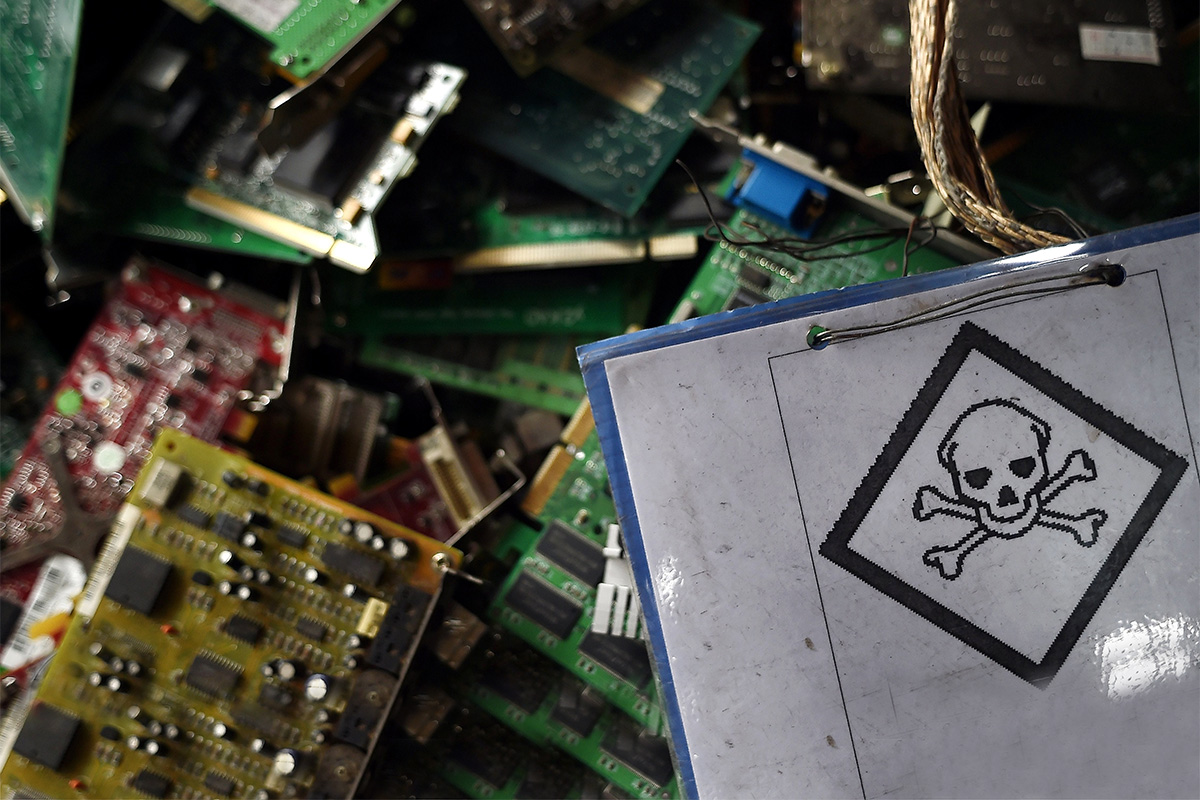

A police raid on the Wai Mei Dat Thai Recycling factory, 100km east of Bangkok last month revealed a shocking find. The 40-acre complex was laden with huge piles of electronic waste – keyboards, motherboards, electrical wires, computer screens and smartphone batteries, just to name a few.

The high-level operation found that undocumented immigrant workers from Lao PDR and Myanmar were used to recycle or discard the e-waste at the site. Some of the electrical and electronic equipment (EEE) would then be further treated to extract precious metals including gold, silver, palladium and platinum. The workers were reportedly untrained and were often times exposed to toxic shredder dust as well as toxic fumes from hand cooking electronic circuit boards.

Wai Mei Dat is a large Chinese company with facilities in the United States (US), Lao PDR and Thailand and offices in Hong Kong. Although the company is a registered member of the Institute for Scrap Recycling Industries (ISRI) and also a R2 certified (Responsible Recycling) company in Hong Kong, it was eventually charged with illegal importation of dangerous waste.

The scourge of e-waste flowing into Thailand and other Southeast Asian nations is a direct impact of China’s dramatic decision to block waste imports in 2018. Over the past two decades, China was considered the primary dumping ground for e-waste in the world. Now that it has closed down its facilities and severely cracked down on all forms of waste imports, companies like Wai Mei Dat have moved their operations to countries in Southeast Asia due to lax environmental regulations there.

However, e-waste imports into Southeast Asian states have seen an upward trend recently and the accumulation of these wastes has now become unmanageable. Thailand is a major destination for such e-waste which has prompted fears of the long term detrimental effects on the environment there. In the first five months of the year, it is estimated that 37,000 tonnes of e-waste entered the country with more believed to have come in illegally. Thai authorities are now beefing up efforts to block further e-waste imports by conducting thorough inspections of the over 2,000 recycling factories in the country.

Seeking a global solution

The resulting impact of China’s policy to ban waste imports points to a greater problem within the broader structure of e-waste disposal on a global scale. For a long time, China has been the go to place for e-waste disposal, receiving close to 70 percent of the world’s e-waste. However, the country cannot be faulted for its recent policy change which acknowledges that the long-term environmental and health hazards far outweigh the short-term monetary gain from e-waste imports.

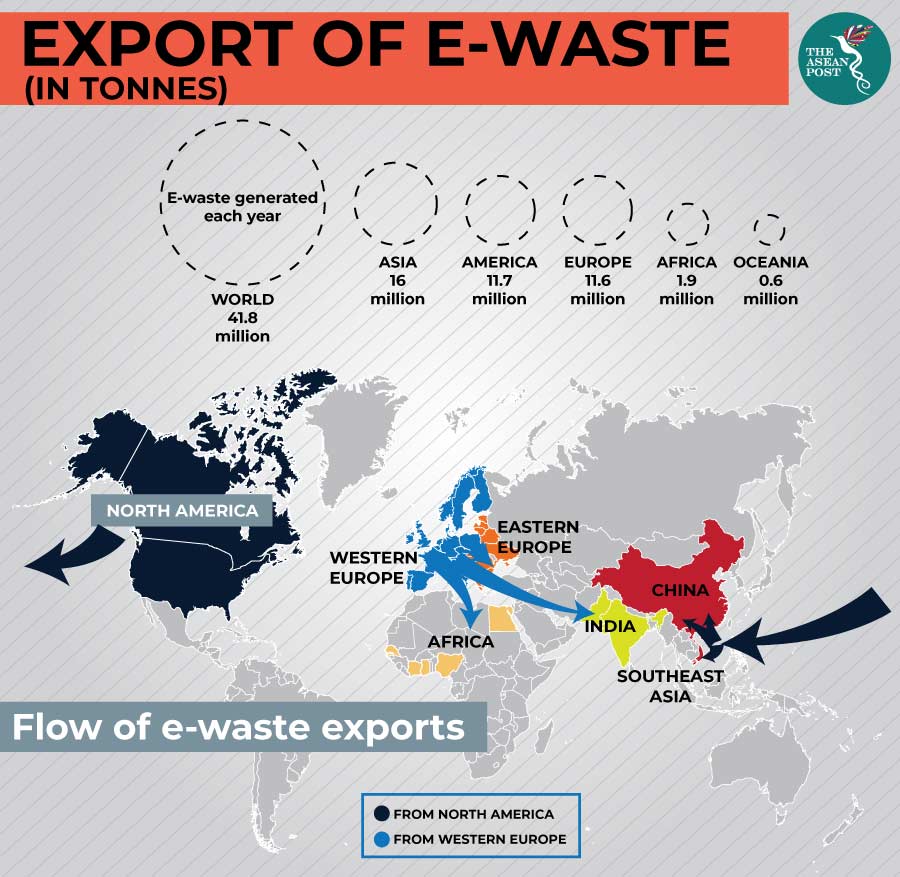

Meanwhile countries like the US and Canada together with European nations continue to produce voluminous amounts of e-waste. Europe and the US alone contribute to almost half of the total e-waste generated annually. On top of that, these countries show little willingness to develop the necessary infrastructure to deal with it domestically, preferring instead to export their e-waste to lesser developed countries.

US based environmental watchdog, Basel Action Network (BAN) has employed GPS devices to track the flow of e-waste from the US, Canada and Europe and revealed that 40 percent of e-waste was exported to Asia. The trackers also show that the waste arrives in Hong Kong before making its way to final destinations like Thailand and Pakistan, often following the “path of least legal resistance.” Accordingly, BAN has called for other Asian countries to emulate China and bar the import of waste.

“It is vital that all Asian countries likewise slam their doors shut to a free-trade in hazardous wastes to protect their territory,” said Jim Puckett, Director of BAN.

The organisation which has been tracking waste flows for two decades called on Asian countries to ratify the Basel Ban Amendment or risk facing a “tidal wave of electronic and plastic waste”. The amendment which would alter the existing Basel Convention and make it illegal to export hazardous e-waste for any reason from developed to developing countries. The Basel Convention was adopted in 1989 to tackle transboundary movements of hazardous waste and their disposal.

“Every country in the Asian region should ratify the Ban Amendment and implement the ban into national law as a matter of urgency," Puckett said. “This action will not only protect their own countries from the unsustainable waste trade tsunami, but will help the entire world as well, as it will ensure that the Amendment enters into the force of international law.”

By adopting a global solution to a transboundary issue, countries within the region are better predisposed to put an end to e-waste imports that can prove detrimental to them in the long run. Southeast Asian states must take a united stand and not be pressured into accepting more e-waste into their countries.