China has been the world's largest importer of recyclable materials since the 1980s. In 2017, China's Ministry of Ecology and Environment announced an import ban of 24 types of solid waste (later updated to 32 types) including unsorted wastepaper, textiles and plastics. The secondary raw material harvested from the imported waste is expected to be replaced by domestic resources. The import ban is to be implemented in two tiers, with the first 16 types of waste banned by the end of 2018, and the remaining types banned by 2020. On 29 June, China limited the entry points for imported waste into the country to 18 designated river and sea ports, effective 1 January, 2019.

Import and export of hazardous/scheduled and other wastes for final disposal as well as for recycling and reuse are regulated under the Basel Convention on the Control of Transboundary Movements of Hazardous Wastes and their Disposal. The international treaty also promotes environmentally sound management of waste, particularly for developing countries and countries with economies in transition.

E-waste is categorised as hazardous by the Basel Convention due to the presence of toxic materials such as mercury, lead and brominated flame retardants. E-waste may also contain precious metals such as gold, copper and nickel, as well as rare materials of strategic value such as indium and palladium. These components could be recovered, recycled, and used as a valuable source of secondary raw materials. According to the Basel Convention website, it has been documented that e-waste shipped to developing countries is often not managed in an environmentally sound manner, posing serious threats to both, human health and the environment.

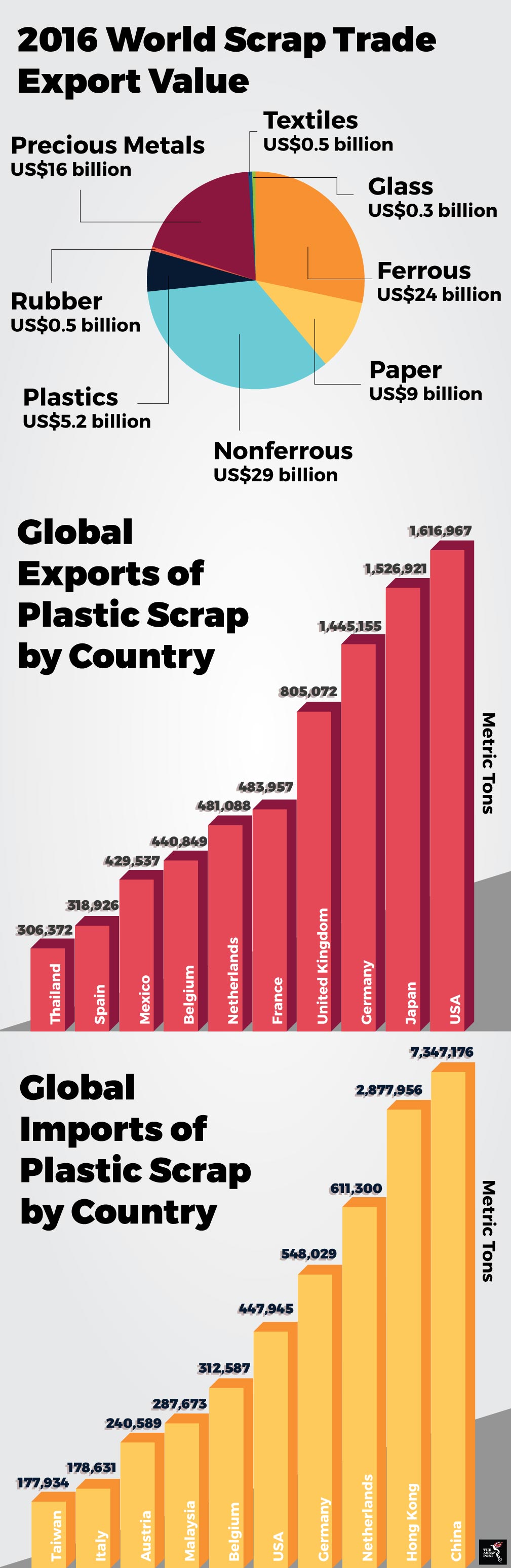

Source: Institute of Scrap Recycling Industries, Inc.

Regional impact

The import ban on scrap waste by China to reduce environmental impacts there has forced waste exporters, mostly from Europe and North America, to look for alternative destinations. As a result of the ban, many of these shipments have now found their way to ports in Southeast Asia. The sheer number of vessels carrying waste have begun to clog the already overburdened ports in the region. This in turn has resulted in some Southeast Asian governments imposing similar waste import bans as local port and Customs and Environmental officers scramble to deal with the worsening situation.

Thailand and Vietnam have both declared similar import bans in June due to the additional tonnage of waste they have had to handle. The situation there has been made worse by reported findings of prohibited hazardous electronic waste (e-waste) mixed in with the recyclable waste. While Malaysia is still accepting scrap shipments, market players in the country are worried that similar disruptions will occur soon.

Following the ban by Thailand’s government, more than 30,000 containers carrying the diverted waste shipments from China are now sitting idle in Thai ports. Similarly, suspension of unloading services and 9,000 idle containers have also been reported in Vietnam, including at the Cat Lai port that is notorious for its capacity issues.

According to the Bureau of International Recycling, it is generally accepted by industry experts that the sheer tonnage of displaced waste imports that have been diverted from China cannot be absorbed by facilities in other destinations. The large amount of waste imports will saturate the market, and impact local operations and inflate prices. A combination of immediate and long-term solutions is needed to ensure the smooth operation of these overburdened ASEAN ports. This includes identifying alternative downstream destinations and building handling capacity for the waste stockpile within the exporters’ national boundaries.

The Thai waste import ban comes on the heels of the country’s Customs operations to identify and seize prohibited waste that was wrongly declared as recyclable waste. Police raids were also carried out on existing waste operators who do not have the capability nor the facility to handle the imported waste. This is not the first time Thailand has introduced a scrap import ban. The current Thai ban is preceded by previous import disruptions and reversed shorter-term bans in recent months that has caused waste loads to be backed up resulting in a temporary halt to new bookings for waste shipments.

The executive president of the China Scrap Plastic Association (CSPA), Steve Wong, was quoted by regional news agencies as saying that thousands of containers have failed to be cleared by consignees for months, with the very slim likelihood that the affected containers will be moved on from the port. As a result of this, demurrage charges are also growing daily.

“The massive flow of plastic scrap shipments to these countries after the market shift from China has far exceeded the permitted import volumes and the operation capacities of their main ports,” he explained.

Wong said, in response to the China ban, many recyclers had shifted their consignments to India and several ASEAN countries, namely Malaysia, Vietnam and Thailand. However, they now face difficulties in getting approval permits due to the clamp down operations by the governments in these countries. Non-compliance with existing environmental regulations has also made the process more difficult.

Plastic recycling experts have noted that Indonesia may be a friendlier destination as other potential plastic waste recycling destinations such as Taiwan and the Philippines were unable to take on additional volumes.

The waste is not going away. China’s unwillingness to continue playing wastebasket to the rest of world underlines the country’s nascent commitment to its environmental ideals. As China continues with its National Sword policy, the world should brace itself for more changes that will send shockwaves across various industries. The clogged Southeast Asian ports and growing waste stockpile should be strong enough impetus for the prudent use of resources while managing waste effectively at the source.