In Southeast Asia of late, the spotlight has been on the many ambitious infrastructure projects happening across the region. In the Philippines, President Duterte’s “Build!, Build!, Build!” infrastructure plan is underway with 75 different projects estimated to cost the country US$180 billion. In Indonesia, a high-speed rail system covering a distance of 140 kilometres connecting Jakarta to Bandung is also currently underway. Malaysia and Singapore are working on a high-speed rail project that would reduce commute times between the two nations. Consequently, if all these infrastructure mega-projects are completed in the coming decade, the Southeast Asia we know could be transformed into a bloc of developed nations.

Even with the massive infrastructure projects slated for the region, infrastructure demand is still expected to rise.

According to PwC’s report on ASEAN infrastructure opportunities, driving this demand for infrastructure is the region’s growing economy. Southeast Asia has been growing rapidly in the past five years. The region’s combined gross domestic product (GDP) is US$2.4 trillion and is expected to increase further in the future. As it stands, Southeast Asia is the seventh-largest economy in the world and is forecasted to jump to fourth by 2050.

The EU-ASEAN Business Council paper on infrastructure finance in ASEAN released earlier this year points out that demand for infrastructure is cyclic in nature. Economic growth leads to increased infrastructure demand, and improved infrastructure leads to more economic growth.

The paper highlighted the fact that infrastructure demand in the region is forecasted to grow further as 60 million new people enter the ASEAN workforce. In addition to that, mass urbanization will also take place with 90 million people predicted to migrate to urban areas between 2015 to 2030.

As infrastructure demand is expected to increase exponentially, governments and institutions in these countries need to prepare a roadmap on how to finance it. In a report by the Asian Development Bank (ADB) titled “Meeting Asia’s Infrastructure Needs”, it is expected that ASEAN nations will require around US$3 trillion in infrastructure investment between 2016 and 2030.

Funding the demand

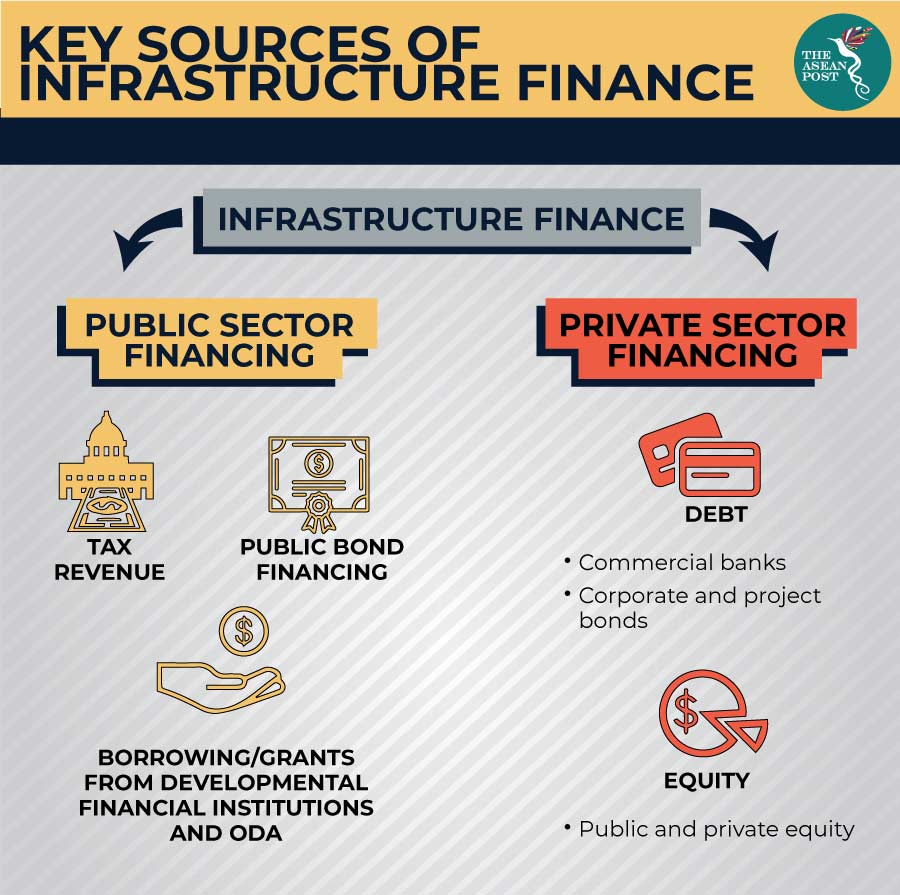

The problem therein lies in financing. The ADB has highlighted the fact that even if reforms were to be carried out by governments in the region with regards to public finances, the public sector could only cover about 50 percent of the total investment. Most recently, the Philippines reformed its tax laws to fund President Rodrigo Duterte’s infrastructure projects. However, these new tax reforms would only add 0.7 percent to the Philippines’ GDP.

This difference in required infrastructure spending and actual investment spending has been termed as the “infrastructure gap”. According to recent ADB data, total infrastructure spending in Southeast Asia was US$55 billion, while the estimated required annual spending for infrastructure in the region is US$157 billion. Therefore, Southeast Asia is currently facing an infrastructure gap of US$102 billion.

The EU-ASEAN Business Council has recommended that ASEAN member states engage more with private firms to finance its infrastructure projects. In the aforementioned paper from the EU-ASEAN Business Summit, the Council made several suggestions on how to improve investment conditions in the region.

One suggestion is to include deregulation in the investment sector to create suitable conditions for potential investors. In the paper, the importance of insurance companies and pension funds in providing long-term investment was also pointed out. However, various regulations have made it difficult for such investment vehicles to participate.

Another suggestion is to strengthen public-private partnerships (PPPs). PPPs are usually complex with investors and public institutions needing to work out guarantees and assurances over various factors such as costs, public policy and rules and regulations. To prevent any mishaps and complications, the EU-ASEAN Business Council recommends that governments put in place PPP laws and implement transparent bidding and contracting models.

The reality is that ASEAN needs infrastructure development if it wants economic growth. However, it also needs to be cautious when seeking partnerships with private firms. While private firms may help to bridge the infrastructure gap, it needs to be reminded that their involvement in infrastructure projects is largely driven by profit and monetary gain. Therefore, it is important that the governments of ASEAN member states don’t lose sight of the needs and interests of their nations and peoples when entering into PPPs.