The richest one percent in Thailand controls 58 percent of the country’s wealth and the top 10 percent earned 35 times more than the bottom 10 percent. In Indonesia, the four richest men there have more wealth than the poorest 100 million people, and about 50 percent of the country’s wealth is in the hands of the top one percent. In Vietnam, 210 of the country’s super-rich earn more than enough in a year to lift 3.2 million people out of poverty. The country’s richest man earns more in a day than the poorest person earns in 10 years. In Malaysia, while only 0.6 percent of its 31 million people are living under the poverty line, 34 percent of the country’s indigenous people and seven percent of children in urban low-cost housing projects live in poverty. In the Philippines, the average annual family income of the top 10 percent is estimated at US$14,708 in 2015, nine times more than the lowest 10 percent at US$1,609.

This is the uncomfortable truth about Southeast Asia, home to some of the world’s fastest expanding economies, with a combined economy of US$2.6 trillion or about the size of the United Kingdom’s (UK's) economy. The widening gap between the ‘haves’ and the ‘have nots’ is reflected in the progress reporting of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) achievements up to 2017.

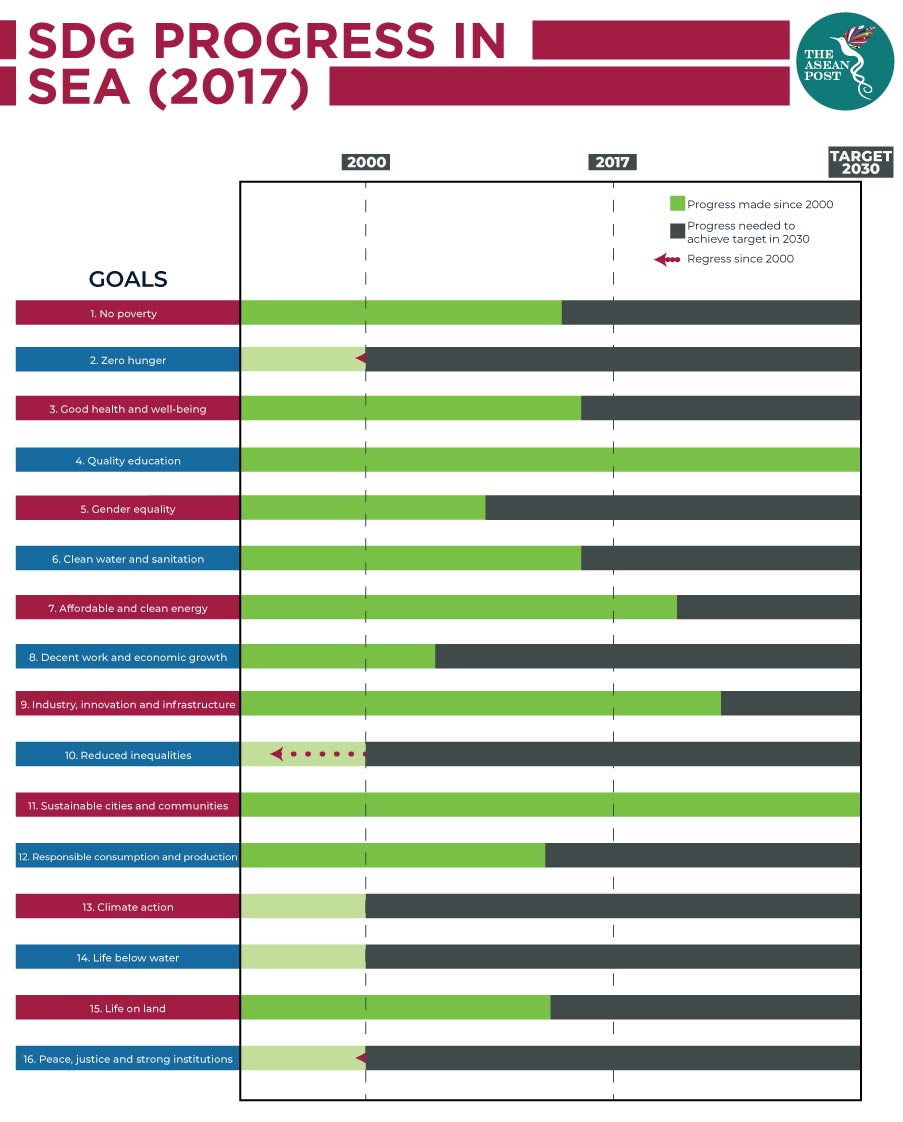

According to the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (UNESCAP) report, the Southeast Asian subregion has not been successful in its efforts to reduce inequalities. In fact, the region is the only subregion within Asia Pacific with widening inequalities. Southeast Asia is also the only subregion for which the situation is worsening for Goal 2 targeting zero hunger, food security, improved nutrition and sustainable agriculture.

“Southeast Asia is the subregion which has made the most progress towards achieving Goal 9 focused on industry, innovation and infrastructure. It has also made some progress towards Goal 8 focused on decent work and economic growth. Yet Southeast Asia has seen inequalities widen, a setback to overcome if Goal 10 (Reduce inequality within and among countries) is achieved,” the report stated.

UNESCAP’s Executive Secretary, Shamshad Akhtar, said that wealth has become increasingly concentrated and inequalities have increased both, within and between countries.

“The Gini coefficient increased in four of our most populous countries, home to over 70 percent of the region’s population. Human, societal and economic costs are real. Had income inequality not increased over the past decade, close to 140 million more people could have been lifted out of poverty. More women would have had the opportunity to attend school and complete their secondary education. Access to healthcare, to basic sanitation or even bank accounts would have been denied to fewer citizens. Fewer people would have died from diseases caused by the fuels they cook with. Natural disasters would have wrought less havoc on the most vulnerable.

The uncomfortable truth is that inequality runs deep in many parts of Asia and the Pacific. There’s no silver bullet, no handy lever we can reach for to reduce it overnight. But an integrated, coordinated approach can over time return our economies and our societies to a sustainable footing,” he wrote.

The UNESCAP publication also reported on Southeast Asia’s struggle in reducing suicide mortality, reducing road traffic deaths, widening access to safely managed drinking water, improving employment in the manufacturing sector and improving oceans’ health. Southeast Asian countries also face their biggest struggle when it comes to loss of natural forests. The subregion has made no progress towards achieving SDGs on climate action and life below water.

But it is not all gloomy for ASEAN bloc countries. Southeast Asia, as a sub region, is on track to achieve 20 out of the 53 targets. Its progress is good for Goal 4: Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all; Goal 7: Ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy for all; Goal 9: Build resilient infrastructure, promote inclusive and sustainable industrialization and foster innovation; and Goal 11: Make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable. Southeast Asia’s progress is the best in the Asia Pacific sub regions for all these goals. Southeast Asia has also achieved the level of quality education targeted for 2030 under the SDG.

Left unchecked, inequality will not only have negative consequences on economic growth, but it could also lead to political and social issues. Inequality, compounded by food insecurity, loss of natural capital such as biodiversity and ecosystem services from the forest and marine ecosystems, as well as unaddressed climate concerns and impacts, could put ASEAN’s future growth at risk. Therefore, regional and national policy makers should revisit their priorities and work together to prevent the current trend from continuing.