Tioman Island on the east coast of Malaysia first appeared on the world’s radar after its beaches were depicted in the 1958 movie South Pacific as ‘Bali Hai’. In the 1970s, the island was named by Time magazine as one of the world’s most beautiful islands. Since then, the island’s tourism industry has grown by leaps and bounds. Like many other small islands, the dwellers there have always faced a water shortage. However, with the expansion of its tourism industry, the situation has been amplified.

Compounding the problem is the fact that September and October, the driest months on the island, is also the peak tourist season, setting the scene for water conflict between tourists and the locals. Tourists may complain about a lack of water on their holidays but for the 3,200 hardest hit residents of Kampung Salang, Air Batang, Tekek, Genting, Mukut, Lanting, Nipah and Juara, the idea of promoting their island as an ecotourism destination is bewildering as even something as basic as water supply is not made available to them.

In Bali, Indonesia, the tourism-induced water crisis is on an even larger scale. Tourism contributes toward 80 percent of Bali's economy and about 85 percent of it is in the hands of non-Balinese investors. It has been quoted that as much as 65 percent of the island's groundwater is poured into the tourism industry, drying up 260 out of more than 400 Balinese rivers. Groundwater over-extraction has lowered the island's water table by some 60 percent, risking irreversible saltwater intrusion.

The tourism industry is a substantial tool for socio-economic development for an area or country, representing 10 percent of the world’s gross domestic product (GDP), 30 percent of services exports, and providing one out of every 10 jobs globally. As an industry, tourism is interlinked with virtually all other economic sectors, offering ample opportunities for women, youth, rural, and indigenous communities. However, over-consumption of such a scarce and important resource like water by the tourism industry which is known for its extravagance is a valid concern.

According to the United Nations World Tourism Organisation (UNWTO) in its ‘Tourism for Development’ report released earlier this year, while the sector accounts for a small share of global water use, tourism can place a great strain on freshwater resources in areas where water scarcity exists - both in developing economies, such as Bali, Indonesia, and in industrialised countries, such as Spain.

“Levels of water use vary considerably between types of facility - from 100 to 2,000 litres per guest, per night. These are often far higher than the quantities of water used by local populations. Water tends to be undervalued relative to its true environmental cost. Water costs are increasing while expectations for more sustainable water use by the tourism sector are growing.

“The EarthCheck Research Institute has reported that large disparities are likely to result from the extensive use of water by accommodation providers - for example in landscaping, pools and other water features within tourism establishments - when compared with very constrained domestic water usage by locals. Such imbalances raise serious concerns about water equity and the ethics surrounding water access,” the report stated.

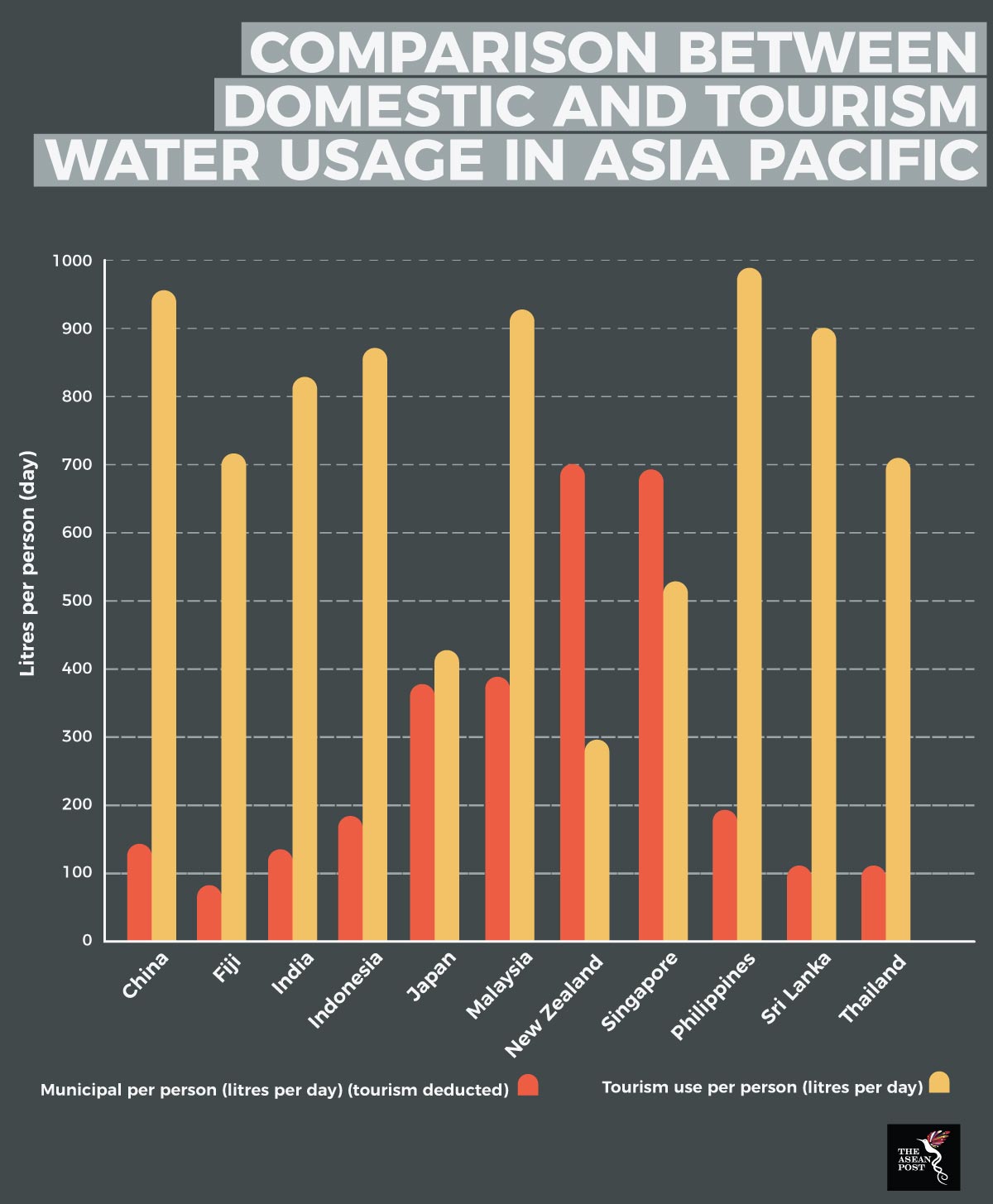

The EarthCheck Research Institute undertook a water equity analysis to develop a clearer picture of tourism’s water use in relation to domestic water use by local populations. The analysis found that the Philippines, China and Malaysia are at the top of the list in terms of the average amount of water used by each hotel guest per night stay at 981 litres/guest-night, 956 litres/guest-night and 914 litres/guest-night, respectively. The study confirms disparities in water use between tourists in hotels and the local population, typically in the order of a factor of three to eight times. For example, in Thailand, the Philippines and Indonesia, daily water use by tourists exceeds that of locals by a factor of around five to 6.5.

Source: Water equity - Contrasting tourism water use with that of the local community (Becken, S.)

With expanding populations, increased competing uses, and a growing tourism industry, more and more tourist destinations will be suffering from water stress. This will be further exacerbated by climate change. Consequently, the tourism industry and its players need to acknowledge their disproportionate use of water resources.

The needs of tourists who are at holiday destinations temporarily should not supersede those of the locals who live there. Particularly in areas where water is scarce, strict impact assessments on water resources need to be undertaken, followed by careful planning and effective management of water consumption. Tourism is not just about visiting a specific geographical location, it is also about the people, culture and environment. Responsible tourism should be a win-win situation for all parties involved.