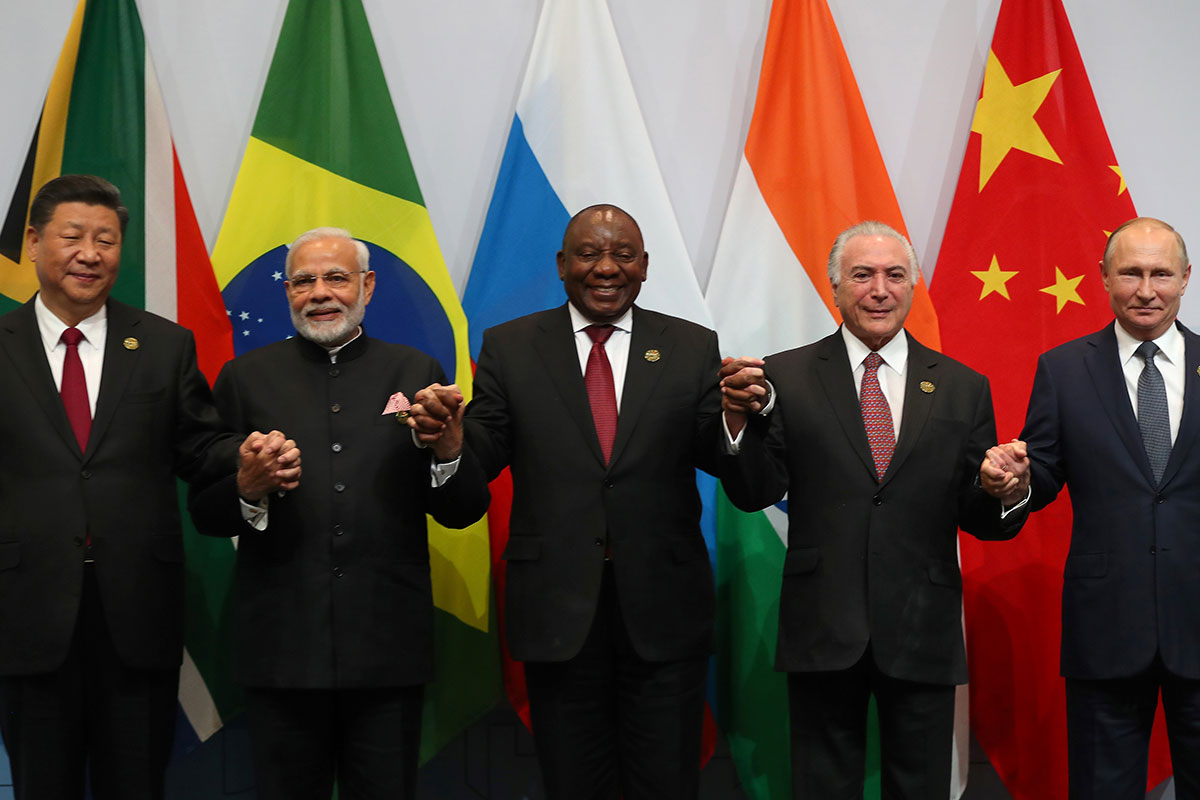

This week, South Africa is hosting the tenth annual gathering of the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa). When the first BRIC summit was held in 2009 (South Africa was added in 2010), the world was in the throes of a financial crisis of the developed world’s making, and the increasingly dynamic BRIC bloc represented the future. By coming together, these countries had the potential to provide a geopolitical counterweight to the West.

But Western commentators have long underestimated that potential, forcing the BRICS to demand greater representation in global-governance institutions. In 2011 and 2012, the BRICS challenged the process of selecting leaders at the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank. But, lacking a united front behind them, a European (Christine Lagarde) and an American (Jim Yong Kim) continued to preside over those organizations. And though the BRICS did get these institutions to reform their voting structures to give developing countries greater weight, the United States (US) and Europe still wield disproportionate power.

Against this backdrop, the BRICS took it upon themselves to pursue “outside options,” by establishing the New Development Bank (NDB) and the Contingent Reserve Arrangement in 2014. These initiatives have been presented as complements to the prevailing Bretton Woods system, but it is easy to see how they could also form the foundation for an alternative global-governance framework at some point in the future.

After all, while the BRICS still emphasize the importance of multilateralism, it is clear that they are not wedded to the current international order. Yes, permanent membership of the United Nations (UN) Security Council gives China and Russia distinct advantages over most other countries. But both are nevertheless sceptical of the existing order.

China’s foreign policy has increasingly come to reflect its status as a rising superpower. In accordance with President Xi Jinping’s “Chinese Dream,” China has been pushing hard for a relationship of equals vis-à-vis the US. And at the 19th National Congress of the Communist Party of China last year, Xi made his goal of restoring China’s great-power status even more explicit.

How China uses the many geopolitical instruments at its disposal will matter a great deal to the other BRICS countries, because they will have to adapt their national strategies to China’s own “outside options.” Since 2013, China has established the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), launched the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), and proposed expanding the BRICS into a “BRICS Plus” – with China presumably at its head.

China announced its plans for the AIIB shortly after signing the NDB articles of agreement in 2014. In the case of the NDB, each of the BRICS owns an equal share, and each contributed US$10 billion to the initial subscribed capital. Although equitable shareholding was not China’s preferred route, it did not force the matter.

By contrast, China is the AIIB’s largest shareholder by a wide margin, holding a 26.6 percent stake, compared to India’s 7.7 percent and Russia’s six percent. Brazil and South Africa, meanwhile, have made no capital contributions to date, despite being designated as “founding members.” The AIIB thus exemplifies China – not the BRICS – exercising its own “outside option.” The institution is open to developing and developed countries alike, and China is at its centre.

Similarly, since its launch in 2013, the BRI has evolved into what Cobus van Staden of the South African Institute of International Affairs calls a decidedly “Beijing-centric global trade and investment order.” The BRI is Xi’s signature project. His hope is to create a “community of shared destiny” not only across Eurasia and the Indian Ocean. As a practical matter, the BRI allows China to translate its economic might into geopolitical power.

Lastly, the proposal for a “BRICS Plus” signals a shift in China’s external relations – one that will obviously affect the other BRICS. At the 2017 BRICS summit in Xiamen, China, Xi indicated that he wants the group to represent something larger than its current members, given the premium that it already places on cooperation among developing countries. Xi’s initial proposal seemed to imply an expansion of the group, which some of the other BRICS have staunchly resisted. Still, South Africa is now taking the idea forward, by holding a “BRICS Plus” meeting on the third day of this year’s summit.

These three developments underscore the extent to which an emboldened China now wields outsize power relative to its BRICS partners. Through the AIIB and the BRI, China is laying the foundation for a new regional and global order. The Chinese government is actively executing Xi’s vision through trade, investment, and the strategic projection of power, particularly in the South China Sea.

Nevertheless, the other BRICS have an important role to play in legitimating China’s “other options.” Each is committed to reforming the international system, and to building a more multipolar world; but they have not necessarily reached a consensus about what a new order should look like.

Under President Cyril Ramaphosa, South Africa is once again asserting leadership on the African continent. This could entail a greater focus on Africa within the BRICS. But as South Africa pursues the continent’s interests in addition to its own, it will have to remain open to working not just with the BRICS, but also with other developing countries and coalitions. The ultimate goal must be to support and reinforce a rules-based order. After all, that is in Africa’s interests.

Elizabeth Sidiropoulos is Chief Executive of the South African Institute of International Affairs.