Cambodia’s plans to boost its cassava industry has hit a snag with an outbreak of the mosaic virus. Thailand, a main importer of Cambodia’s cassava issued a warning in June that it may ban the produce if necessary.

The virus has not appeared in Thailand before and officials there fear an outbreak will lead to substantial losses to the nation’s agriculture sector and cassava industry. It is the world’s largest exporter of tapioca products, making up over 50 percent of the global market share. It supplements its homegrown cassava with imports from nations such as Cambodia and Lao PDR.

The Sri Lanka cassava mosaic virus, previously found in India and Sri Lanka, mottles the leaves and eventually kills the plant.

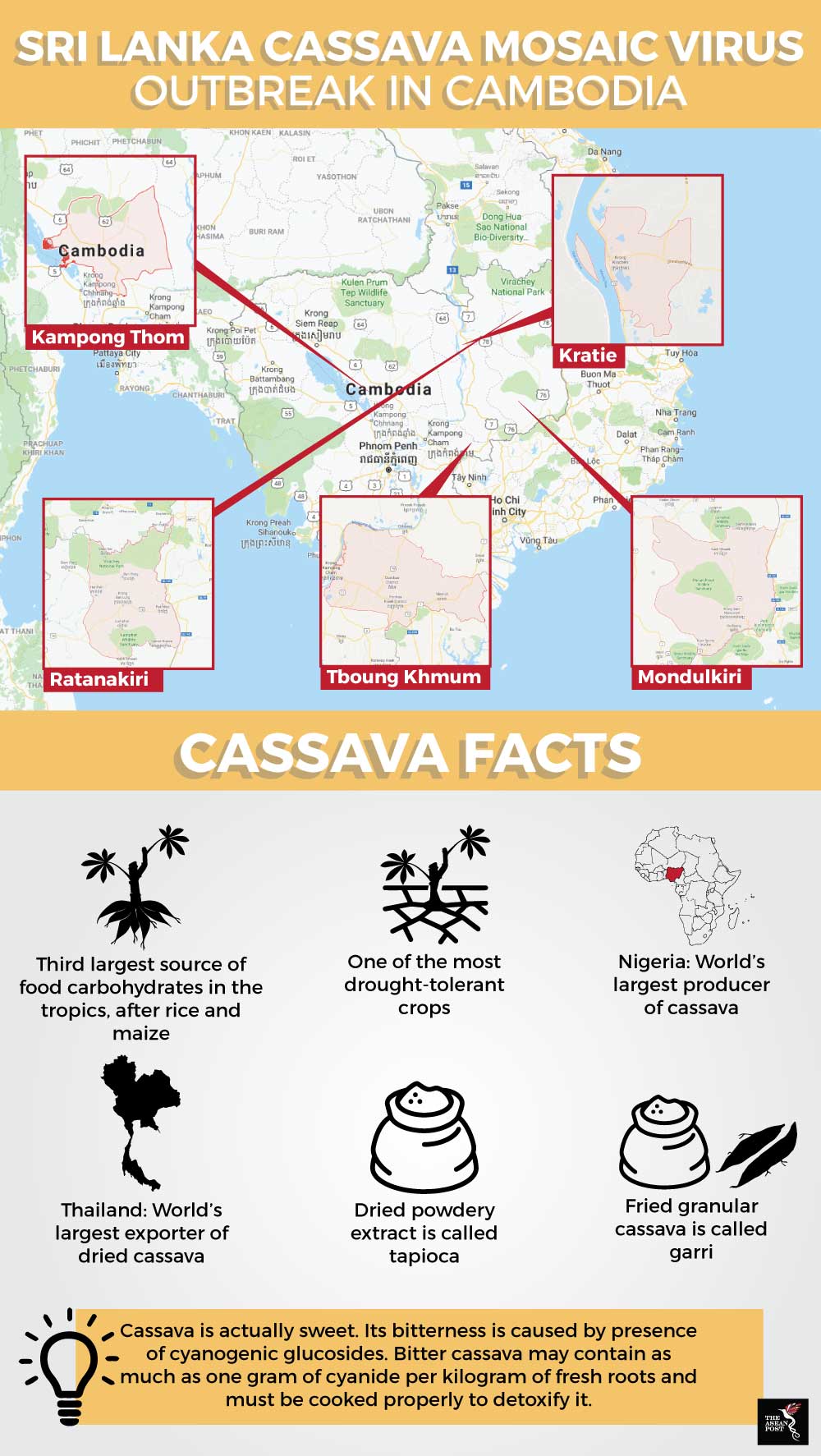

The Cambodian government rejected claims of any outbreaks in its shared border with Thailand, although in September, it admitted the virus was found elsewhere in the country. The first incident was reported in Ratanakiri in 2015. Despite the authorities’ efforts to ban the movement of cassava seeds to other provinces, it has since spread to Mondulkiri, Kratie, Tboung Khmum and Kampong Thom.

“Fortunately, there is no indication it has reached the western provinces,” said Hean Vanhan, director of the General Department of Agriculture in Cambodia’s Ministry of Agriculture.

The director of the Department of Agriculture in Kratie, Kuy Huot, was reported as saying only a small number of farms in the southern province were attacked by the virus. It was contained by educating the farmers on the subject. The department is also encouraging the use of resistant strains and crop rotation.

Thai concerns

Thailand’s threat to ban Cambodia’s cassava appears unnecessary as the Thai Tapioca Development Institute, an agriculture research centre, has developed a cassava seed immune to the virus. However, this would require clearing contaminated plantations for replanting, which affects the livelihood of the farmers.

“If this happens, we will try to provide financial assistance so that they can buy new seeds,” said Vanhan.

Local company Amru Rice said it is already using virus-resistant seeds imported from Thailand. “As we comply with all regulations for growing organic cassava, we have not encountered any issues,” said Song Saran, CEO of Amru Rice.

Amru Rice has a contract farming scheme with 10 agricultural communities in Preah Vihear, Kratie and Kampong Thom. A total of 700 farmers with a combined total of 2,000 hectares of land, produce organic cassava for Amru Rice and earn 20 percent more than the market price.

Source: Various sources

Source: Various sources

According to the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), Cassava is the most important upland crop in Cambodia. It is also the country’s second largest agricultural crop after rice.

In 2016, cassava was cultivated in over 684,070 hectares, yielding 14.8 million tonnes a year. As the country lacked processing facilities, about 90 percent of the harvests is exported to Thailand and Vietnam. This also made farmers vulnerable to price fluctuations, often leading them to lament that it is an unprofitable crop.

Changes coming

That may change soon with the entry of Hong Kong-listed Green Leader (Cambodia). It signed a memorandum of understanding in April with the UNDP to develop the country’s cassava industry.

UNDP country director Nick Beresford lauded Green Leader as a “private catalyst to a new phase in which more value is generated for the cassava industry, redistributing value-added downwards to different actors and towards the end of the value chain.”

Green Leader’s CEO, Michael Tse said the company will build 20 processing factories in Cambodia over the next five years. Construction of its first starch processing plant began in April in Snoul, Kratie. Like Amru Rice, Green Leader will also engage the local farmers through contract farming, providing them with seeds and resources.

The Cambodian government is preparing a National Cassava Sector Policy aimed at making the kingdom a major global supplier of cassava-based products. Its three main strategic objectives are to transform the crop from subsistence to commercial production; to attract investment in cassava-processing and value-added products; and to become more competitive by turning market access into market presence, improving trade facilitation and reducing trade-related costs.

“The National Policy, once enacted, will address the challenges faced, enhance efficiency and expand the value-chain, offering a win for the economy and those employed in its cultivation and allied activities,” said Dr Richard Marshall, country economist, UNDP-Cambodia.

The International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT) ranks Cambodia as the world’s eighth largest cassava producer and the fourth largest in Southeast Asia.