The Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) will be unveiling its results for 2018 sometime next year. When it does, one of the Association for Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) countries that will come into focus is Indonesia.

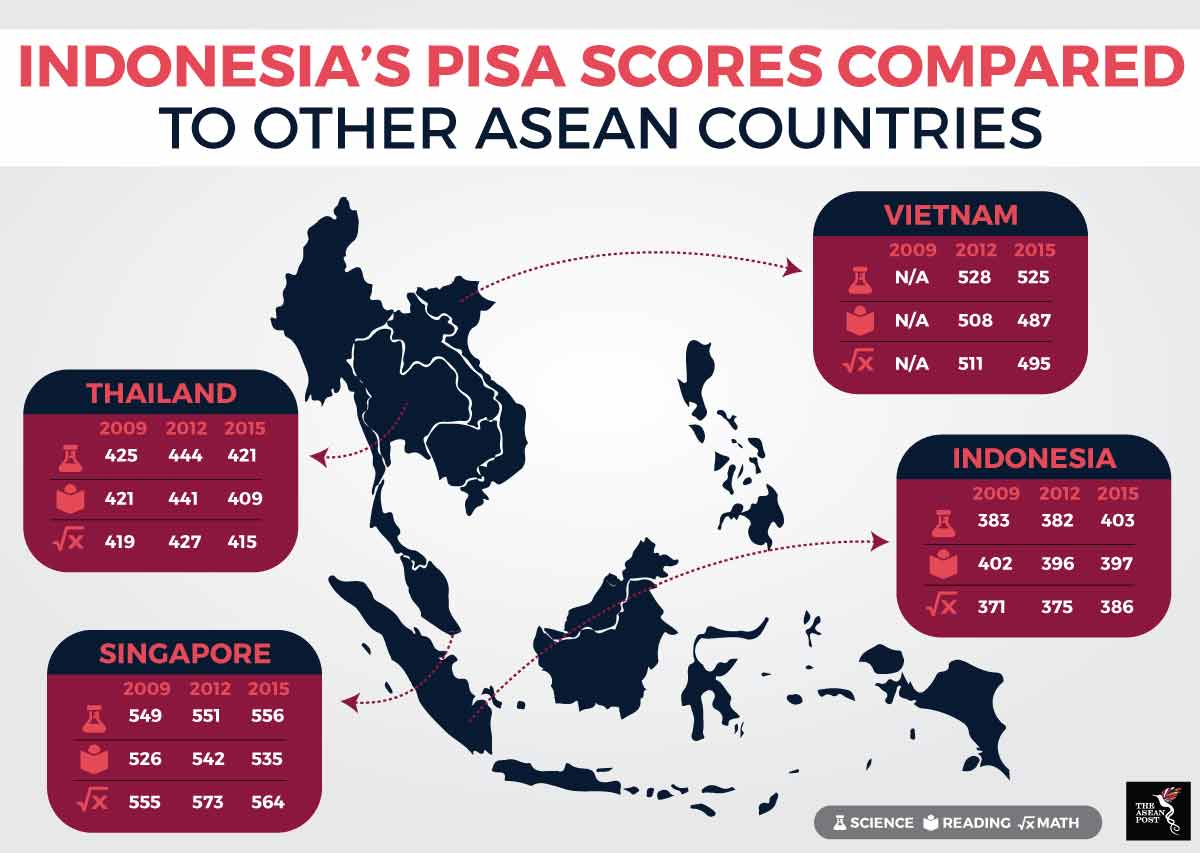

In the PISA results for 2015, Indonesia fared poorly in math, reading, and science compared to all the other ASEAN member states involved in the study. For math, Indonesia managed to score 386 points, for reading, the country scored 397 points, and for science, Indonesia only scored 403 points.

From the 70 countries reviewed in 2015, Indonesia was ranked at 62nd. This, however, is still an improvement compared to its ranking of 63 out of 65 countries in the PISA 2012 results.

In comparison with some other ASEAN countries, Singapore ranked 1st in 2015 and 2nd in 2012. Thailand ranked 55th in 2015 and 48th in 2012.

Source: The Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA)

So why is Indonesia trailing behind? A recent report entitled “Beyond access: Making Indonesia’s education system work” from the Sydney-based Lowy Institute found that one of the main problems with Indonesia’s education system stemmed from “politics and power”. The report claims that there is little incentive for old elites to drastically overhaul the education system, arguing that they would rather exploit it to “accumulate resources, distribute patronage, mobilise political support, and exercise political control.”

According to the Lowy Institute, problems which have stemmed from this lack of political will include corruption, poor quality of teaching and staff absenteeism.

The United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) Indonesia says that in rural and remote parts of Indonesia, early childhood development services are either absent, inaccessible or unaffordable to most children, meaning they miss out on valuable early learning and development opportunities that their urban counterparts receive.

As if this wasn’t a big enough issue on its own, UNICEF Indonesia also pointed out that the country is situated in one of the world’s most active disaster hotspots with disasters ranging from tsunamis, earthquakes and volcanic eruptions to landslides, floods, droughts and forest fires. “Of 34 provinces in Indonesia, 30 are in high risk and four are in medium risk zones. Most disasters affect schools. During the period of 2014-2016, major disasters affected more than 31,000 schools in Indonesia,” UNICEF Indonesia reported.

Just recently, Indonesia's National Disaster Management Authority said more than 600 educational facilities have been damaged on Lombok as the result of a series of tremors between 29 July and 9 August. The Indonesian Education Ministry said this figure included 341 primary schools and 124 preschools. Lombok is home to more than 3.3 million people including thousands of school-going children.

Efforts on the education front

There have been efforts by the Indonesian government to combat the country’s education challenges. On 23 July, Indonesia’s Minister of Education and Culture Professor Muhadjir Effendy held a bilateral meeting with Vietnam’s Minister of Education and Training Professor Phung Xuan Nha at the Vietnamese Education Ministry in Hanoi.

The bilateral meeting reaffirmed the commitment of the two countries to continue the implementation of a memorandum of understanding (MoU) on education cooperation signed on 23 August, 2017. The hope is that out of these meetings, cooperation between the two countries in terms of education will be strengthened, especially in vocational training and teachers’ capacity building.

Recently, Indonesia’s Research, Technology and Higher Education Ministry subscribed to a database of scientific e-journals which can be accessed by researchers, university lecturers, students and non-ministerial government agencies for free. The subscription, which costs 14.8 billion rupiah (US$1 million) for this year alone, will hopefully help Indonesian academics produce original scientific research and journals.

Whether efforts by the Indonesian government to improve the state of education in the country will be fruitful or not is yet to be seen but hopes are running high as the countdown begins for the 2018 PISA survey. It’s more than likely that many Indonesians are hoping that their country will be able to bump up its ranking by a few notches at least.