For many Javanese Indonesians, bird-keeping is in their DNA. A long-held tradition, the popular pastime has spread beyond Java as natives of the island were relocated to less densely populated islands in the country under the Indonesian government’s transmigration program. In urban centres on Java and Sumatra, the trading of caged-birds is rampant, with a report estimating an average of 614,180 native songbirds trapped and traded annually throughout the two islands.

Besides the “peace of mind” and relaxation songbirds bring to their owners with their rich and melodic voices, bird keeping also signifies status and offers financial gain for the keepers through the many organised singing contests. An avid collector of songbirds, President Joko Widodo, earlier this year, offered more than US$40,000 to buy a prize-winning bird from its owner.

In July, for the first time in almost 20 years, the Indonesian government expanded its list of wildlife species banned from trading and hunting. This new list revises the appendix of a 1999 regulation listing plant and animal species endemic to the country that have small populations in the wild and are on the decline because of overhunting and habitat loss. The list also struck off species whose populations are recovering or which are already extinct.

The birdkeepers’ uprising

Bird species make up most of the newly added 242 protected species, bringing the nationally protected species number up to 919 from 677. This includes species typically caught and caged for the songbird trade. Overnight, the released list sparked concerns that thousands of bird owners would be vulnerable to penalties, despite the ministry’s statement that it would not be enforcing the new list immediately. Under the Indonesian 1990 law on natural resources and ecosystem conservation, persons convicted of trading or keeping protected flora and fauna can face up to five years in prison or be fined up to US$6,724.

The release of the new list triggered protestations by owners of songbirds from all over the country, with some coalitions demonstrating outside the Ministry of Environment and Forestry in Central Jakarta. Their argument: the ban on buying and selling commonly traded songbirds lacks scientific and cultural bases, with several species included on the list currently being bred on a large scale and far from being endangered.

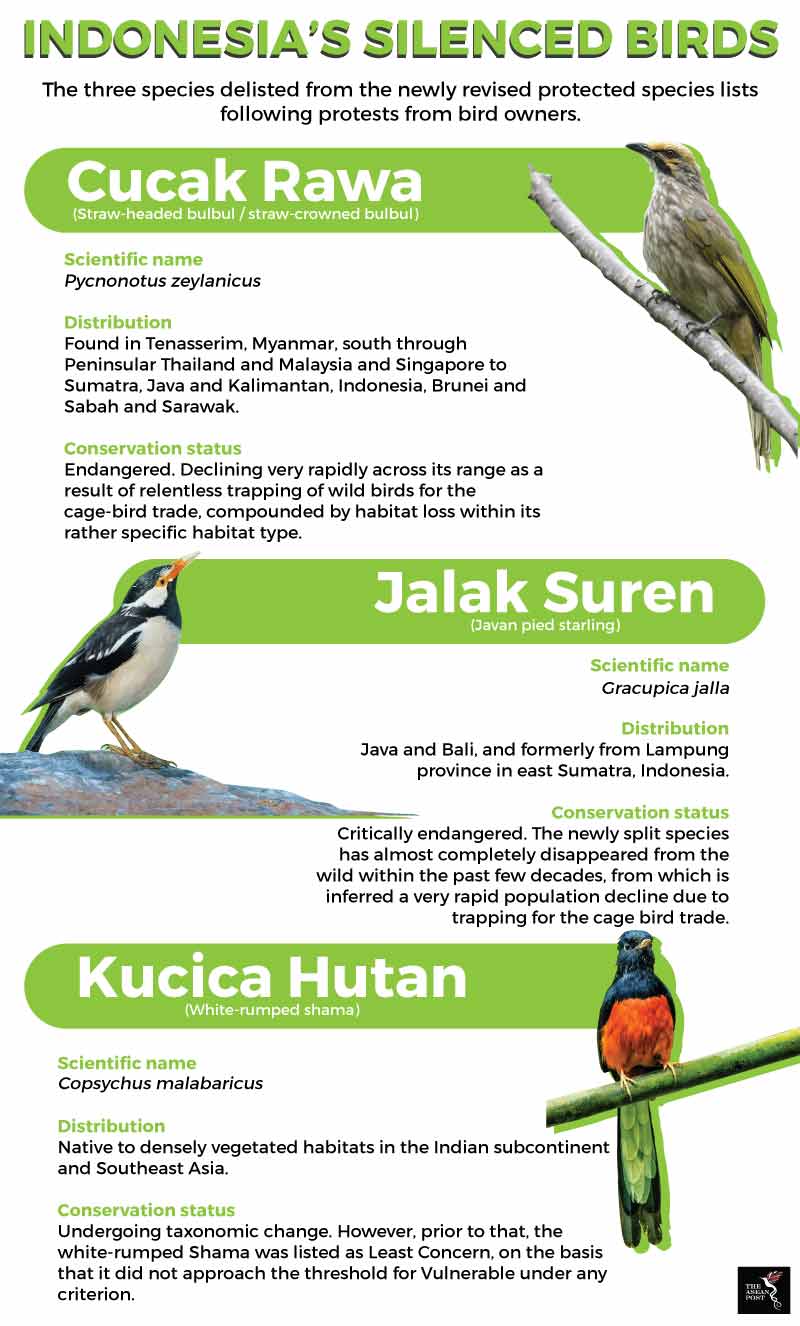

Within weeks, the Indonesian Environment and Forestry Ministry removed three popular songbirds - kucica hutan (white-rumped shama), cucak rawa (straw-headed bulbul) and jalak suren (Javan pied starling) - from the newly revised protected species list due to pressure from bird-keeping communities. The first two delisted bird species are categorised by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) as endangered and critically endangered species, respectively. According to the ministry’s Biodiversity Conservation Director, Indra Exploitasia, the delisting is based on a social and economic study conducted by her office following the protests.

Source: IUCN and BirdLife International.

The voice of silenced birds

While populating cages in homes, the trading of songbirds has gradually silenced the song of these magnificent birds in forests. An assessment of the trading of black-winged mynahs or Achridotheres melanopterus by Vincent Nijman, an anthropology professor at Oxford Brookes University, England, found that while some of the birds were bred in captivity, many were harvested from the forest as it was cheaper than breeding. Nijman, who studies the interactions between humans and wildlife, said that after visiting and observing bird markets in Indonesia for over 25 years, he noticed that as mynahs became more common in these markets, they grew ever scarcer in the forests.

“It became very clear that the decline was at least in part due to trade,” Nijman was quoted as saying to National Geographic.

As Indonesia nears its general election, the voice of bird owners seems loud and vital. For bird owners, the listing of their beloved pets as nationally protected species may seem like an infringement on their right to an inherited tradition handed down through the generations, and giving them their identity.

But for the delisted songbird species, this could have been their last chance for survival. Without the protection of the government, these endangered species could now hurtle towards extinction.

Related articles:

Saving Vietnam’s bile farming bears