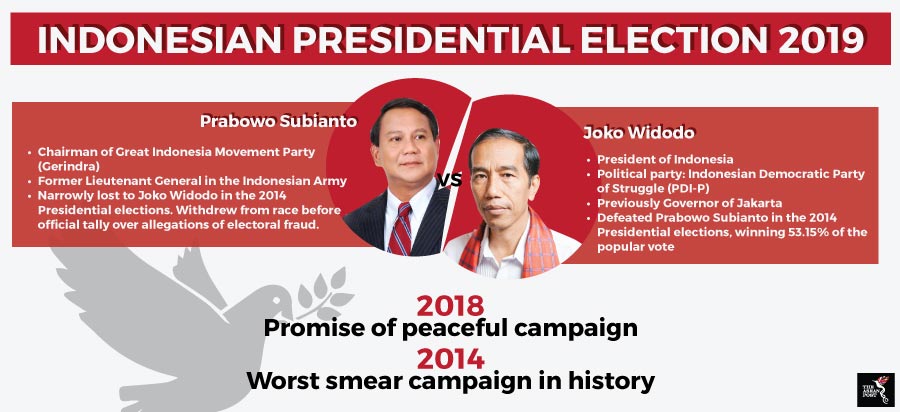

Indonesia’s presidential election was officially kicked-off with the two contenders - Joko “Jokowi” Widodo and Prabowo Subianto - releasing white doves and vowing a peaceful campaign period. Hopes are running high that the promise of peace that comes with this gesture continues during the months leading up to polling day in April next year. But if the 2014 election was anything to go by, then Indonesia will need to brace itself for a turbulent flight.

The campaigning period prior to the 2014 presidential election was a number of things, but peaceful was not one of them. While Jokowi and Subianto did not publicly attack each other, this did not stop the campaign period from being tainted with dirty campaigning and wild internet rumours particularly against Jokowi, whom several political pundits at the time had touted as the favourite. This was because of his relatively clean record and lack of direct association with the Indonesian political establishment.

Indikator Politik Indonesia’s opinion polls had placed Jokowi as the frontrunner in terms of popularity with 55.7 percent of respondents favouring him over Subianto in March 2014. This percentage, however, dwindled to 31.8 percent in April. Some analysts believe this had to do with the smear campaign initiated against Jokowi.

Later, in July 2014, a survey by Roy Morgan Research, Australia's foremost market research company, found that long-time favourite Jokowi was leading Subianto by a slender four percentage points only. The company’s face-to-face interviews with 3,117 voters in June 2014 in all 34 provinces put Widodo at 52 percent against Subianto’s 48.

People’s Torch

While smear tactics were commonplace during election campaigning prior to 2014, local and foreign observers had agreed that the intensity and persistence of attacks on Jokowi during the 2014 campaign period were unlike anything Indonesians had witnessed before.

Social media and tabloid papers were abuzz with rumours and allegations against the man once dubbed as “Indonesia’s Obama”. Allegations included claims like Jokowi’s mother was an activist with the banned Indonesian Communist Party. Some groups like the Forum of Islamic Society (Forum Ummat Islam) even went as far as saying that it was forbidden for Muslims to vote for Jokowi.

The largest smear campaign came from a tabloid aimed at discrediting Jokowi and was circulated among Islamic boarding schools in Java. People's Torch (Obor Rakyat) described Jokowi as a non-Muslim of Chinese descent, corrupt and just a "puppet candidate" of former President Megawati Sukarnoputri. It also portrayed him as a liar with a long nose like Pinocchio and of being a Singapore citizen.

The third edition of the tabloid prompted police to open a libel investigation and question the editor-in-chief, who was a staff assistant at the office of then President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono. The ruling Democratic Party which said it was neutral earlier in the campaign threw its support behind Subianto just two weeks before the 9 July election.

Undoubtedly, such allegations would have tugged on the heartstrings of at least some of the citizens of the world’s most populous Muslim nation.

Source: Various sources

Tying the camel

Islam plays a vital role in the lives of many Indonesians and the country boasts the largest Muslim population in the world. According to Pew Research Center, 88 percent of Indonesia’s population or 238.8 million is expected to be Muslim by 2030. Among ASEAN states, Indonesia has the largest Muslim population followed by Malaysia with 64.5 percent or 22.7 million Muslims.

Perhaps learning from previous experience, Jokowi has ensured that his opponent will not be able to tarnish his reputation as a Muslim. On 9 August, Jokowi announced 75-year-old conservative Muslim cleric Ma’ruf Amin as his running mate in the upcoming presidential elections. Amin is the supreme leader of Nadhlatul Ulama, the largest Muslim organisation in the country. Subianto has selected Sandiaga Uno, a moderate and deputy governor of Jakarta, as his choice for vice president.

Norshahril Saat, a Fellow at the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute in Singapore, noted recently that Jokowi knows the importance of winning the hearts of conservative Muslim Indonesians.

“Jokowi is aware how by not managing conservative Muslim sentiments, as witnessed during the Action for Defending Islam (Aksi Bela Islam) protests of 2016 against former Jakarta governor Basuki Tjahaja Purnama (Ahok), will be politically costly for him,” she said.

Religion is probably the most effective weapon one could use to run a smear campaign in Indonesia. Islam continues to play a very big role in politics as evidenced by Ahok’s loss to Anies Baswedan in the Jakarta Governor race and his (Ahok’s) subsequent imprisonment in 2016 for allegedly insulting the Quran.

Jokowi is well aware of this and has arguably solidified his position with conservative Muslims in Indonesia with his appointment of cleric Ma’ruf Amin; leaving Subianto with nothing much to go on. Therefore, it is likely the campaign period will not be as dirty as it was in 2014 unless Jokowi takes a page from Subianto’s playbook and runs a smear campaign of his own.

Related articles:

Why did Jokowi pick cleric Ma’ruf Amin?